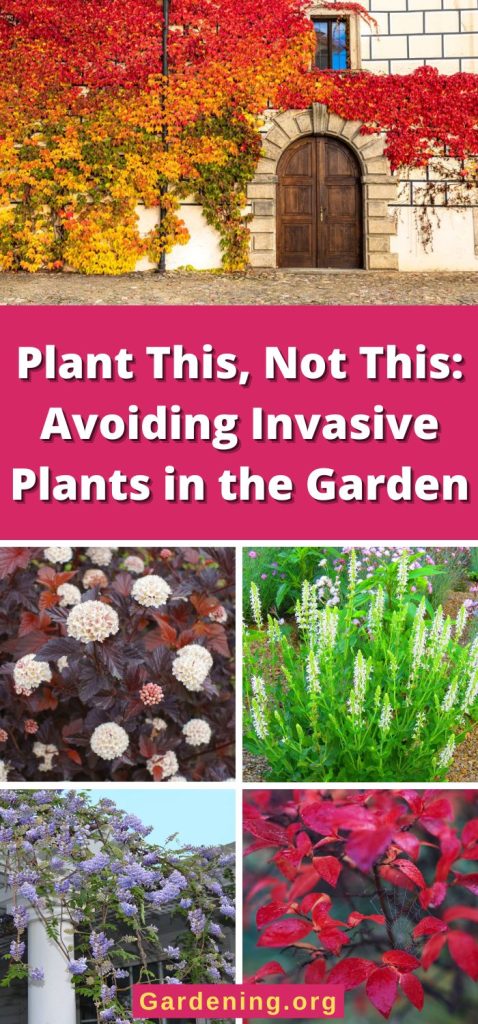

Invasive plants can pose big problems in gardens. They rapidly spread, drown out lower-growing plants, and can prove difficult to manage. But even worse, when invasive plants escape into the surrounding ecosystem, they can outcompete native plants, destroy wildlife habitats, and wreak havoc in other ways too.

Controlling invasive plants with natural methods can do a lot to keep these noxious plants from spreading. But if you want to tackle invasive plants once and for all, it’s also essential to do what you can to keep invasives from entering your garden in the first place. And one way to do that is to swap out invasive plants for native plants and slower growers that have all of the aesthetic charms of ornamental invasives but without any of their inherent risks!

Jump to:

- 12 Invasive Plant Swaps for Your Garden

- 1. Swap ninebark for barberry.

- 2. Swap coral honeysuckle for Japanese honeysuckle.

- 3. Swap summersweet for butterfly bush.

- 4. Swap blueberries for burning bush.

- 5. Swap chokecherry for Chinese privet.

- 6. Swap American wisteria for Chinese or Japanese wisteria.

- 7. Swap Virgina rose for beach rose.

- 8. Swap crossvine for wintercreeper.

- 9. Swap Virgina creeper for English ivy.

- 10. Swap buttonbush for autumn olive.

- 11. Swap Pennsylvania sedge for lilyturf.

- 12. Swap clumping bamboo for running bamboo.

- Frequently asked questions

- What does it mean if a plant is invasive?

- Has an invasive species ever been good?

- What is the best way to remove invasive plants from the environment?

- How are invasive species transferred?

- Can invasive plants harm humans?

- Why are native plant species important to an ecosystem?

- Summary

12 Invasive Plant Swaps for Your Garden

Whether you’re installing a new garden and you’re looking for new plants, or you’re rehabbing an existing garden where invasive ornamentals are already growing, you will find plenty of planting suggestions in the list below. The plant swaps we’ve selected have all of the beauty of invasive plants, and they can be used in much of the same way in garden landscapes as their aggressively growing counterparts. But these plant swaps actually support native wildlife, and they don’t require as much maintenance to keep them in line!

1. Swap ninebark for barberry.

Common and Japanese barberry plants may look pretty with their bright red berries and leaves that burn crimson in spring and autumn. But barberry plants spread rapidly via their berries, and they can form dense thickets that smother out native plants and reshape ecosystems over time. Even worse, barberry stems are covered in spines that can make them a nuisance to get rid of, and barberry shrubs are known to provide the perfect habitat for ticks that spread Lyme disease!

Due to all of the drawbacks of barberry plants, it’s best to avoid growing these invasive shrubs if you can help it and to remove any existing shrubs that are growing in your garden. However, if you love the look and feel of barberry plants, there are several easygoing shrubs that function as perfect barberry swaps, and they don’t have any of barberry’s less pleasant characteristics!

Ninebark (Physocarpus spp.) is an ideal replacement for barberry as this plant is native to North America, and it provides habitat and food for native wildlife. But beyond their utility in the garden, ninebark shrubs offer season-long interest as they bloom in spring, produce bright red berries in summer and fall, and they feature interesting, exfoliating bark in winter as well! If you don’t love ninebark, you may want to try out winterberry holly (Ilex verticillata), another North American native that produces bright red berries towards the end of the season.

2. Swap coral honeysuckle for Japanese honeysuckle.

Japanese honeysuckle is still commonly sold in plant nurseries, but this vining plant can cause a lot of problems. As they spread, Japanese honeysuckle vines can clamber over 120’ of space, and they can climb up trees and strangle out other plants that get in their way. Many gardeners grow Japanese honeysuckle for its dainty flowers and rich fragrance, but with all of the damage these plants can do, planting Japanese honeysuckle vines in garden beds hardly seems worth the trouble!

But while Japanese honeysuckle isn’t a great choice for gardens, there are plenty of other ornamental plants that can be swapped in instead. Some of the most obvious options are native honeysuckle plants, like coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), which have the same general look as their invasive cousins, but they don’t grow as aggressively. In fact, coral honeysuckle is arguably an even showier plant since its spring-blooming flowers are a bright pinkish-red color!

As lovely as coral honeysuckle is to the eyes, this plant doesn’t have the same exotic fragrance as Japanese honeysuckle. For this reason, if you are drawn to Japanese honeysuckle for its rich aroma, you may want to try out mock orange (Philadelphus coronarius) instead. While mock orange isn’t a climber, it does have a heady, citrus-like scent that will make your garden feel like the tropics!

3. Swap summersweet for butterfly bush.

Butterfly bush undoubtedly has been a popular choice for pollinator gardens for a while, and many gardeners still choose to grow it. After all, the butterfly bush has a lot to recommend it. Butterflies and pollinators flock to it, and its oversized pink, purple, and blue flowers add a bold pop of color to gardens, and they emit an intoxicating perfume, too.

But as beautiful as butterfly bushes are, these plants can outcompete natives in areas where they grow perennially. On top of that, pollinators often prefer butterfly bushes to native plants, which might at first appear to be a good thing. However, if pollinators are too busy pollinating butterfly bushes, they may never get around to pollinating native plants, and native plant populations can suffer as a result.

To avoid these issues, consider swapping out your butterfly bush shrubs with summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), a native North American plant. Like butterfly bushes, summersweet’s fragrant and showy flowers provide lots of nectar and pollen for pollinators, but the plant doesn’t grow invasively. Another option is to keep common lilacs (Syringa vulgaris), which are famed for their oversized purple and white flowers and their fine fragrance, and they aren’t known to grow invasively.

4. Swap blueberries for burning bush.

Burning bush is one of the flashiest shrubs you can find, thanks to its bright red autumn leaves, which are so vividly colored they look like they’re on fire. But like the other invasive plants on this list, burning bush is an aggressive grower, and it can spread over gardens and wild landscapes and make it hard for other plants to take root. Worse still, burning bush plants spread prodigiously via seeds, which are typically sown by wild birds!

But if you want to enjoy shrubs with bright red leaves but don’t want to sacrifice your garden space to noxious invasives, common blueberry shrubs can be a surprisingly perfect substitute. Although lowbush blueberries are short plants that are most commonly used as groundcovers, highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) are taller specimens that can grow up to 15’ tall, and they have bright red leaves in autumn and even brighter red stems in winter!

Aside from adding color to autumn gardens, blueberries are relatively easy plants to grow, especially if you have acidic soil. Plus, these plants bloom prolifically in spring and their bell-shaped, white flowers attract bumblebees. And, of course, blueberries are edible and delicious too!

For even more options, you may want to try out fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), which is a native plant that’s ultra colorful in autumn. Fragrant sumac also functions as a host plant for spring azure and red-banded hairstreak butterflies.

5. Swap chokecherry for Chinese privet.

Chinese privet has traditionally been used as a privacy shrub, and its fast growth rate helps it fill in empty spaces in lawns and landscapes. Prized for their glossy leaves and fragrant white flowers, Chinese privet plants also have a lot of ornamental appeal. But their aggressive growth rate makes them problematic, especially in wild areas where they can rapidly take over.

But the good news is that there are several fetching ornamental plants that can be grown in place of Chinese privet. Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) is one popular choice for wildflower gardens as chokecherry is native to many areas of North America, including parts of Canada and the eastern and central United States. A fast grower, chokecherry can be used to add privacy to outdoor spaces, but it won’t cause the same issues as privet, and it has bright red berries that wild birds can’t get enough of.

If you aren’t fond of chokecherry, another native plant option is inkberry (Ilex glabra). Hailing from the eastern and south-central United States, inkberry’s shiny leaves look quite similar to privet, but this plant has inky dark berries, which give it a bit of added drama. Plus, inkberry plants can grow in sun or shade, and they serve as host plants for the Henry Elfin’s butterfly.

6. Swap American wisteria for Chinese or Japanese wisteria.

Chinese and Japanese wisteria are commonly grown on arbors and fencing, and they’re known for their climbing growth habit and rapid spread. But while these wisteria plants can be used for extra privacy, most growers choose Chinese or Japanese wisteria plants for their trailing, lavender-toned flowers that put on a showstopping display when they bloom in spring.

However, when these wisteria plants are added to gardens, they sprawl all over the place, choking out smaller plants and even pulling down trees. Dramatic as that is, there is another option: native American wisteria (Wisteria frutescens) plants. These plants look just like Chinese or Japanese wisteria, but they don’t grow as aggressively, and they’re host plants for at least 17 different species of moths and butterflies!

For even more vining plant options, you can also try out Dutchman’s pipe (Aristolochia macrophylla) or crossvine (Bignonia capreolata). These plants don’t have quite the same look as wisteria, but they’re highly attractive to pollinators, and their unusual flower forms can make them stand out in a crowd!

7. Swap Virgina rose for beach rose.

Beach roses are commonly planted in beachside gardens due to their high salt tolerance. But these durable plants are also grown for their oversized, pinkish-purple flowers and their large, edible rosehips that are harvested in fall to make rosehip jelly and other sweet treats. Unfortunately, beach roses are also invasive plants, and when birds eat their rosehips, these plants can be quickly spread to wild areas where they take over.

Despite their ubiquity in the United States, beach roses are actually native to Asia. However, there are native American roses that have the same colorful look as beach roses but without their invasive tendencies. And, of course, since all roses produce edible rosehips, you won’t need to sacrifice your rosehip jelly if you grow these plants either!

Virginia roses (Rosa virginiana) and swamp roses (Rosa palustris) are both native to North America, and they can be used in the same way as beach roses in landscape designs. Grow these plants in a hedge for privacy, or keep them as specimens in your edible garden. It’s up to you!

8. Swap crossvine for wintercreeper.

Wintercreeper does flower, but most growers cultivate this plant for its colorful leaves that are commonly streaked with shades of gold and green. Often grown as a groundcover, wintercreeper can also be allowed to climb, and when plants are happy, wintercreeper vines can spread over 70’! While this is useful for garden privacy, wintercreeper can be invasive in some areas, and it can pose a lot of trouble for other plants in your garden, as well as plants in the wild.

Due to its invasiveness, many gardeners may want to skip wintercreeper entirely, but there are plenty of alternative plants to try instead. If you were drawn to winter creeper for its vining tendencies, you may want to experiment with crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), which has large, trumpet-shaped flowers that are always a hit with pollinators. Even better, crossvine is native to North America, and its dense leaves provide habitat for birds, squirrels, and other critters too.

On the other hand, if you like the dual use of wintercreeper as both a vining plant and groundcover, Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) may be an even better option. Wintercreeper can be allowed to grow over the soil for weed suppression, but it’s equally happy clambering up walls and fences. This plant also serves as a host plant for sphinx moths, and its leaves turn a flashy shade of crimson in autumn as well.

9. Swap Virgina creeper for English ivy.

English ivy is sometimes grown as a groundcover or a climbing plant, and it’s easily recognized by its palmate leaves that feel a bit leathery to the touch. As classic as English ivy looks, this plant is a vigorous grower that can scramble up trees and pull them down with its weight. On top of that, English ivy is known to choke out other plants, and its sturdy roots can even damage masonry if it’s allowed to climb up trees and fences.

With all of those issues, it’s no wonder why more and more gardeners are looking for less invasive alternatives to English ivy. And the good news is that there are lots of plants to choose from.

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is one solid choice that can be grown in any place where you’d normally sow English ivy. Unlike English ivy, Virginia creeper uses adhesive pads to climb, so it is much less likely to cause issues with buildings. But you can also try out wild ginger (Asarum canadense), which doesn’t climb but it does grow beautifully in shady spots, and its round leaves have the same glossy and leathery finish as English ivy.

10. Swap buttonbush for autumn olive.

Autumn olive is sometimes grown as an edible, but it’s also cultivated for its fragrant flowers that appear from April to June. However, like other plants on this list, autumn olive can be spread into the wild by birds, and once it arrives, it can outgrow many native plants.

Instead of keeping autumn olive in your garden, why not grow other edible landscaping plants, like raspberries, blueberries, or cherries? Or try some chokecherries in your yard instead. Like autumn olive, chokecherries can be grown as ornamentals, but they also make tasty jams and jellies, and wild birds love them, too.

Alternatively, buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) can be a fun plant to try. This plant has lots of whimsy thanks to its adorable, spiky white flowers, but it’s also a hit with pollinators. In fact, buttonbush shrubs act as host plants for at least 25 different species of butterflies and moths, including promethea and tussock moths.

11. Swap Pennsylvania sedge for lilyturf.

Lilyturf is popularly grown as a groundcover or border plant, and it can add a lot of color to gardens with its variegated, grass-like leaves and tall, purple flowers. Unfortunately, lilyturf also grows as an invasive in some areas, particularly in warmer spots. When allowed to spread via its underground rhizomes, lilyturf can form dense mats of leaves, which are hard for other plants to penetrate.

If you don’t want to tangle with lilyturf, many native grasses, sedges, and rushes can be used in your garden instead. With its large seedheads, Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica) is a particularly attractive native plant option, and it can provide habitat for many native insects and animals, too. For a more colorful look, try out creeping phlox (Phlox stolonifera), which blooms prolifically in spring and creates dense carpets of pink and white flowers that pollinators can’t get enough of.

12. Swap clumping bamboo for running bamboo.

Bamboo has a lot of charm, and it’s hard to beat when it comes to providing garden privacy. But running bamboo can be a tricky plant to manage, and it can quickly take over small gardens and spread into the surrounding landscape. Once in place, running bamboo can be hard to eradicate, and some types of running bamboo can grow over 30’ tall.

Unlike running bamboo, clumping bamboo plants are less likely to go haywire, and they grow in tidier clusters that pose much less of a headache for gardeners. If you’re tired of tangling with running bamboo, you may want to try out clumping bamboo varieties instead. Or, if you simply like the natural look and segmented stems of bamboo, you can experiment with native plants like the common rush (Juncus effusus) instead!

Frequently asked questions

What does it mean if a plant is invasive?

Invasive plants are plants that aren’t native to your local ecosystem. But more than that, invasive plants are plants that are known to grow aggressively, and they may cause other problems in gardens and the wild as well. Most invasive plants outcompete native plants, but some invasives can also change the composition of soils and make it hard for other plants to grow.

Has an invasive species ever been good?

The tricky thing about invasive plants is that many of them have spread into our environment because they have provided some use for humans at some point in time. Many plants that are known to be invasive now were previously coveted for their beauty or because they’re edible and tasty (such as garlic mustard.) However, it’s important to weigh the pros and cons of the plants you’re growing, and, in the case of invasives, there are typically so many negatives associated with growing them that intentionally planting them is just not worth the risk.

What is the best way to remove invasive plants from the environment?

If invasive plants have invaded your garden, there’s no reason to reach for chemical herbicides. Instead, most invasive plants can be managed by regularly pulling them up or cutting them back by hand. Once they’re gone, be sure to cover up empty soil in your garden with mulch, weed barrier fabric, or fast-growing native plants so invasives can’t regrow.

How are invasive species transferred?

Many invasive plants were once intentionally planted as ornamentals or edible food crops in gardens. But once they enter into landscapes, invasive plants can be spread into the wild by the activity of birds and other wildlife. Some invasive plants spread via windborne seeds, while others grow rapidly through underground runners, and some invasive seeds can even hitch a ride in the treads of your shoes or tires.

Can invasive plants harm humans?

We live in an interconnected world, and what occurs in our environment affects us indirectly and directly. When invasives invade, they can reshape ecosystems and change the way humans and animals move across landscapes. Some invasive plants, such as English ivy, can also damage masonry and pavement and cause costly problems for homeowners.

Why are native plant species important to an ecosystem?

Native plants are the plants that naturally grow in our growing regions, and as such, they are perfectly suited to the needs of native pollinators. More than that, native plants are well adapted to our local climate patterns, so they typically need less water and maintenance than nonnative species. Many native plants serve as host plants for insects, and studies have found that pollinators are up to 4 times more likely to visit native plants than other flowers.

Summary

When invasive plants first made their way into the gardening world, most people had no idea the effects these plants would have on our landscapes. But after years of trial and error, we now know that invasive plants can cause a lot of problems for native plants, native animals, and people as well. But by swapping out invasive plants for natives and slower-growing ornamentals, we can reverse a lot of the damage invasives have caused throughout the years and prevent these troublesome plants from creating issues in the future.

For more tips on organic invasive plant management, read our guide on the most common invasive plants you may encounter in the wild or in your garden. And you may also enjoy our guide on the benefits of growing native plants.

Leave a Reply