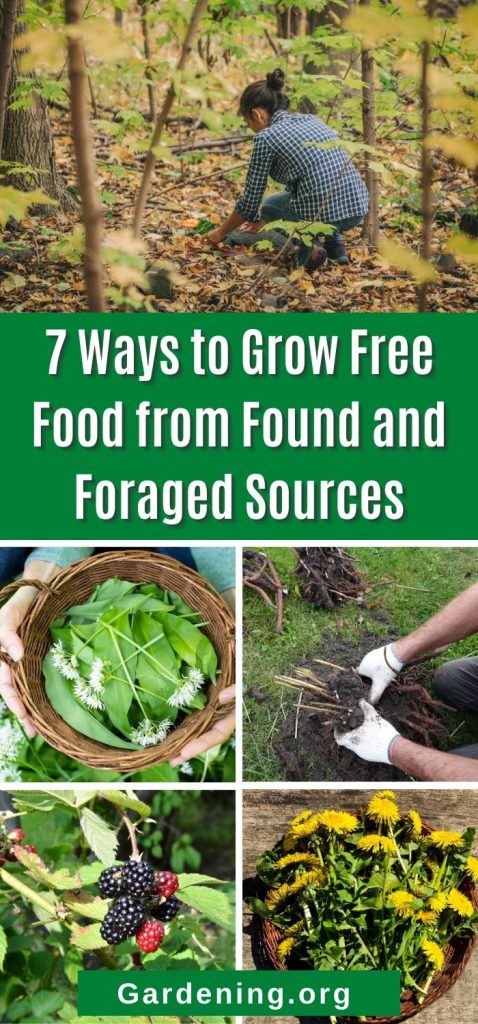

There are many things that can be grown for free from found and foraged sources. Rooting and planting from wild trees, plants, and bushes is an excellent way to grow a lot of variety, start a home fruit or berry orchard, and increase your personal food resources. If you are growing a survival garden or garden for self-sufficiency, found and foraged plants are an excellent free, locally adapted source of food plants.

Jump to:

- Forage for Free Food Sources

- Find Free Food Sources

- Methods for Growing from Found and Foraged Foods

- 1. Grow from found or wild seed.

- 2. Grow from cuttings.

- 3. Grow from shoots.

- 4. Growing from grafts.

- 5. Growing from splits and divisions.

- 6. Growing from transplants.

- 7. Check your pantry.

- Patience is a Virtue

Forage for Free Food Sources

If you can find and positively identify wild fruits and vegetables, you can use that wild bounty to grow more for yourself on your own property. After all, today’s commercial seeds and plants once started out as something in the wild that grew in popularity and were shipped and transplanted to places all over the world.

Everywhere in the world has some native foods, fruits, and berries. There are many ways to grow these free natural resources for your own use. You can do this with little to no impact on the plants, too. Just a seed, root, or cutting is all it takes.

The key to safely using wild and foraged sources for food crops is to positively identify the trees, plants, or bushes you are scavenging from. It’s smart to start with a plant identification app (Picture This is one such app, but there are many).

It is wise to cross-reference that result with a local guidebook and also by confirming your find with a knowledgeable local person, if one is available to you. If you do not know anyone with good knowledge of local wild plants, take good pictures of leaves, buds, blossoms, bark, and roots (if possible) and post them to a trusted online social media group or forum.

Of course, make sure you have the permission of the landowner if necessary before removing plants or parts of plants.

Find Free Food Sources

Foraging refers to plants, trees, and food that you can find in the wild. When we talk about “found” sources, we’re talking more about plants that are growing in another person’s yard or garden, which they may be happy to let you have a piece of to grow your own.

People will often be willing to give free pieces of perennial food crops when they are dividing them or when they are becoming large and overgrown. If you have something to barter or trade, even better.

Ask friends and neighbors or ask on local buy nothing/free websites for any food plants that people might have and are willing to give away. Watch the groups in the spring and fall when people tend to be cleaning out old garden beds, thinning, splitting, and moving plants. Often, people just want the old things to go away; and one man’s “trash” could be your garden treasure.

Methods for Growing from Found and Foraged Foods

There are different ways to grow new plants from found and foraged resources. Some plants are more suited to propagating or growing from one method over another. Let’s look at the different methods you can use and see a few examples of plants that would be well-suited to each.

1. Grow from found or wild seed.

Growing from seed is the method that is most well-known to people. Growing wild plants from seed isn’t a lot different than growing purchased seeds. There are some exceptions. For example, many wild seeds will need you to mimic and recreate the natural conditions they grow under, so they may require things like a dormant period or a cold stratification period to sprout. The information isn’t hard to find if you do a simple online search for how to grow the seed in question.

Strawberries, blueberries, blackberries, elderberries, and fruits are good examples of things you can forage in the wild and grow from seed. Seeds of dandelions, lamb’s quarter, and other “weed” seeds are also good examples. Wild herbs and flowers (which are often edible) are prime for starting from seed. Generally speaking, you’ll want to collect the seeds after the plant has completed its annual cycle and when seeds have dried down and hardened.

Starting plants from seed is the slowest route for most things—especially for larger plants like trees and bushes, and for anything with a woody trunk or stem.

2. Grow from cuttings.

A cutting is just what it sounds like—it is a piece of the plant cut off, then rooted and regrown into a new, separate plant or tree.

Cuttings can be taken without the plant hardly even noticing (as long as you don’t take too much of the plant). In fact, it’s often beneficial for the plant to have some cuttings taken because it stimulates new growth, relieves it of some of the overgrowth it is feeding, and can help synchronize the growth, blooming, and production cycle of its food crop.

Cuttings can be taken as green cuttings (such as when new spring shoots are sent up on woody-stemmed plants before they get their woody bark). Green cuttings will typically root quickly in water (but do know that sometimes they have a harder time transferring into soil).

Cuttings can also be taken from the hardened woody stems of plants. Woody cuttings can also be rooted in water, but they will usually do better in well-watered soil (kept moist and not allowed to dry out while roots are establishing).

Dipping cuttings in rooting hormone can speed and encourage root growth. It’s good insurance and a good boost for not much money. Some plants that root more easily than others, like elderberries, don’t necessarily need this step, but it can’t hurt. Some natural rooting “hormones” that you can use instead include honey and willow water.

Cuttings are often made when dormant plants are pruned—or can be. If you know someone that has a type of bush or tree that you want to grow, ask them if you can take a cutting or take some of their pruning waste off their hands.

How to root cuttings

When rooting cuttings, you want to make sure you have at least two to three sets of leaves or leaf nodes. The bottom one or two sets should be stripped and then sunk into the ground (if rooting directly) or into a deep pot of potting medium or soil. The leaf nodes that are below the soil line will grow into roots instead of leaves and new shoots will eventually emerge and break through the soil line.

One thing worth noting is that the top leaves of rooted cuttings often die off after some time because they’ve lost their root support. This does not mean the cutting has failed or died. Give the cutting some time (as long as eight weeks) of good maintenance before you decide it hasn’t taken. As with anything, not all cuttings succeed so it is smart to start more than you really need to grow for your food source.

Cuttings can be taken from wild plants just as easily as from propagated or yard plants. There’s no difference in the method, just in where you get your cuttings from. You’re not usually harming the wild plant and in fact may be helping it because wild plants are not usually pruned, trimmed, or maintained.

Cuttings are easy to take and easy to plant. They take less time than growing from seed and can give you a jump of an entire season or more.

Almost any woody berry or fruit bush can be regrown from cuttings. This is, in fact, the most recommended and most common way to grow elderberries among commercial growers—cuttings are cheap, easy to ship, and easy to establish, and an entire field can be planted with virtually no digging.

3. Grow from shoots.

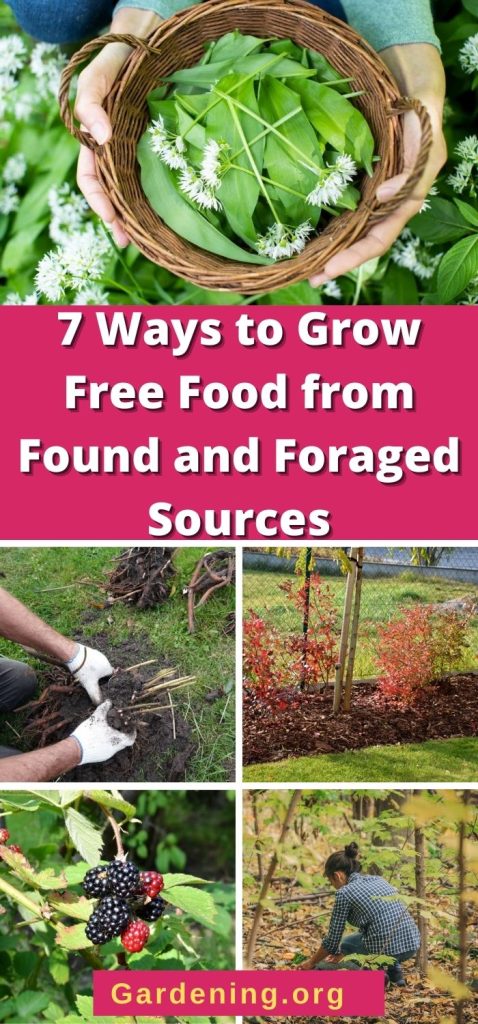

Some plants, berries especially, spread naturally by sending out shallow roots that grow upwards into shoots. They radiate out from the bottom of the mother plant and if you dig back far enough, you can find a trail of attachment back to the plant’s root crown (but you don’t need to do this).

These shoots can very easily be chopped at a point in between, dug, and then replanted to establish new plants of your own. Most plants and bushes that send shoots do not have very deep root systems at the shoot, so it’s not hard to do (and can often be done by hand).

Just make sure that when you dig your shoots, you get some strong, well-established root with it. Again, it’s not usually very difficult to find and pull or dig the taproot of the shoots and just stab into the ground to cut the trailing root to separate it from the parent plant.

Elderberries are an excellent example of a plant that spreads via shoots and whose shoots are easy to dig and reestablish. Blueberries also spread from a root crown in this way. Blackberries, raspberries, and other brambles also spread via shoots and are easy to divide and regrow.

Because the roots are already established on shoots, they are generally quick to establish when replanted. Replanting shoots is usually faster than growing from seed or cuttings.

4. Growing from grafts.

Grafting is similar to rooting but is a little more involved. Grafting is when you take a cutting, usually from a tree, fit it and tape it onto root stock from a different (but related) tree. To do this, you will need some materials and you will need root stock. Root stock can be purchased from orchard suppliers and nurseries but is often only available seasonally (during grafting and pruning season).

Grafting is the most common way to propagate fruits like apples, peaches, plums, and others. Think orchard trees. Grafting speeds the process for these trees that don’t tend to root as well as smaller plants like berry bushes. It also ensures that the new tree and its fruit will be true to type. If you were to grow an apple from seed, not only would it take a long time until it became productive, but you couldn’t be sure what tree it was pollinated with and so the fruit might be different than the tree the seed came from.

Grafting, while more involved, is an option but is a more difficult option with a steeper learning curve and more specialized supplies needed. It does, however, take years off the process of establishing a new fruit tree.

5. Growing from splits and divisions.

Some perennial vegetables and plants grow from a root crown. These plants can be dug up, lifted, split and divided (using a knife or a sharp spade shovel). The original plant can then be reseated and re-covered, and the divided pieces can be grown elsewhere into new plants.

Common examples of plants that grow this way and which you can grow for free are rhubarb, asparagus, and horseradish. There are places where these plants grow in the wild, too.

Don’t worry that you are damaging or undermining the parent plants by taking divisions off them. In fact, you’re doing the parents a favor. After about three years, these plants tend to get root bound and their productivity decreases. The way to get it growing strong again is to regularly divide the plant every few years and stimulate new expansion and new growth.

Dividing is an important part of maintaining a strong bed of rhubarb or asparagus. It is also beneficial for plants like horseradish and many spreading herbs—mint, chives, marjoram, oregano, and their relatives for example.

Wide-spreading plants can get very invasive, so it’s often in the best interest of the gardener to dig out some of these spreaders to keep them in check. Even strawberries need to be thinned to keep the plants large, productive, and to give them room to breathe. Often the unneeded divided pieces go onto the compost pile.

If you know anyone with any of these types of plants, let them know you’d be interested in some divisions. Offer to help them dig and divide when they’re ready, and you’re quite likely to get your plants for free!

6. Growing from transplants.

You can also grow food for free from found and foraged transplants. There are many plants that we commonly think of as weeds that grow in the wild, but that are very good, nutritious foods if you learn how use and prepare them. If you have these wild food weeds around you, or if you are weeding them out from a place you really don’t want them to grow, you can easily dig them and transplant them somewhere else.

Some examples of wild edibles you might want to establish in your food beds include dandelions, lamb’s quarter, purslane, chickweed, curly dock, wild asparagus, ramps, fiddlehead ferns, plantain, and many others. Do check before digging or removing wild plants to make sure that they are not protected in your area (in fact, this is true for all these growing and propagation methods and varies in different locations).

7. Check your pantry.

Though not exactly foraged, and probably not exactly free, you might “find” that there are things in your own home pantry that can be planted and grown, too. For example, dry peas and bean seeds can be planted just like purchased seed. Potatoes and sweet potatoes can be grown into new plants. Whole herb seeds can be grown, too.

Though you likely bought and paid for these items. You'll only need a fraction of what you bought to grow more. You can grow so much from so little that it’s almost like free—especially since you’ve gotten the benefit of using it as a food source already.

Patience is a Virtue

You may have noticed that several plants can be propagated in more than one way. For all of them, be prepared with some patience. It takes time to establish new plants. For many perennial food plants, especially fruits and berries, don’t expect a harvest in the first year or two. Do know, though, that the sooner you do start, the sooner you can harvest. This is just as true when you are planting new trees and plants that you buy—only without the expense!

Leave a Reply