Jump to:

- What is a Pollinator?

- Features and Functions of a Pollinator Garden

- Location Considerations

- Soil

- Sunlight and Shade

- Wind

- Other Nearby Land Uses–Ag Fields, Playgrounds, etc.

- Get Your Neighbors Involved

- Plant Selection

- Native Plant Benefits

- Neonicotinoids–Avoid at All Costs

- Perennials

- Annuals

- Seed vs. Seedling

- Timing–More Than Just Summer Flowers

- Layout and Design

- Right Plant Right Place

- Wet vs. Dry Areas?

- Maintaining and Enhancing Your Pollinator Garden

- Compost

- Watering

- Dealing with Deer

- Replanting

- Removing Old Vegetation

- Mulch

- Other Features

- Feeders

- Shelters and Houses

- What about Container Gardens?

- Get More Involved

What is a Pollinator?

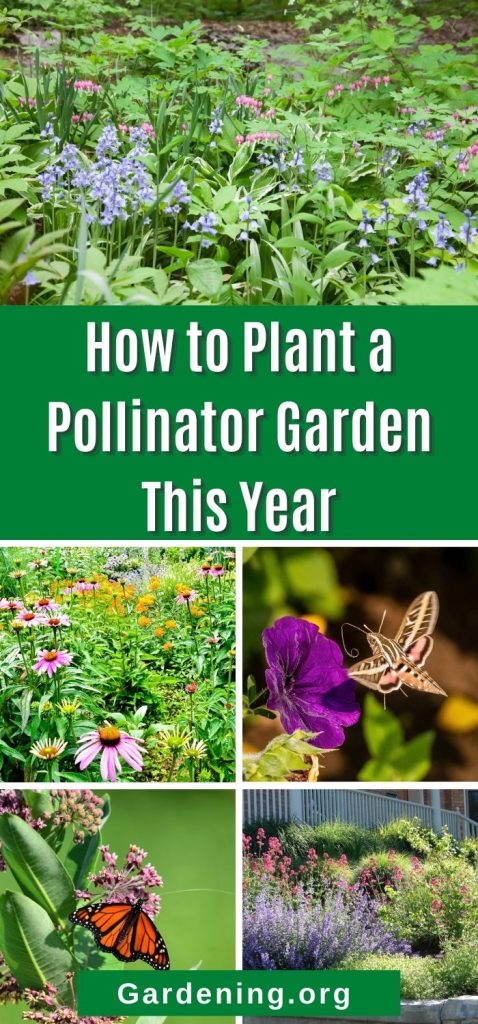

When talking about pollinator gardens and habitats, a pollinator is usually an insect but can be a small bird or other critters. As part of its regular activities, any animal or insect that transfers pollen from one flower to another is a pollinator.

Common examples include butterflies, bees, wasps, moths, hummingbirds, and even some flies.

When we hear the word pollinator, most of us think about bees. There are about 4,000 species of bees native to the United States and as many as 20,000 species worldwide. Unlike the honeybee, which lives in hives, most native bees are solitary and live in homes they make in rotted wood, plant stems, or in the ground.

It is native bees, not our honey-making domestic bees, that do much of the pollination in nature and of our crops. Habitat loss and widespread loss of many of their prime food sources are causing pollinator populations to decline.

Recent research has revealed that moths are important night-time pollinators. Some plants have developed a symbiotic relationship with a specific pollinator. The Yucca needs the yucca moth to reproduce and survive.

Nectar-feeding bats are found in the American Southwest. Beetles have been serving as pollinators for millions of years, and butterflies–while not as effective as bees–are among our most visible and favorite insects in the garden.

Features and Functions of a Pollinator Garden

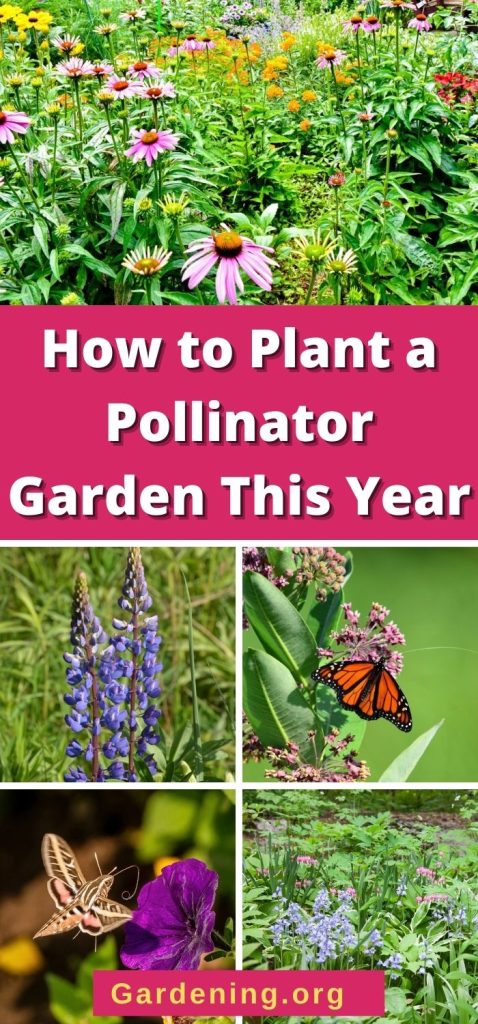

A well-laid-out pollinator garden should provide several habitat requirements for pollinator insects, not only food in late summer when all the flowers are in bloom.

Pollinators need shelter, water, and food, just like other living things. A clean water source can be an excellent attractant during dry periods. Exposed ground and woody debris can provide much-needed shelter, sometimes in scarce supply in more developed areas.

Leave old dead branches and steams to provide resting and security areas. Pollen and nectar-producing flowers and foliage for caterpillars are needed from the first warm weather until the cold, frosty days of mid-autumn set in.

With so much habitat lost during the last two hundred years to urbanization and large-scale agriculture, every tiny bit can help. Imagine if every other yard in the suburbs had a pocket pollinator garden.

Location Considerations

The most important thing is that you plant a pollinator patch or garden, wherever it is. But there are a few items you can pay attention to which will help you succeed at establishing and maintaining your pollinator paradise.

Soil

Just like planning any garden, knowing what type of soil you have to work with guides your plant selection and any soil-building activities you might conduct.

Many pollinator flower species are perennials, so plan to make an initial investment of effort in getting your soil just right at the start. You won’t want to disturb your perennials after their roots have settled in.

For the most part, adding a large helping of compost and some mycorrhiza will be sufficient. Unless you are already working with an excellent fertile loamy soil, add 3-4 inches of compost and work it in with a garden fork or broadfork. If your soil is near neutral pH, no adjustments will be necessary.

Soil found near buildings is sometimes quite different from the area’s norm. Backfilling around foundations or to make the grade slope away from a building is a common practice. Backfilling often uses “fill,” a term for poor-quality leftover soil from a pit or quarry that may be terrible to garden with. Check a spadeful or two to see what you are working with and plan accordingly.

If your soil is excessively sandy or heavy clay, try to select plants that will tolerate those conditions. Working with the soil conditions you have is easier than trying to force a radical change. There are native plants in your area adapted to your local soils, and they will flourish with minimal care.

Sunlight and Shade

Many native flowering plants grow best in full sunlight–greater than 6 hours a day. But the good news is that plenty of pollinator-friendly plants will grow in partial sun or even shade. That shady lawn on the side of the house can be turned into excellent pollinator habitat and reduce your mowing chores.

Take note of how many hours of sunlight your location receives and if it is morning or afternoon light.

Afternoon sunlight is the most powerful. A location that will only receive four hours of good afternoon light may be fine for full-sun-loving plants, but they may struggle in a site with five hours of morning light. Soil that receives afternoon light will also be quicker to dry, at least on the surface.

The amount of sun your pollinator garden receives may not be uniform across the entire plot or bed. If you have some shady and some sunny areas, even better. Diversity of shade and sun, hot and cool, dry and wet, makes excellent pollinator habitat because it supports a wide variety of plants.

Wind

Sheltered locations are better for pollinators than windy, exposed areas. Think of the sweet summertime sounds of bees droning en masse from the flower patch on a warm, sunny day. You don’t see that activity before a storm when the wind is gusting.

If your location could use a little more shelter from the wind, consider a trellis covered in climbing vines, some ornamental trees, a privacy fence, or a hedge to add a little wind protection. Even a couple rows of sweet corn or sunflowers can provide a windbreak during the growing season.

Other Nearby Land Uses–Ag Fields, Playgrounds, etc.

Bees and other pollinators are very susceptible to pesticides. Many agricultural crops are sprayed with pesticides and insecticides to prevent damage to crops. Those chemicals will harm your pollinator garden plants–some of which may be classified by the farmer as weeds–and your pollinator insects. Try to locate your pollinator garden in a site sheltered and protected from activities on neighboring farm fields.

Most bees and other pollinators are passive, not aggressive, and many native bees do not have stingers. But neighborhood children and their parents may not realize this. Consider your garden’s proximity to the neighbor kids’ sandbox or playhouse.

Get Your Neighbors Involved

Misunderstandings can often be cleared up with a bit of communication beforehand. Let your neighbors know what you are doing and why. Have a chat about the expected increased presence of pollinators, and explain they are not a threat.

If your neighbors seem interested in creating their own pollinator patch, even better. Several nearby yards can create an impressive local habitat for pollinators if everyone does a little.

Offer to share a larger order of plants to cut down on shipping or to go in together on renting equipment if needed. Our goal with pollinator habitat is to bring back a bit everywhere.

Plant Selection

I know it well; it can be tempting to grab a cart and stroll the nursery or garden center, snagging every plant with a bee symbol. Instead, try to choose plants suited for your garden bed location. Consider their light needs, preferred soil, deer resistance, and cold hardiness.

But of course, also toss in that one that grabbed your attention from across the greenhouse. All gardens are pollinator habitats in one form or another, and any garden space is better than mowed green grass. Pick plants that make you happy as well.

Native Plant Benefits

When possible, pick native plants for your area. Native plants and the pollinators present in your area have developed together over thousands of years. That doesn’t mean you can’t add some non-natives, as long as they are not invasive. Just make sure the majority of your selections are native.

Finding which plants are native to your area can be a challenge, but many resources are available. This native plant finder from the Audubon Society is a good starting point. You can search by your zip code if you live in the US.

You can also Google search native+plants+your location to find other resources, including local nurseries and hyper-local information. Ask around at a local garden club or use this link to find your local County Extension office if you are unsure how to get ahold of them.

Adapted for Survival

Native plants are adapted to your climate: the seasons, high and low temperatures, day length at first and last frost, precipitation, etc. They are much more likely to be low-maintenance and much more likely to survive and thrive.

Preferred, Familiar, and Expected Food Source

Native flowering plants provide a familiar food source for pollinators. Sometimes they will not accept a substitute. The Karner blue butterfly is an endangered species. While the adults will feed on many nectar-producing flowers, the caterpillars can only feed on the leaves of the wild blue lupine.

Neonicotinoids–Avoid at All Costs

Neonicotinoids are relatively new pesticides. They are widely applied as sprays, injections, and even seed coatings. They are persistent in the plant, showing up in the pollen and nectar. Recent data released by the EPA indicates these chemicals may be causing extreme harm to our pollinator populations.

Definitely, they need to be kept out of a pollinator garden. Look for vendors that don’t use neonicotinoids. Often, this information will be on their website or on a sign near their native plant section. If a seller doesn’t know or can’t provide the information, it might be best to move along.

Perennials

Many native flowering plants are perennials and make a great addition to your pollinator garden. They will be low-maintenance plants that come back year after year. Perennials can save on expense and labor and provide a continued and properly timed food source for pollinators.

Many perennial flowers and plants don’t seem to be doing much in their first year. The old saying is that perennials Sleep-Creep-Leap, meaning that the first year they don’t appear to grow much, the second year they put on some size, but the third year is when they will take off and fill the space.

In the first year, your new perennial plant is recovering from transplant shock and is putting its energy primarily into making a large, extensive root system. Be patient. By the third season, they will have expanded and become that lush, bloom-filled space that inspired you when browsing pictures on Pinterest.

Annuals

Don’t be afraid to add a few annual flowers or veggies to the mix. Some perennial plants like lavender are commonly grown as annuals if you garden in a colder climate. If left to flower and not eaten for dinner, vegetables like broccoli are a bee magnet.

Annuals can also fill in bare spots while waiting for those perennials to grow and fill out and provide some food for your pollinators. Recent research into the potential value of annuals grown as cut flowers indicates that even the limited time these flowering plants are available provides some benefit.

Seed vs. Seedling

Seedlings purchased from the garden center offer some instant gratification, and who doesn’t like a little of that? But don’t overlook buying seeds from a native plant vendor.

Many native types of grass and forbs can be broadcast seeded successfully, offering a low-cost and effective way of creating and filling a larger space.

Often a greater variety of plants is available as seed than as started pots. If you can’t find what you are looking for at the garden center, consider ordering from a native plant vendor’s website and starting the seeds on your own. Most sites and catalogs selling native plant seeds provide good instructions on each variety’s needs.

Timing–More Than Just Summer Flowers

Pollinators need food and habitat in the summer and throughout their life cycle. This includes not only the adult stage but the larval stage as well. A well-planned pollinator garden will provide food and habitat from early spring through frost in the fall.

Plant early, mid-summer, and late-season blooming plants to provide nectar all through the warmer months. Some plants are needed by the larval stage as well. Remember milkweed plants and the caterpillars of the Monarch butterfly?

Take a moment to research and plan your plant selections to ensure continued availability. If you are trying to help a specific pollinator species, make sure your garden reflects that pollinator’s needs.

Layout and Design

Right Plant Right Place

You may find it helpful to draw a sketch of the shape of your pollinator garden to assist with the layout. If you have shady areas or different soil types, mark those in as well.

Place them in circles on your map once you have selected plants for your bed. Group plants with like needs together. To simplify watering or irrigation, keep plants with higher water needs together, likewise with more drought-tolerant plants.

Resist the urge to scatter all your plants evenly throughout the space. Many pollinators prefer to feed only on one species at a time when foraging. Clump or group plants together instead of planting them here and there to aid the pollinators in finding them. Create clusters instead of a mosaic.

Wet vs. Dry Areas?

Many pollinators, especially native bees and butterflies, need a source of water. A shallow birdbath in the patch can provide more than clean birds. A damp shady patch of soil is a water and mineral lick.

If you have an irrigation line in your garden, consider making a wet patch out of direct sunlight where water can make several small pools or puddles. A dead-end hose run (cap off a short section of hose) with a couple of small holes can make an excellent water lick for insects. Add a few small rocks for landing areas.

Try for moist and damp, not muddy and messy.

Maintaining and Enhancing Your Pollinator Garden

Compost

If you have selected some plants that only thrive in sandy, droughty soil, add some compost. Gently work it into the top inch and let nature do the rest.

Compost provides a much more stable source of plant nutrients than some blue powder out of a hose and is more available to the plants.

Resist the temptation to mix it in deeply, as tillage will destroy many fungal mycorrhizae, bacteria, and other soil life that is just getting its groove on in your permanent pollinator bed.

Watering

If you use native plants, once they are established, they should need minimal water. Drip irrigation can provide simple and affordable irrigation to areas that need more frequent watering.

Set the irrigation on a timer to water in the morning before the day’s heat builds. Don’t overwater and create a muddy mess.

Dealing with Deer

Many plants are lightly browsed by deer in the wild, but they may all get heavily browsed when planted together with tasty treats. Deer supposedly do not like daffodils, but mine get a haircut every year as they are near some hydrangeas that the deer love.

Deer fencing is effective but may not be the aesthetic you want in your yard. An eight-foot-tall fence can be unsightly and may not even be allowed by your municipality.

Deer repellents work with varying degrees of effectiveness. They are often messy and stinky and need to be reapplied regularly. I have found that when the deer are truly hungry, repellents do not stop them, but if there is plenty of other stuff to eat, the repellents may be enough to get the deer to move on.

If you look on social media, you can find videos of deer being scared off by motion-activated sprinklers. I have not tried one of these, but they look hilarious. If you have had success keeping deer away with these, drop us a line and let us know in the comments section below.

Replanting

Some plants will fail to thrive despite the best efforts, get overbrowsed by deer, become rabbit food, get smashed and mowed by a lawnmower run amok, or otherwise die.

You may find that a particular plant species is not suitable for your location, even though it should have been.

Use care when replanting and try not to disturb the roots of neighboring plants too much. Remember that a new plant may need more frequent watering than the rest of the bed, which has been established for a couple of years.

Removing Old Vegetation

Wait to remove old dead vegetation until early spring. Leaving it in place over winter provides essential habitat for insects hiding dormant through the colder months.

Consider leaving some larger, woody debris as well. It may not look as tidy, but the pollinators need it.

Mulch

In my opinion, a nice layer of mulch in your garden is sort of a miracle problem solver. It evens out moisture, keeps soil from developing a hard crust on the surface, and suppresses weeds. Mulch even adds to the soil structure, health, and fertility as it degrades.

But for a pollinator garden, consider leaving some spots bare. Many ground-nesting bees need some bare soil to make their home.

Other Features

Feeders

A hummingbird feeder, or several, can be an excellent addition to any backyard or front yard pollinator patch.

Visit the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center website to learn more about hummingbird feeders and how to make your own safe hummingbird nectar for your feeder.

Shelters and Houses

Bee and insect “houses” can be made out of logs with holes drilled into them, cardboard boxes, or more imaginative purpose-built structures.

The removal of woody debris and wooded areas in our suburbs has created a native bee housing shortage.

Check out these instructions on how to build a mason bee pollinator house.

What about Container Gardens?

Maybe you don’t have a yard or only a tiny space. Can you help the pollinators with only a few planters on a deck or patio? The answer is yes.

Every year I plant Salvia spp. in a large planter on my deck. I like the tall, spiky blue flowers that keep going all summer long until the frost. I found that the bees, butterflies, moths, and especially the hummingbirds love it.

Of all the flowering plants in my gardens and on my deck, the Salvia is probably the ‘busiest.’ All I have to do is water it every morning. The hundreds of blue flowers do the rest. It is not native to my area–too cold here–so I grow it as an annual in a container. Is that habitat? The constant buzz tells me it is.

Get More Involved

June is National Pollinator Month.

Celebrate by visiting the National Wildlife Foundation page, sign up for a newsletter, certify your garden, and put out a sign to inspire your neighbors, or even apply for a grant to start a pollinator garden in your community.

Just search pollinator+garden+grant for ideas.

Leave a Reply