Grafting is another way to propagate, repair, and improve plants. It’s a useful skill to learn, whether you’re grafting a delicate rose onto a hardy rootstock, using a bridge graft to heal an open wound on a tree, or making a 4-in-1 apple tree that bears four different varieties.

Jump to:

What is Grafting?

According to the University of Missouri Extension, “Grafting is the act of joining two plants together. The upper part of the graft (the scion) becomes the top of the plant, and the lower portion (the understock) becomes the root system or part of the trunk.” Although the definition refers to joining only two plants, more than two plants can be grafted

together as long as they are of the same species.

Trees can graft themselves naturally when branches or trees grow into each other through the years.

Starting in about the first millennium BCE, mankind discovered how to graft, bringing about a sea-change in their ability to grow temperate fruits. Eventually, scion grafting was discovered, allowing the domestication of a new range of fruit trees.

Making a successful graft involves lining up the cambium layers of two different species in order to create one new part of a tree or shrub. As the grafted shoot grows, the tissues and cambium combine until the graft is healed and the shoot becomes a part of the plant.

Why Should I Learn How to Graft?

- Propagate plants. Some hybrids and plant selections don’t grow true to seed, so they have to be propagated from cuttings.

- Rejuvenate old trees. Say you want to grow some new apple varieties, but there’s no more room in your landscape. Instead of cutting down mature trees with strong root systems, you can topwork an existing apple tree and graft a new variety onto its trunk. Once the grafts take, you have a brand-new tree growing on long-established roots.

- Increase hardiness, vigor, and disease resistance. A number of rose varieties – most notoriously, hybrid teas – are not tough enough to thrive in the average garden. They were bred for looks, and cold hardiness and disease resistance were often ignored. So, the entire rosebush would be grafted onto the roots of a tough little rose. The hybrid tea then takes on some of the hardiness and vigor of the rootstock and can be grown more widely.

Read more: 12 Low-Maintenance Fruit Trees Anyone Can Grow

- Repair damaged plants. A specimen tree that is damaged can be repaired by growing bridge grafts over the injured area.

- Increase pollination. A number of fruit trees are not self-fertile, which means you have to plant a tree of a different variety nearby. Maybe you don’t have space for two apple trees. Instead, graft scions of different apple varieties onto your tree. Then you get pollinated fruits plus a few new varieties.

- To grow trees quickly. Growing a brand-new tree from a cutting takes a long time. However, grafting a cutting onto a rootstock that’s several years old speeds up the process.

Tools and Supplies Needed for Grafting

Before you start cutting scions (or purchase bundles of them online), you’ll need to invest in a few tools.

Grafting Knife

This is, naturally, the first thing you’ll need for shaving scions and cutting V-shapes into the rootstocks. Choose a good-quality grafting knife that keeps sharp edges even with constant use. A sharp edge will give you a clean cut and less chance of infection.

Whetstones

To keep a sharp edge on your grafting knife, as well as your other gardening tools, use some high-quality whetstones. If your knife is chipped, get a 400-600 grit whetstone. A dull knife creates poor grafting results – and leads to serious accidents. Be a “safety-first” horticulturist.

Read more: 13 Pruning Mistakes That Will Ruin Your Fruit Trees

Grafting Wax

Many nursery operations that bench graft hundreds of trees every winter often have an old crock pot with melted grafting wax, just warm enough to put a finger in without hurting it. Nearby is a small brush to apply the wax to the finished trees, covering all exposed surfaces and filling the clefts. The grafting wax fills and seals any exposed cuts against the elements, diseases, and moisture loss. (Some simply dip the grafted tree upside down in the melted wax so both the scions and the cuts are covered with wax.)

There’s also a grafting wax that can be used in the field, warmed in the fingers, and then applied to the newly grafted scion. Some growers don’t like how the wax sticks to their hands, especially when they’re trying to switch between the wax and the grafting knife and getting wax everywhere. These folks might use tree sealant or even white glue.

Grafting Tape

This is used to wrap finished grafts to protect them from the elements and to apply pressure to the grafts for better healing and sealing. Grafting tape works in much the same way as florists’ tape and needs to be stretched as it’s applied. It can also take as long to master as it does florists’ tape – so get an extra roll, just in case.

Grafting Tools

These confusing-looking contraptions can be bought in different forms, but these can cut amazing puzzle-piece grafts into. Some grafting tools are made for smaller trees, while others are made to handle large branches. If you are new to the art and science of grafting, or if wielding a super-sharp knife makes you nervous, these tools can make you look like you’ve been grafting for years.

Best Practices in Grafting

Here are some rules of thumb for successful grafting.

- Graft only within a species. Apples can’t be grafted onto pears, for instance. Closely related plants have a higher success rate in grafting.

- Make clean, straight cuts. Be sure your knife or shears are sharpened.

- Carefully align the cambium layers so they touch as much as possible.

- Make sure the grafted shoot fits snugly onto the new plant. Any air pockets left in the cuts will allow it to dry out and invite infection, so try to match the cuts as closely as possible.

- Fasten the grafted area securely and solidly so the cambium and tissues join quickly and can transfer nutrients and water between them. Grafting tape made of parafilm stretches to about twice its length and then tightens, allowing for good contact on both ends.

- Protect the grafted areas from water loss, both before and after the grafting operation.

- The best scions are watersprouts from disease-resistant trees. (These are the branches that grow straight up from your fruit trees.)

- Trees never really heal; they seal. Fill in open areas with grafting wax or tree sealant.

Two Guilt-Free Ways to Practice Grafting

If you’d like to practice grafting but the thought of taking a grafting knife to your apple trees makes you feel a little queasy, fear not. Find some less-valuable trees to practice on.

Weed Trees

There are usually some weed trees, such as mulberry or silver maple, growing in and around your yard. You can Frankenstein them with whip and tongue grafts, cleft grafts, and other grafts, then stick bud grafts up and down the sides. Once you have a grasp of the basics (and a sure grasp of your grafting knife), you can start working on your valuable woody plants.

Read more: 12 Tips for Planting Fruit Trees and How to Do It

Hibiscus plants

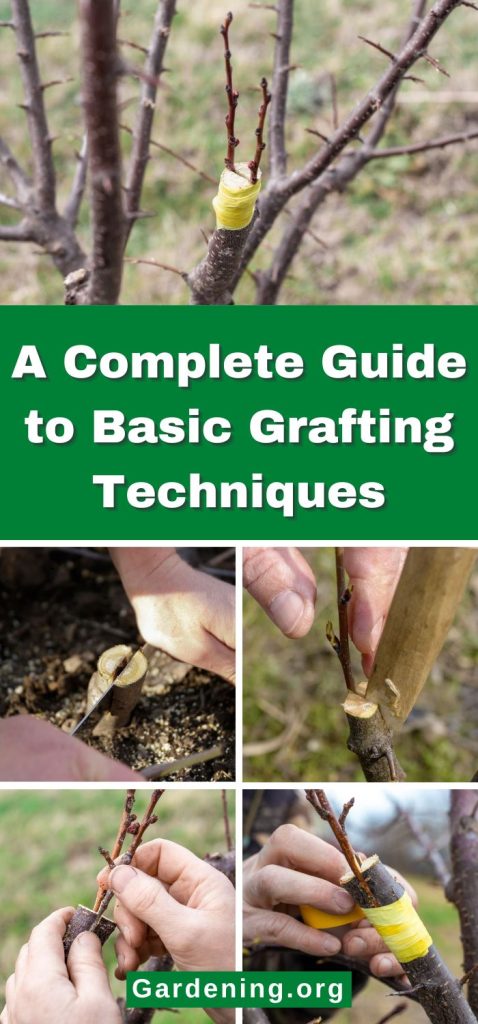

If you don’t have weed trees, or you are trying to learn something like T-budding, which needs to be done in summer when the bark is slipping, then Chinese hibiscus is a good plant to practice upon.

Cornell University recommends using Chinese hibiscus, along with Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis), for grafting practice. They are readily available, are easy to graft, and you can end up with multiple hibiscus with different-colored flowers on each. The university has step-by-step tutorials so you can practice top wedge grafting, T-budding, and chip budding on hibiscus.

A Few Different Types of Grafts

Just as the mariner knows a million ways to knot ropes, a gardener who wants to grow fruit trees will become familiar with a variety of different grafting styles. Knowing which alternate ways of grafting to use will also help the orchardist when they’re faced with a situation in which a normal graft won’t work. It’s an excellent skill to have in the toolbox.

Read on to learn about a few different types of grafts that are commonly used. This article is merely a synopsis because there are a ton of techniques and skills used in grafting and many different ways to go about each particular type.

I have to admit that the more I read about grafting, the more I find to learn! But that can be a good thing.

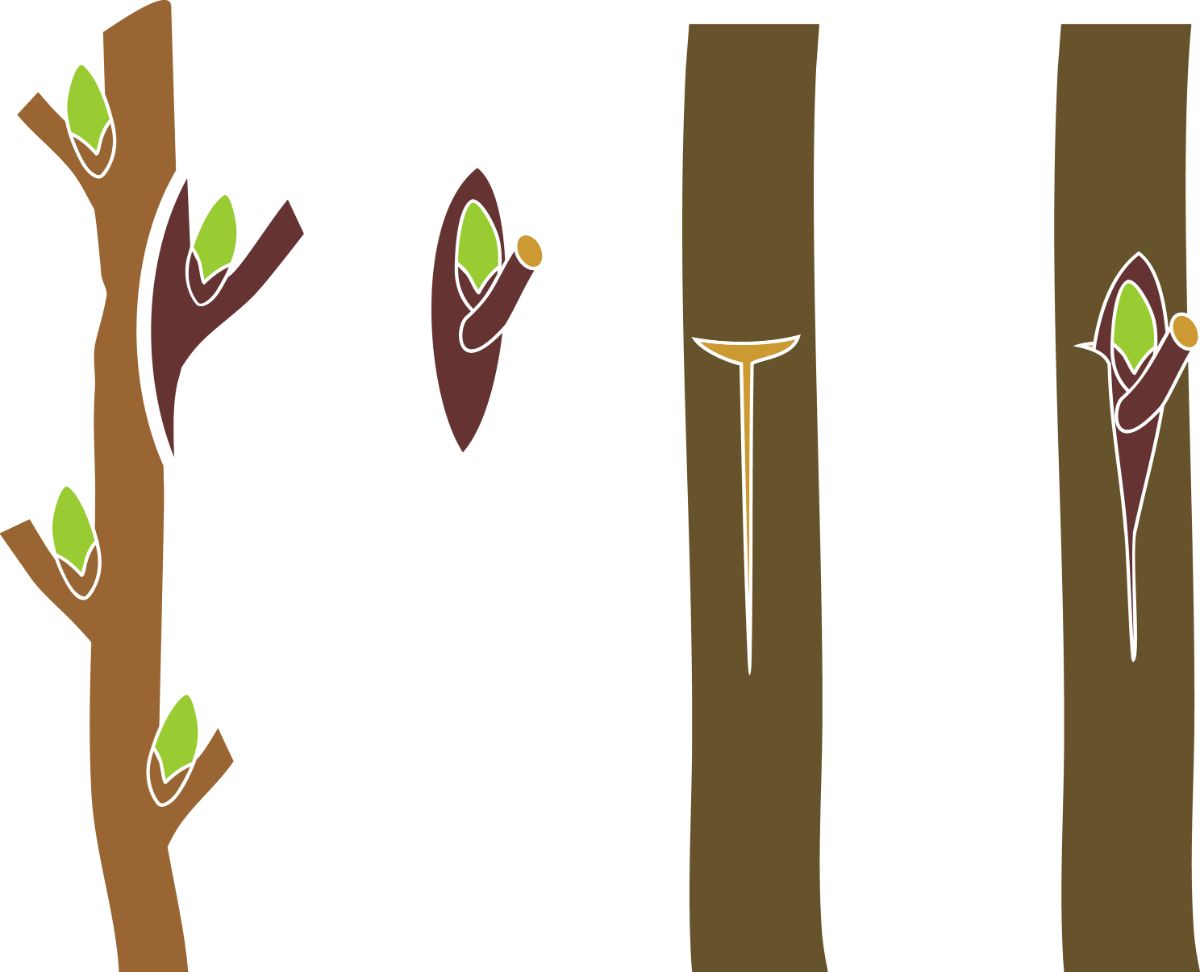

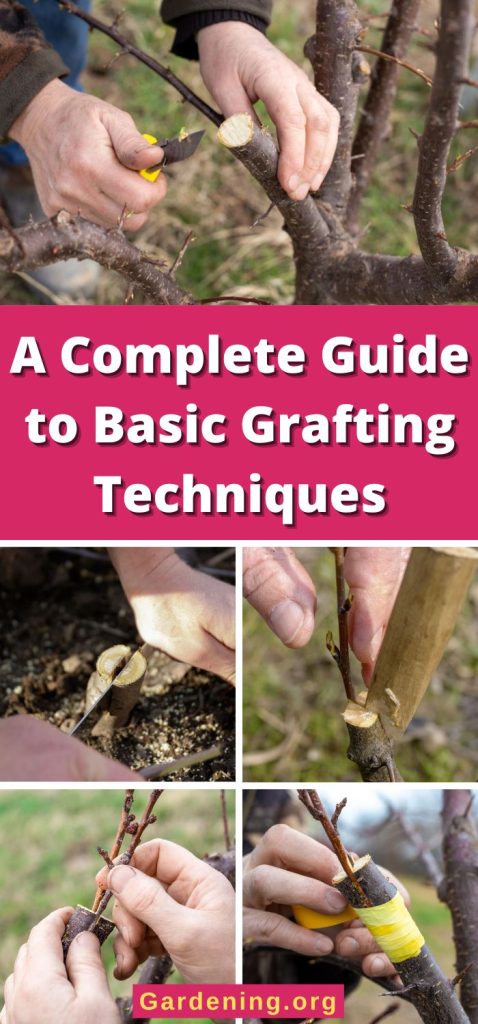

Whip and Tongue Grafting

If the diameter of your scion is close to that of your stock, and they’re less than a half-inch in diameter, use whip grafting. Most fruit growers use this for spring grafting.

(The stock can actually be several things – a one-year-old seedling, a short piece of root, a cutting (rooted or unrooted), or a 1 to 3-year-old tree that you want to top-work to some other variety.)

The whip graft is one of the easier cuts and is commonly used because it’s sturdier when put together, and more surface area of the cambium layers are touching.

Use whip grafting on fruits such as apples, grapes, cherries, and plums. However, whip grafts on quince and peach don’t close very well, so budding is often used instead.

Budding

This grafting technique uses a single bud of the desired variety instead of an entire scion. Budding should be done before the growing season while the bud and stock are dormant.

Budding is much faster and yields more successful grafts than using scions. It uses a small incision instead of a large cut, so it heals more quickly, saves time, and costs less. Budding is popular among fruit tree producers.

Chip budding and T-budding are the most commonly used forms.

Read more: The Ultimate Guide to Planting a Food Forest

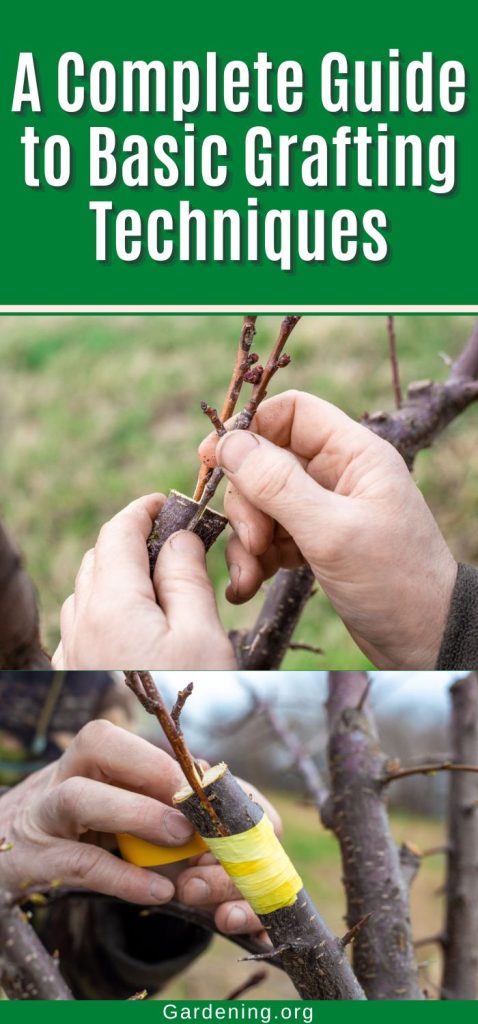

About Top-Working

This grafting method is used on fruit trees to add a new fruit variety to an existing tree or to simply start over with an existing tree with a good root system.

You can topwork a single large branch, or topwork an entire existing tree. But we’ll start small.

Woody plants such as fruit trees, roses, and camellias are grafted via cleft grafting, in which small limbs are split to receive the scions of the new varieties. These limbs are held in place by the cleft, trying to close back up.

Here is a step-by-step guide to top-working a fruit tree.

- Trim back a wide tree branch on a fruit tree where you want the scions of your new variety to go. (To graft a woody plant onto a rootstock, saw off the stock 4 inches above the roots.)

- Now, split the branch. Use the chisel end of a cleft grafting tool or a knife to make the split in the limb. Go down only 2 or 3 inches.

- Insert a small wedge to hold the split open so you can insert the scions. If you have a cleft grafting tool, you’ll have a pick on the opposite end to hold the cleft open.

- Select two scions that have 3 to 4 buds apiece for each graft.

- Cut the scions so they fit snugly into the gaps at the edges. Make the outer edge of the scions slightly larger than the inner edge.

- Now insert the young grafts into the split trunk, with the wide edge facing outward.

- Make sure that all cambium of each scion is touching the cambium of the rootstock.

Then, remove the clefting wedge or pick so the rootstock can close.

- Wrap the branch with grafting tape to hold together the cambium of the scions and the tree. They must stay tightly in contact for the graft to take. The tape also protects the cuts from the weather.

- Then, cover the open wounds with tree sealer compound or grafting wax to protect the area from infection and damage.

- Cut back competing branches so the scions aren’t shaded out – and so they don’t have energy taken from them by taller branches.

A Little Grafting Glossary

If grafting is a new endeavor for you, take a minute to read through this short list and get acquainted with these terms. There might be a test later.

Cambium – In woody plants, the green layer is the source of all growth. If you scratch away the top layer of bark with your fingernail, the green you see just below is the cambium layer.

Scion – A young shoot or twig cut off the parent for grafting or rooting. Scions are cut from desirable cultivars or varieties that the grower wants to propagate.

Rootstock – A plant from which the upper part has been cut, leaving a short stem and mature root system. The scions or buds from another plant are grafted onto this stock.

Budding – Any grafting technique in which a single bud is used instead of multiple buds (such as those on a branch).

Top working – A grafting technique in which new scions are attached to an established tree. This is done to change the tree to a new fruit variety, to attach pollinator branches, etc.

Happy grafting!

Can

Good job. Would be wonderful if you have a few videos on each grating technique. Thank you so much

Rosefiend Cordell

That's a good idea! I'll try to get something out here, video-wise. I'm not the best at videos but fortunately I have kids who can fix stuff for me.