“Though the weather forecast is not ideal, we will go ahead with the Midland Empire Audubon Christmas Bird Count tomorrow,” the email read.

Not ideal was right. Earlier in the week, it had been warm and comfortable outdoors. Now, the evening before the big Audubon bird count, the weather turned drizzly and cold, and the wind was stirring the branches.

“Do what you can to cover your territory, but feel free to modify your plans accordingly,” the email continued. “Sites sheltered from the wind on the south & eastern sides of levees, hillsides, riverbanks, groves of evergreens, etc., especially with nearby food and water, can often be more productive on these kinds of days.”

It has been worse – the coldest day was in 1981 when temperatures dropped to -20, and the ground was covered in snow. The second coldest was 1989, when it was well below zero.

Read more: Seed-Bearing Plants to Grow for Wild Birds

The day of the bird watch dawned gray with a light drizzle. Gray everywhere – gray sky, gray rain, lousy visibility, and the skeleton-black trees swayed in the cold wind.

I wore my insulated overalls, Carhartt coat, and work boots from when I worked at the Parks department, but I had forgotten to bring a waterproof hat. My gloves were not waterproof either and I wished I had some Thinsulate gloves. Well, we would just have to endure.

Jump to:

About the Audubon Christmas Bird Count

So why were people all excited about going outside in a cold drizzle on this particular day? I mean, these are birders, but still!

It’s because the Audubon Christmas Bird Count is one of the largest bird counts in North and South America and around the world. The bird count started in 1901 as a backlash against the annual Christmas bird hunts wherein hunters would go a-shooting to see how many birds they could kill.

These days the Christmas Bird Count has become a census for birds across the nation and across some areas across the world. Read more about the Audubon Christmas Bird Count.

Learn about 6 DIY Ornaments to Create for Feeding Wild Birds This Winter

Why is the Audubon Christmas Bird Count So Important?

First of all, researchers use the bird count to increase their understanding of the health of the bird population across the United States and the Americas.

These bird numbers go back to 1901, and with this information, researchers have determined that a lot of bird populations have been declining.

However, some bird populations have increased due to efforts to restore wetlands and increase habitat across the nation. As a result, the number of waterfowl, such as ducks and geese, has grown.

So meaningful change can happen. We just need people to do this on behalf of songbirds as well as all birds.

Read more: 12 Tips for Creating a Winter Bird Habitat

Habitat loss has been a great blow to bird populations throughout the United States. In my area, we used to have windbreaks around houses and wild areas along every fence row. Streams and rivers in those days were still surrounded by trees. There used to be long strips of trees, shrubs, and grasses along the edges of every field – a habitat for animals and birds.

Now, as farming has become more mechanized, most of these habitat strips were bulldozed in order to “increase yields.”

We used to have lots of bobwhite quail here, and their “bob-WHITE” calls were common in the 1980s and into the 1990s. We had pheasants, too. One morning in the early 1990s, I was driving to college when a red-necked pheasant shot past my windshield. I just about drove off the road, so I could miss it!

It’s been a long time since I’ve heard a bobwhite call or seen a pheasant here. I would love to see farmers, landowners, and homeowners create habitats for wild birds and animals again.

Cruising for Birds

I met the other birders in the parking lot of the Worthwine Island Conservation area, and they invited me to drive around with them in their nice, big, warm truck. I appreciated this very much because it was 38 degrees outdoors but felt colder due to the strong winds.

The birders had been doing the Christmas Bird Count for decades with the local chapter of the Audubon Society, so they had the drill down.

Our local chapter was covering a 15-mile-wide circle that had been divided into 20 sections. We were working in Section 9, so we drove from place to place to get a general count of birds. We started in the conservation area, then traveled to the river, a nearby small town, and to various cemeteries where birds were thick.

Anytime a bird popped out of the grasses or a flock passed overhead, we’d stop and pick up our binoculars. We would identify the birds and count how many we saw. If the birds were in a large flock, we’d make a rough estimate. Then Carol would write the information down on a sheet of paper, along with the place where they’d been spotted.

We were basically taking a bird census, so we needed these numbers to be as accurate as possible.

A Slow Day for Birds, Unfortunately

The weather worked against us as far as getting a nice count of birds. The birders told me that every year, they’d been able to spot a northern harrier that lived near the levee. (A northern harrier is a very handsome little hawk that shows a patch of white just above its tail when it flies, which makes it easy to identify.) But this year, though we looked eagerly, our harrier opted to stay in hiding.

Even the Missouri River was devoid of bird life, probably to the frustration of several duck hunters who were hunkered down nearby.

I did see four very pretty Canada geese sitting in the river that were nearly added to the list before Carol pointed out that they were decoys. I didn’t notice that the geese were not moving!

A few times, we got out of the truck and walked around some spots with good bird habitat – food, water, and cover – to see if we could scare up a few species that had been hidden away from the road. Even then, we weren’t able to come up with much.

A New Way to Identify Bird Calls in the Field

If you spend any time birding, you know that birds can be notoriously shy, especially if they’re a species you want for your life list. On this windy, cold, freezing, drizzling gray day, they were hunkering down (who can blame them?) but still talking,

I used the Merlin bird app to verify bird species, and to find any hidden birds that were not showing up in our binoculars.

Sparrows are tricky to see in the field, especially on a cold day. Their songs, as far as I'm concerned, all sound the same.

The Merlin app was able to identify the different sparrow songs and showed which birds were calling, and the seasoned birders were able to ID them visually.

Read more: 10 Tips to Attract Cardinals to Your Bird Feeders This Winter

I cannot say enough good things about this app. I usually don’t like to talk up newfangled computer thingys, but this app is run by Cornell Lab of Ornithology at Cornell University, and they’re not trying to sell you anything. It was originally set up to help birders identify birds in the field – which it’s good at. The app is able to identify 6,000 birds worldwide.

These days, the Merlin app does even more. The information that you gather on the birds – sightings, bird call recordings, and photos – can be submitted to eBird, where you can build your life list, find where the rare birds in the area are being spotted, and contact local birders. The data it collects on birds worldwide can be used by scientists, researchers, and birders alike. And both programs are free!

Identifying Stealthy and Hidden Birds

We stopped at a bridge on a gravel road because there were huge numbers of birds there, so we started identifying them via binoculars. I set my phone down to record bird calls via the Merlin app. The birds were busily calling – juncos, cardinals, a couple of tufted titmouses, a nuthatch, goldfinches, song sparrows, and even a Carolina wren from a house up the road.

The Merlin app showed me that there were also many white-throated sparrows singing. The “chip” sounds they made were quiet, and I would not have noticed them if they hadn’t shown up on the app. I looked at where the calls were coming from but couldn't see the sparrows, so I walked off the road to get a closer look.

Just then, a few small brown birds flew low from a strip of foxtails into a nearby row of brush. They were too quick to discern more than the fact that they were sparrow-shaped. A few more zipped past. These little birds were too stealthy to let us identify them! But as the sparrows flew to the underbrush, the white-throated sparrow “chip” sounds started coming from the places where they’d flown to. So that allowed me to get a positive ID.

Wherein I Find Some Really Cool Birds

After lunch, I went alone to the place where I’d started and walked through the grasses as the wind blew a light drizzle over everything. Earlier, I’d noticed a number of little sparrows hiding in the grasses, and now I wanted to get a closer look.

Now and then, a song sparrow would pop up to the top of a dead prairie plant as a sentinel and eye me, warn her fellow birds about the interloper, and then drop back into hiding.

Read more: 12 Best Heated Bird Baths for Your Winter Garden

A song sparrow was calling with a little “chip” call. Then another sparrow joined in – a swamp sparrow. They were having a conversation, talking back and forth. The song sparrow gave a high-pitched “chip” call, and then the swamp sparrow replied with its lower “chip.” Swamp sparrows are rarer in this area, so I was all abuzz.

Then, as I carefully crept through the grasses, a wren exploded into song next to me for a few seconds – a winter wren! My eyes got big, and I looked around for her, but she didn’t make another sound. What a find!

Tabulating the Bird Count Results

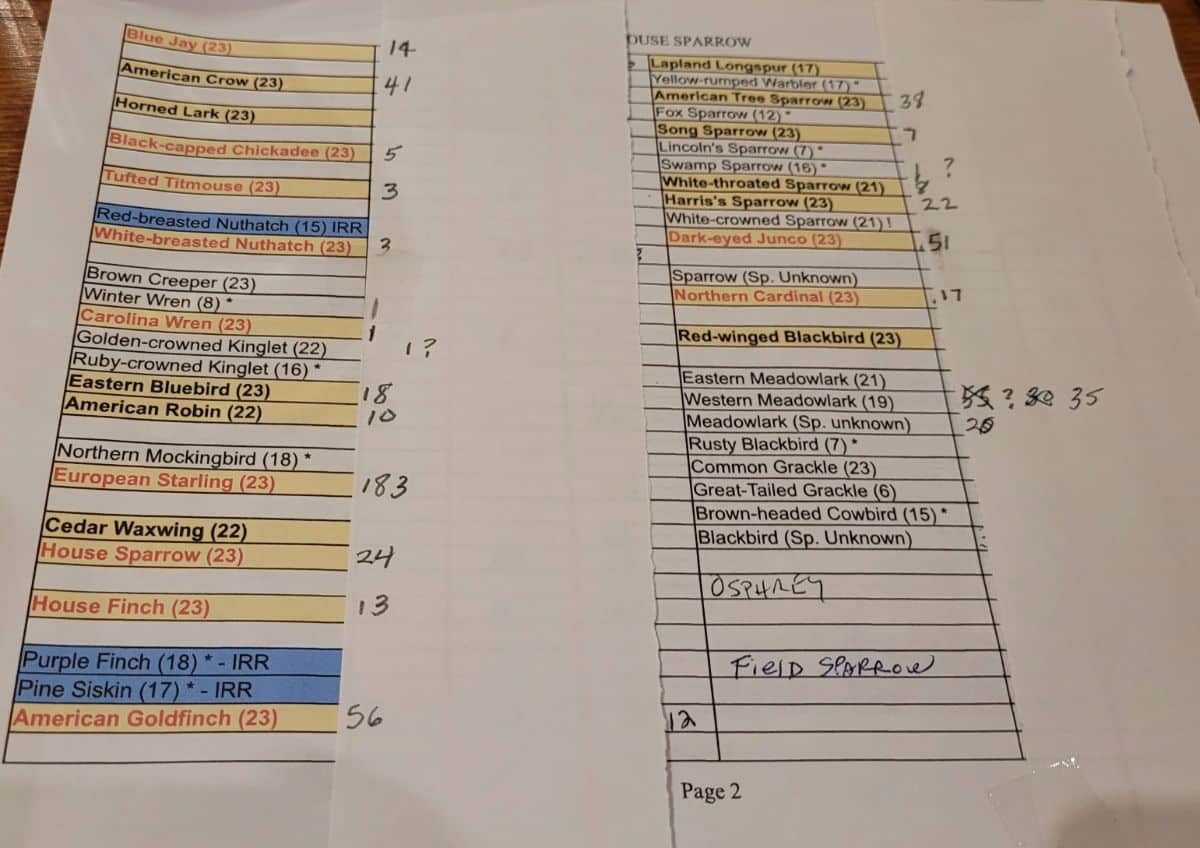

That evening, our group of hungry birders gathered at a local restaurant with their lists and bird counts to compile what they’d found. We ate supper and talked about what we’d seen out in the field. All of us were disappointed in our overall numbers, but many had been able to spot some impressively rare and uncommon birds.

After supper, our count coordinator went through the list of area birds with us and wrote down our totals for each species. Once he compiled the complete lists from all the participating birders in our area, he would send the finished tallies to the Audubon Society, along with photos and recordings necessary to verify birds that were rare and uncommon in our area.

The next day dawned sunny and bright and windless. Birds were everywhere – of course! Flocks of robins filled the trees, and birdsongs rose from all directions.

But that’s okay. Despite the drizzle and wind, we still had a good time. I’m looking forward to doing this again next year – and I’ll be searching for prime birding spots!

The Audubon Christmas Bird Count is still going on. Contact your local Audubon Society for more information.

If you aren’t able to participate this year, the Great Backyard Bird Count will be taking place from Friday, February 16, through Monday, February 19, 2024. Participants will count and report birds in their own backyards.

Leave a Reply