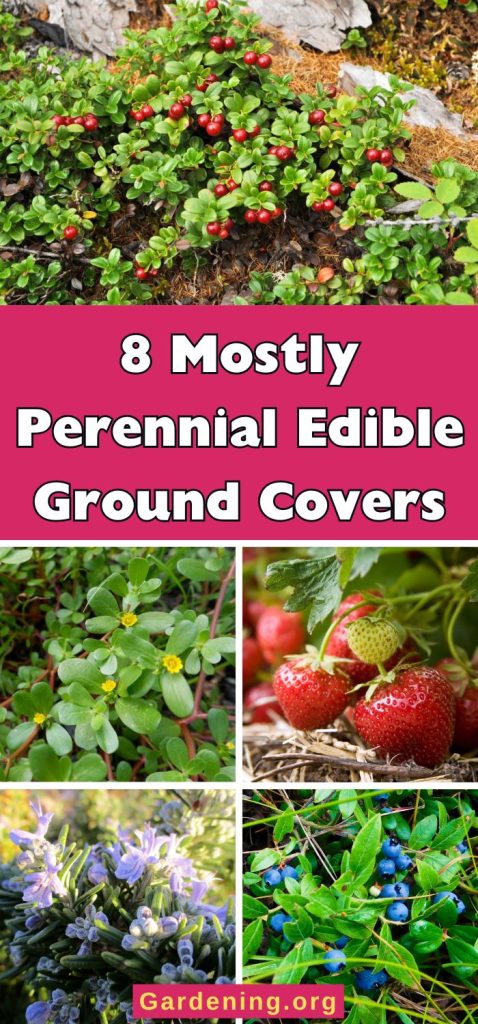

Ground cover plants serve many purposes in the yard and garden (like weed control, erosion control, and moisture retention). And here’s one more – food!

Indeed, we often ask groundcover plants to fill in a lot of soil and space. So why not put them to an even better and higher use? Like growing food or herbs for your kitchen!

It’s no harder to grow ground-covering edible plants than it is to grow ornamental groundcovers. You’re putting the work in anyway, so why not reap a rewarding harvest from them, too?

Jump to:

- Eight Double-Duty Edible Ground Covers for Food, Weed Control, and More

- 1. Strawberries

- 2. Low-Bush or Ground Blueberries

- 3. Cranberries

- 4. Sweet Potatoes

- 5. Creeping Thyme

- 6. Creeping Rosemary

- 7. Wintergreen (aka Tea Berries, Teaberry, Checkerberry, or Boxberry)

- 8. Purslane

- Other Ground-Covering Edible Plants to Consider

- Tips for Growing Edible Groundcovers

Eight Double-Duty Edible Ground Covers for Food, Weed Control, and More

We’ve collected eight of our favorite edible ground cover plants, chosen for their ground covering capabilities, but their popularity as food and culinary, plants too.

Many of these plants grow as perennials, even in lower zones. Some are annuals, which may also depend on where you live and garden.

For the best erosion control and lowest maintenance, look for plants that are perennials in your zone (or zone equivalent).

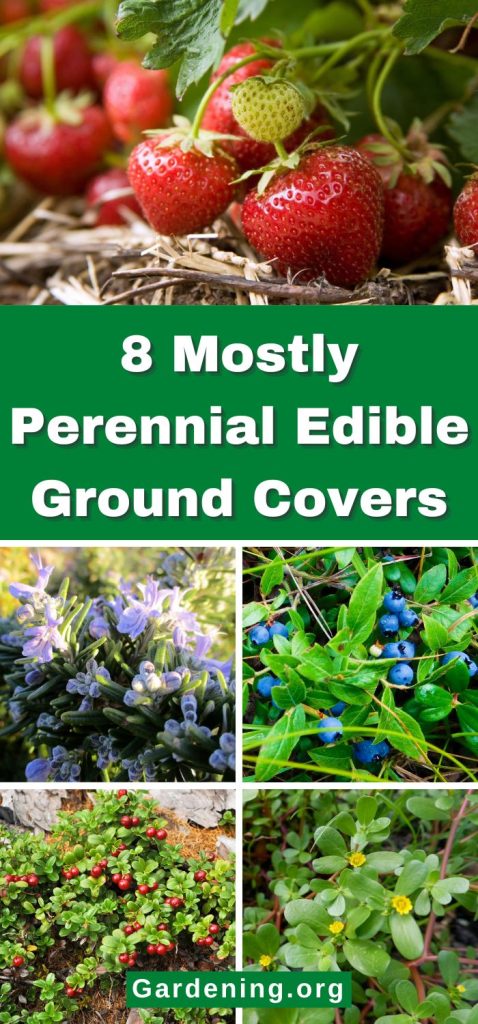

1. Strawberries

Strawberries will remain green all season long, and in the fall, you’ll see leaves taking on some reddish tinge. The blossoms, which are white on most plants (though there are some varieties that blossom pink), look quite nice when in bloom.

Alpine varieties work well because they don’t tend to send out too many runners, and so they don't get out of hand. They feature small edible berries, but the berries don’t steal the show. They’ll also continue to produce throughout the growing season, as alpine strawberries are day-neutral. The berries are larger than most wild strawberries, about twice the size, and have a deep, sweet flavor (considered better in flavor than large, cultivated berries, but with lower yield due to size).

If you like the looks of and benefits of large berries (larger yields, primarily), there are many varieties that will suit. For a truly self-spreading strawberry that will create a mat over the ground, opt for a June-bearing variety because they will send out the most runners, which means they’ll cover the most ground and do it quickly (within the first year).

Space plants about 12 inches apart for a matting ground cover.

Everbearing and day-neutral varieties are nice, too, and the benefit to growing them is that you get large flushes of strawberries in the early summer and again in the fall, with a light, continuous harvest throughout the months in between. They don’t tend to send many runners out, though (if at all), which means they won’t spread as a ground cover quite as nicely.

However, you can plant everbearing strawberry plants more closely together to block the weeds by denying the weeds light and resources. As a groundcover, plant everbearing strawberries about 8 to 10 inches apart, depending on the variety (use the plant size as your guide). Each plant will spread to a diameter of about 8 to 12 inches.

Most strawberries are hardy in zones 4 through 8, but there are varieties that are hardy as low as zones 2 and 3 and up to zone 10. For the higher and lower zones, you’ll need to pay more attention to choosing a variety that is perennial in those zones. They like light, loamy soils on the slightly acidic side (pH 5.3 to 6.5).

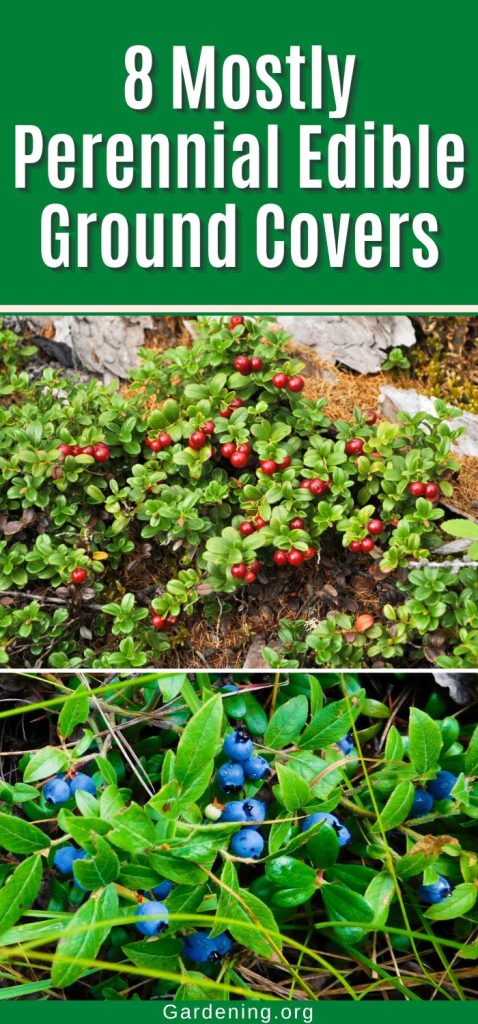

2. Low-Bush or Ground Blueberries

Many, if not most, of the wild-grown blueberries that you buy in grocery stores are low-bush blueberries. They grow in ground covering mats across huge blueberry fields. They're easy to harvest with hand rakes (or you can pick by hand). In fact, it is recommended that you pick by hand for the first year or two of harvest so that you don’t accidentally dislodge young plants.

Low-bush blueberries like acidic soil, down to a pH of 4.0 to 4.8. This makes them good companions for other acid-loving bushes and landscape plants like rhododendrons and azaleas.

The acidity of the soil that blueberries grow in helps to control weeds even more because most weeds do not thrive in a pH that low. If your soil is not acidic enough for blueberries, you can amend it with elemental sulfur or aluminum sulfate.

Lowbush blueberries grow to about six inches tall, and they spread from 12 to 14 inches per plant. They spread from rhizomes and, by reseeding, for the fastest cover as a ground cover, plant blueberry plugs or nursery plants 12 inches apart. To cover a larger space, you can space the plants even more widely apart, but it will take longer for the ground to fill in – up to three to five years.

The University of New Hampshire recommends removing weeds before planting and mulching the plants with wood chips and/or pine needles to reduce weed competition while the plants spread and become established. Once established, the blueberries form a mat and do a nice job of keeping weeds in check.

Lowbush blueberries grow in zones 2 through 8 (though in zone 2 or 8 you will need to check the variety for hardiness). They do not have high soil requirements, but they do well in gravelly soils with a layer of organic matter over them (called “duff”). This is similar to the duff that occurs naturally on forest floors. Needles, leaves, chopped leaf/leaf litter, and compost are effective ways to recreate duff in the home garden.

One of the best things about using lowbush blueberries (or “ground blueberries” as many people commonly call them) is that the plants are attractive in all seasons. In the spring they have nice green leaves and then small flower blossoms that turn into berries. In the fall the leaves turn a pretty red, and when the leaves fall, they have red-colored stems that brighten the landscape in winter.

For the best harvest, plant lowbush blueberries in full sun. The plants will live in part shade and filtered shade but won’t produce berries well when shaded.

3. Cranberries

Cranberries are popularly known as plants that are grown in wet bogs, but cranberries do not need bogs to grow. They are highly adaptable plants that can be grown in anything from rocky, dry soils to bogs.

Bog growing is in part popular because of the ease of harvesting, but in fact, dry-harvested cranberries keep better and can last longer, and there is a distinct market for them. They are easier to handle, too.

Cranberries are much like lowbush blueberries in that they are short, hardy plants with attractive leaf, blossom, and stem colors throughout the changes of the seasons. They are naturally ground covering.

Cranberries also prefer low pH soils, so it is possible to mix and match them with blueberries (they have a later harvest period). You might consider a carpet of lowbush blueberries that bleeds into an adjoining carpet of low bush cranberries so you have more than one edible harvest from your ground covers.

Cranberries, once established, can be raked like lowbush blueberries for easier harvesting, too. Dry-harvested cranberries are firm and tolerate raking and mechanical harvesting.

Cranberries are hardy in zones 2 through 7 and equivalent locations. They are naturally disease and pest-resistant.

4. Sweet Potatoes

The drawback to using sweet potatoes as a groundcover is that if you plan to eat them, you’ll have to dig them. You’ll want to keep this in mind when you’re planting your vines. But the vines extend far beyond where the tubers are in the ground (the edible portion of the sweet potatoes – the actual potatoes).

You can plant the sweet potatoes away from other plants that you don’t want to disturb later when you dig them. The potatoes will grow underground below the plant’s crown – around where you planted the slip.

Typical spacing for sweet potatoes is about three feet apart, but for ground covering, you’ll want to plant them closer. You can plant as close as 12 to 24 inches apart (but the closer they’re planted, the trickier it can be to dig them).

There are sweet potato vines that are considered ornamental, which can be grown as groundcovers and don’t need to be dug, but they do not produce tubers that are usually eaten (because of their size).

Sweet potatoes are usually grown as annuals (mostly because we want to dig and eat those sweet, nutritious treats!). They can be grown as perennials but are only hardy in the warmest of climates, in zones 9 through 11.

5. Creeping Thyme

Creeping thyme, though not usually the first choice for growing as a culinary herb, can be eaten and makes a nice flavoring in any dish where you would use a higher, bushing variety of thyme. It is quite low maintenance, easy to grow and care for, and offers a variety of benefits.

Creeping thyme is a bit more difficult to harvest because it grows in a low mat that follows the ground, which is part of why bushier plants are preferred as a harvesting herb, but otherwise there is no reason you can’t eat creeping thyme. It is an excellent candidate as a double-duty edible groundcover.

One of the biggest advantages of growing creeping thyme as a groundcover is that it can handle foot traffic and be walked on. When it is walked on, it emits a lovely thyme fragrance.

That said, you probably want to take your harvests from thyme that is not frequently walked on.

Fragrant thyme plants also repel insects and biting insects like no see-ums, biting black flies, and mosquitoes. This means this plant can do more than double duty when thoughtfully placed!

For a groundcover, plant creeping thyme plants 8 to 12 inches apart. They will grow together and form a weed-blocking mat. Creeping thyme is typically hardy in zones 4 through 9 and locations with equivalent conditions.

You can also use herb or culinary thyme varieties as a groundcover or border if you plant many bushes close together (about 8 to 12 inches apart), but you may need to do more mulching and some intermittent weed pulling.

6. Creeping Rosemary

Creeping rosemary is another excellent edible herb plant that can be used as a groundcover. It is similar to the bushing, upright varieties that are often grown in herb gardens.

Creeping rosemary is a fast spreader, and a single plant can spread as far as three to five feet, depending on the variety. The height of creeping rosemary (also called trailing rosemary) varies by variety and ranges from eight to 24 inches high.

Height can be kept in check by frequent trimming, which may happen by default when you cut the plant to use in cooking or drying and preserving.

One drawback of creeping rosemary is that the plant is a warm-climate plant and is only hardy as an overwintering perennial in zones 7 through 10. Look for a cultivar that is hardy for your area (not all varieties are hardy in zone 7). About the lowest sustained winter temperature that creeping rosemary can tolerate is –15 degrees Fahrenheit (-26 C).

Northern growers are not likely to be able to grow this as a perennial, but annual growing is an option.

If you can’t grow creeping rosemary as a perennial, you can take several cuttings of the plant in the fall to root and propagate over winter and then replant the propagated plants in the spring.

Creeping rosemary can also be grown in containers, and it makes a lovely spiller. While this won’t help you as a groundcover, it can help to keep your plants going for annual planting (because you can bring the container inside for winter and plant it in the ground in spring). It should be noted that even the perennial variety has a lifespan of only about 10 years, so keep this in mind and propagate cuttings near the time when the groundcover might need replacing.

The plant will grow small purple flowers if allowed to go to flower, and these are appreciated by pollinators and bees.

Creeping rosemary is a Mediterranean herb that thrives in sandy and well-draining soils. Be careful not to overwater, which causes root rot and fungal issues. It is a good candidate for poor soil areas, rock garden fillers, and to grow trailing over the top of a retaining wall.

7. Wintergreen (aka Tea Berries, Teaberry, Checkerberry, or Boxberry)

Wintergreen is a small, leafy plant that is native to woodland areas in many locations. It has a subtle, minty, wintergreen flavor (much like the gum of the same name).

Winterberries are evergreen plants that hold their leaves through the winter, so they’ll give you some color even in the dead times of year. They are very hardy and are perennial in zones 3 through 8.

Winterberries grow small white flowers in the spring, which turn into small red berries in the summer. The berries will remain on the plants in the winter if they are not harvested or eaten by birds and wildlife.

Winterberry truly is an all-season edible groundcover that can also be a helpful natural food source for overwintering birds and other wildlife.

Both the leaves and berries of the winterberry are edible. They are often used in teas, chewed whole and raw, or added to things like fruit salads for a bit of minty flavor.

8. Purslane

Purslane grows naturally in many gardens, and is often considered a weed, but is truly a useful, nutritious edible plant. If you’ve ever dealt with it in garden spaces where it wasn’t wanted, you can attest to its ability to spread and act as a groundcover.

The plants grow about three inches tall and will spread from 12 to 18 inches.

Purslane is considered an “accumulator” because it has deep roots that pull up nutrients from deep in the soil that many vegetable plants cannot reach. As such, it is rich in iron (the second highest level of any edible plant!) and it contains a lot of calcium, magnesium, and potassium, along with Vitamins A, C, and E, and other important fatty acids and nutrients.

Because of its bio-accumulating properties, purslane is a good cover crop and “green manure” that returns minerals and nutrients to the upper levels of soil if/when it is tilled in.

Purslane can be eaten and prepared in a variety of ways. It can be eaten raw, sauteed, or used as a thickener for soups and stews, among many other culinary uses. Late in the season, the stems are thick and large and can even be made into pickles.

In the late season, the stems turn a reddish color, giving them multi-season appeal.

Purslane is an annual plant in most locations and will not survive frost, but you can keep container plants of purslane or propagate it for spring planting. It also readily resows from seed (self-seeds -- which is how it comes to live in most vegetable gardens where we think it’s a weed).

There is a winter variety that can survive temperatures down to 5 to –15 F (-15 to –26 C). This may survive as a perennial, depending on location.

Other Ground-Covering Edible Plants to Consider

The eight plants we’ve highlighted here are eight of our favorites, chosen for their ground covering capabilities and for their popularity as culinary foods. They’ve also been chosen because they stay fairly low to the ground, in the manner that we usually expect groundcovers to grow.

There are many other edible plants and herbs that can be used as groundcovers, too. Many of these are taller than what is typically used for groundcovers, but depending on the space and companions, these can work very well as dual-purpose edible groundcovers, too.

Here are some others to consider:

- Partridgeberry (an evergreen shade/woodland plant similar to Wintergreen, but it is a different plant)

- Mint (and other plants in the mint family)

- Vining nasturtiums

- Oregano

- Sorrel

- Violets

- Chamomile

- New Zealand spinach

- Strawberry spinach

- Lingonberries (similar growing conditions and plant as cranberries, native to Scandinavia and prized for jams, syrups, and preserves, now grown all over the world)

- Creeping Oregon grape

- Parsley (a good choice for a groundcover herb; plant in abundance, so there’s enough for you and for the swallowtail butterflies whose caterpillars love it so well!)

Tips for Growing Edible Groundcovers

- Plant closer than normal to fill empty ground and help block weeds and retain moisture

- Some plants may need more attention and care when planted intensively, so watch for signs of fungal disease and treat at first signs

- Vining and spreading plants will cover more ground

- Match your groundcover to the soil and growing conditions

- Plant edible groundcovers with companions with like growing requirements – for example, full sun, rich soil plants together, sandy or light soil plants together, shade and part-sun plants together, acid-loving plants with acid-loving plants

- For the lowest care and maintenance, choose edible groundcovers that are perennials in your area

- Edible plants, even perennials, can have heavy feed needs, so amend the soil as needed annually

- If a plant is not perennial and/or will not self-seed next year, take cuttings in the fall to propagate, and you will never have to buy replacement plants

- Perennial groundcovers are the most efficient and easiest to maintain, but if you want a plant for its flavor and culinary uses, consider planting it in a smaller area and use perennials for larger spaces to reduce planting and maintenance

- Look for varieties that are hardier and/or that match the area in which you live to find the most perennial edible groundcover options

Leave a Reply