There are three key pieces of information every gardener needs to know before they start their garden seeds indoors. We’re talking garden seeds for growing transplants -- plants that you will grow with the intention of planting them outside this spring when the time is right.

Armed with these two pieces of information, you can make the right decision about when to start which types of plants. It will help you plan the timing of your garden and planting later on, too.

Jump to:

1. Plant Hardiness, Growing Zone, or Hardiness Zone

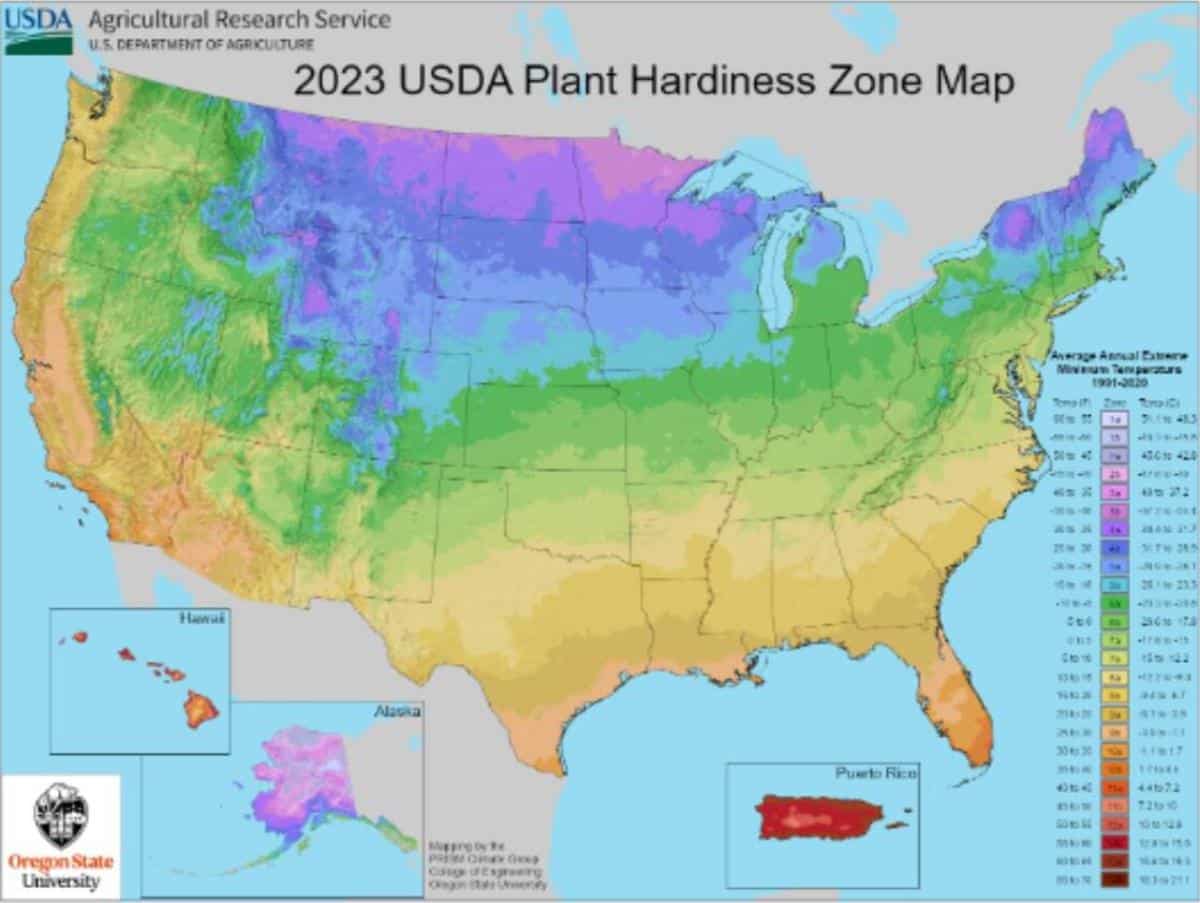

First, you’ll want to know your plant's hardiness zone, often referred to as just the “hardiness zone.” Many countries have a system of numbering or labeling hardiness zones. Probably the most well known is the USDA plant hardiness zone map. But there are others.

Why do you need to know your hardiness zone before you start seeds for transplanting?

The reason to know your plant hardiness zone is for planting perennial plants. Hardiness zones are designed to determine if a plant can survive your average winter temperatures. They are based on collected climate data, typically for a period of about a decade.

The plant(s) may be in its dormant state in the cold months, but your location should not see it killed by winter temperatures or winter conditions if you are choosing plants that can withstand your winter.

The bottom line: Know your hardiness zone so that you don’t waste time growing plants from seed that cannot survive where you live.

You can grow perennials from seed. That’s a good, cheap way to grow perennial plants for your yard and garden. But it's not worth starting perennial seeds that will die at the end of the garden season. At least, not if you were planning for them to be grown as perennials and reach their full perennial potential.

Ways gardeners hedge to beat hardiness zones

Sometimes, you can grow a plant in your area that is not rated for survival according to your hardiness zone, but you will need to grow it as an annual plant. This applies to many of the flowers we consider annuals, and most garden vegetable plants. We can use them and get used out of them for a season, but they can’t come back after the winter.

It may also be that you can grow a tender perennial where you live, but you will need to take steps to protect it if you want to grow that same plant again next season. This is what we do when we dig tender garden bulbs or tubers, when we bring plants indoors for the winter, or when we store a dormant plant inside until the spring.

Hardiness zone is for choosing what, not when

For planting, the hardiness zone has its place, but it is not so much in timing as it is in choosing appropriate plants. It mostly relates to planting perennials because we would not expect annuals to live through the winter in our location, anyway.

Keep in mind that there are edible perennial vegetables and plants, so a hardiness zone can apply to growing edible plants, too.

For example, many herbs are perennials in many locations. In others, you may have to grow more delicate herbs as annuals. But it’s worth exploring your hardiness zone to see what can be grown as a perennial herb garden plant.

Other edibles for which hardiness zone information would apply include berries and shrubs (raspberries, strawberries, blueberries, elderberries, currants, and so many others), and also perennials like rhubarb, asparagus, and more.

Using the hardiness zone or hardiness range will help you invest in the right plants and not waste time, energy, and money on plants that cannot survive in your location.

The zone has only a slight bearing on what annuals you should grow. That is dictated more by the length and timing of your growing season, which has more to do with your frost dates, which are discussed next.

Recent adjustments and finding hardiness zones for countries other than the U.S.

The USDA adjusted their hardiness zones recently, so if you have not checked yours in a while, you may want to take another look.

The United States is not the only country that assigns hardiness zones for growers. Canada, the UK, and several other countries assign zones, too. Do note, the zone numbers are not always the same from country to country.

So, Zone 5 in Canada may not be in the same temperature and climate range as Zone 5 in the US or the UK. Many of the same perennials can be grown in these countries, but you’ll need to adjust for the right climate assignment to decide what you can or cannot grow as a perennial there.

If you live in a place that does not have a system of assigned hardiness zones, you can easily figure out what zone is equivalent to your climate so you can cross-reference to find out if certain perennials are appropriate to grow where you live.

2. Last Frost Date

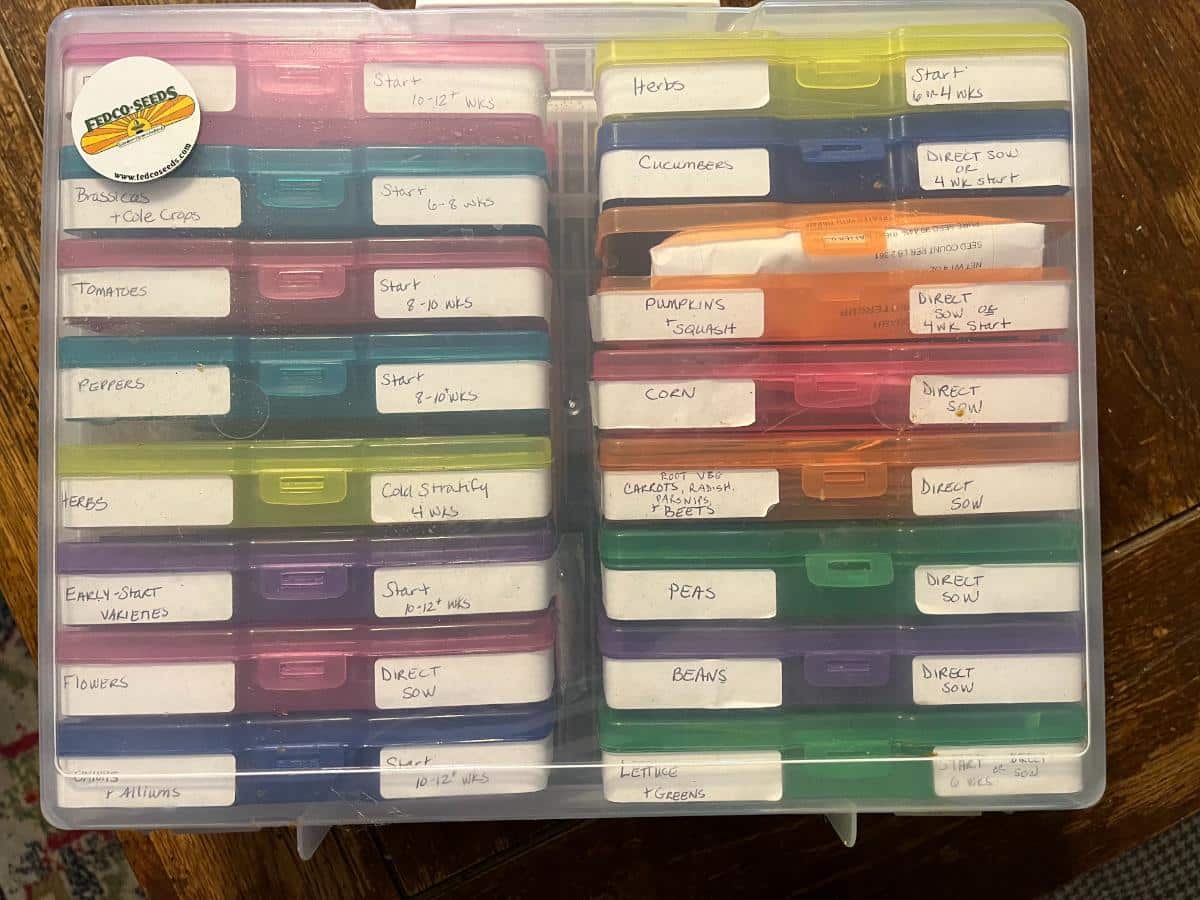

Your last frost date is really the key to deciding when you should start your seeds. Most of the time, when we are starting plants from seed, we are starting annuals. These include frost-sensitive annual flowers and annual vegetable plants like tomatoes, cucumbers, broccoli, cabbage, lettuce, peppers, eggplant, pumpkins, squash…and so many other garden fresh favorites.

The thing is, you don’t want to start most of these annual plants too early. They will outgrow their pots if you do, and then you’ll have to pot them up several times. With good timing, you shouldn’t need to pot up your plants more than once.

You also risk having the plants grow too large as transplants, and that can create problems when planting and problems with transplant shock and plant establishment.

Why do you need to know your hardiness zone before you start seeds for transplanting?

The last frost date is the date that you would expect not to have frost again until the fall (or winter, depending on where you live). We count back from there to decide when to start different types of seeds.

Some seeds need many weeks to start because they are slow-growing. Those plants may need 12 weeks or more. Others grow quickly and are better off not being in pots too long, so they may only need to be started four or six weeks before you expect to transplant them outside.

Better timing of seed starting for annuals also helps you minimize the inputs from you, which means management indoors and requires things like heating and running grow lights. It’s simply more efficient to plan your seed starting times well.

The bottom line: Know your last frost date so you know how far ahead to start your seeds inside so they’re ready on time to move outside.

A note about First frost dates

First frost dates are the date you would expect to have a frost in the fall -- at the end of the growing season. They’re worth knowing so you know how long your growing season is (which is our last key of three).

3. Length of Growing Season

Both frost dates dictate how long your growing season is. First-frost dates don’t play as much into seed starting as last-frost dates do, but they are something to consider.

While the reason to know your last frost date is to know when you can plant most annuals out into the garden, the reason to know your first frost date is to know how long your growing season is.

The time between is the number of days (weeks or months) that you can reliably grow frost-sensitive crops, vegetables, and annual flowers. Those that can tolerate some frost and moderate cold can go in earlier and stay in later. For that, refer to seed descriptions.

Why do you need to know the length of your growing season before you start seeds for transplanting?

You’ll want to know the length of your growing season so that you will know if what you are planting will have enough time before frost hits to mature and produce whatever crop or flowers you are working to grow.

This is also useful information for planning succession crops and fall or winter harvest gardens. It’s not enough just to be able to get a plant in the ground. You need to know there is enough time for it to grow and ripen the fruit or vegetable to eat or the flowers you want to pick!

When you know the length of your season, you can then compare it to the “days to harvest” or “days to maturity” listed for the specific plants that you’re starting from seed. Then, you’ll know if they’re compatible.

The bottom line: Know the length of your growing season so that you can choose seeds and plants that are capable of maturing and producing in the dash between the last and first frost dates!

More Helpful Information for Planning Seed Starting and Starting Seeds:

Leave a Reply