Blossom end rot is a very common problem in home gardens. It seems that everyone knows the cause – a lack of calcium in the soil.

But that’s not exactly true. This is why adding calcium from things like ground up egg shells, bone meal, or even calcium-based antacids doesn’t work most of the time.

So what’s the real story? What are the most likely causes of blossom end rot in garden vegetables?

Jump to:

- First, What Vegetables Can Suffer from Blossom End Rot? (It’s not just tomatoes)

- What Blossom End Rot Looks Like

- When will you usually see BER?

- BER Can Be the Cause of Secondary Diseases

- It’s True that Low Calcium is the Cause of Blossom End Rot

- BUT! Soil Doesn’t Usually Lack Calcium

- But you can test to find out if yours does!

- Uptake and ACCESS Are the Real Calium Problems for Plants with Blossom End Rot

- Three Top Causes of Blossom End Rot in Vegetables

- 1. Too Much Water

- 2. Not Enough Water

- 3. Overfertilizing

- Other possible causes of Blossom End Rot:

- Better Tips for Preventing Blossom End Rot in Garden Vegetables:

- What You Can Do to Immediately Correct Blossom End Rot in the Short Term

First, What Vegetables Can Suffer from Blossom End Rot? (It’s not just tomatoes)

When we talk about blossom end rot, people usually think about tomatoes.

Tomatoes are not the only garden vegetables that suffer from blossom end rot.

Other garden vegetables that frequently fall victim to blossom end rot, or BER as it is often referred to, are:

- Peppers

- Squash

- Melons, including watermelon

- Pumpkins

- Eggplant

What Blossom End Rot Looks Like

Blossom End Rot is fairly simple to spot.

- It occurs on the blossom end of the fruiting body (fruit or vegetable)

- The lesions start as very small spots. Usually, the early spots go unnoticed until they get larger

- Spots are typically dark, but early on, they may be light and look similar to blight but occur near the blossom end

- As the fruit matures and grows, the spot will, too. It can become half or more of the fruit

- In very early stages, you may not be able to see BER on the outside of the fruit, but if you cut into it, there can be dark or black, mushy, mealy flesh inside the vegetable

- Spots look “watery” and soft in the early stages, and later will look tough and dried out as cells break down behind the skin

- Lesions are described as “leathery” looking; they are usually brown and may appear shiny

- Lesions may range in color from brown to black, green, and yellow

- Soft spots form in the fruit or vegetable where the BER is

- Lesions will be opposite of the stem end (because this is the furthest distribution point and the last to get the calcium that the plant does uptake)

- This can look more like flat-out rot or mold in different types of vegetables, like on summer squash and zucchini

- On peppers, BER resembles sun scald or sunburn

When will you usually see BER?

Blossom end rot is more common in the first fruits a plant produces. These grow at a time when the plant is often still actively growing and calcium is more in demand. Fruit and vegetables get calcium last, so when the plants have limited access, they will suffer first.

- It is not uncommon to experience BER in the first set or two of fruit, and then it can clear up and go away.

- If you deal with the cause of blossom end rot early, you can save your vegetables and still net a great harvest.

BER Can Be the Cause of Secondary Diseases

Mold and secondary rot and disease can set in at the wound site, too, because there is already damage, and the fruits are lacking in the nutrients they need.

If you see soft, rotting fruit or vegetables or symptoms of fungal disease or mold near the blossom end, this is often the result of adventitious diseases that found a way in.

This is something to keep in mind when you are diagnosing and treating your plants. Even if what you’re seeing doesn’t look exactly like BER, it could be a secondary effect of the presence of BER.

If fungal diseases and molds appear, it’s smart to treat the whole plant with a good, organic antifungal treatment like Neem oil.

Sometimes, the conditions that led to blossom end rot (like too much rain and moisture) go hand in hand with fungal diseases like blight and with mold and mildew. Treating with a low-impact antifungal agent is easy, cheap insurance.

It’s True that Low Calcium is the Cause of Blossom End Rot

If it’s been drilled into your head that blossom end rot happens because the plant is low in calcium, you’re not alone. This is what most people learn. In fact, it’s true in a way.

A deficiency in calcium is what causes blossom end rot. But there is more to the story.

BUT! Soil Doesn’t Usually Lack Calcium

Most soils do not actually lack calcium. Most soil has more than enough calcium in it. Over the years, people have come to believe that you should add more calcium to your soil if you have blossom end rot.

But that doesn’t usually help because the calcium is there; it just isn’t getting to where the plant needs it. There are reasons for that.

- Note: adding calcium to your soil won’t hurt, but you probably won’t see an improvement, either.

- This is because low soil calcium is probably not the problem.

But you can test to find out if yours does!

It’s not common, but it is possible that your soil is low in calcium. So, it’s not a bad idea to test the calcium level in your soil. This is especially helpful if you have tried other solutions to BER or if it comes back and plagues you year after year after year.

A simple soil test will tell you if your soil has enough calcium. You can get a home soil test kit or send it out to a local lab, college, or university test center.

If it does turn out that your soil is actually low in calcium, you can easily amend it. Bone meal, lime, and other DIY amendments like wood ash and eggshells are all options.

This is a good future solution, but you’ll usually notice blossom end rot during the growing season. There are things you can do then, too – and it starts with understanding the real, more common reasons BER crops up.

Uptake and ACCESS Are the Real Calium Problems for Plants with Blossom End Rot

There is probably adequate calcium in your soil. Odds are your soil has more calcium than what your plant needs. They just can’t get to it.

The bottom line is this: Blossom End Rot is not usually an issue of calcium availability. It is usually an issue of calcium access. Uptake.

The problem, more often than not, is that something is stopping your plants from being able to take up and move calcium throughout the plant to where it needs to be.

- The bottom of the fruit or vegetable – which is the end where the blossoms are – is the last to get calcium.

- When it isn’t available for whatever reason, that’s where the problem sets in and deformation in the form of blossom end rot takes place.

Three Top Causes of Blossom End Rot in Vegetables

If you want to stop blossom end rot, correct it, or prevent it, you need to know what the most common reasons are that calcium doesn’t get from the soil to the blossom end.

Three things are most often to blame. Usually, it’s one of the first two.

1. Too Much Water

Watering problems are the real cause of calcium end rot most of the time.

- Too much water dilutes calcium concentrations and flushes calcium through and out of the plant and its fruit rather than giving it a chance to stay and build up plant tissue the way the plant needs it to.

- Too much water also impacts how the plant takes it up, and even though water is there, it may not be moving through the plant and moving those nutrients efficiently.

- Too much water also causes root rot problems, damaging the access ports for water, calcium, and nutrients.

2. Not Enough Water

Boy, gardening can be contradictory, can’t it? Especially when it comes to figuring out if your plants need more water or less!

It seems that all the signs of overwatering are the same telltale signs of underwatering.

Blossom End Rot (BER) is no exception to this rule, either!

- When plants don't get enough water, there is nothing to dissolve and move calcium through the plant.

- There is just no way for the plant to take calcium up from the soil.

Plants need to transpire (basically meaning water loss or evaporation through upper plant parts and leaves and then taking up more water as needed). When they transpire, they continually draw up moisture which has calcium and nutrients in it.

That is how calcium gets through the plant to the different parts.

Plants transpire less if they are overwatered and don’t need to take up more groundwater.

They also cannot transpire if there is no water to lose.

- At the end of the day, watering issues – especially inconsistent watering issues – are the top cause of blossom end rot.

3. Overfertilizing

Fast, aggressive plant growth favors blossom end rot.

The short explanation for this is that when plants are in a slower-growing phase, calcium moves more slowly and is deposited better in different developing parts of the plant.

- In particular, an overabundance of nitrogen contributes to the presence of blossom end rot.

- This is because nitrogen promotes large, fast growth of stems and leaves.

- That type of growth results in poorly distributed calcium throughout the plants.

- It is the fruits that suffer from poor calcium distribution.

- Leaves and stems transpire more than fruits and vegetables.

- Leaves and stems lose more water, so they draw more water, and more calcium is left behind in the foliage.

So, if you promote high stem and foliage growth, you are setting up a situation where there is more of a draw away from the fruits, and the fruit gets less calcium.

The fruit of the plant, and specifically the blossom end of the fruit, are the last to get the calcium that is moved, and that results in BER.

- Balanced soil without too much nitrogen is one way to prevent BER.

- Resist overfertilizing and resist the urge to provide more nitrogen than what is needed for your plants.

Other possible causes of Blossom End Rot:

We’ve outlined the most common causes of BER because for most of us, treating these will stop blossom end rot. However, there are other causes and contributing factors that block calcium absorption.

These include:

- Low soil pH that inhibits calcium uptake

- Shallow watering that promotes shallow root growth and doesn’t help soil calcium from deeper in the ground move up the plant

- Root rot nematodes and root diseases that damage roots and stop them from being able to function properly

- Damage to roots caused by deep weeding and cultivation (this means you, the gardener! Be careful not to damage roots!)

- Understand that once in the plant and once it’s deposited, calcium cannot be redistributed in the plant, so increasing calcium uptake is the only way to get more calcium to the fruit and blossom ends

- This is done by correcting what is causing calcium uptake to be low or inconsistent

Better Tips for Preventing Blossom End Rot in Garden Vegetables:

- Soil test to see if calcium is really a problem

Odds are that it’s not. It’s one of the other factors mentioned above (usually a watering issue).

- Mulch

- Water deeply

- Water consistently (as in, on a regular schedule and at a regular, steady amount – one or two good, deep waterings per week, but no more)

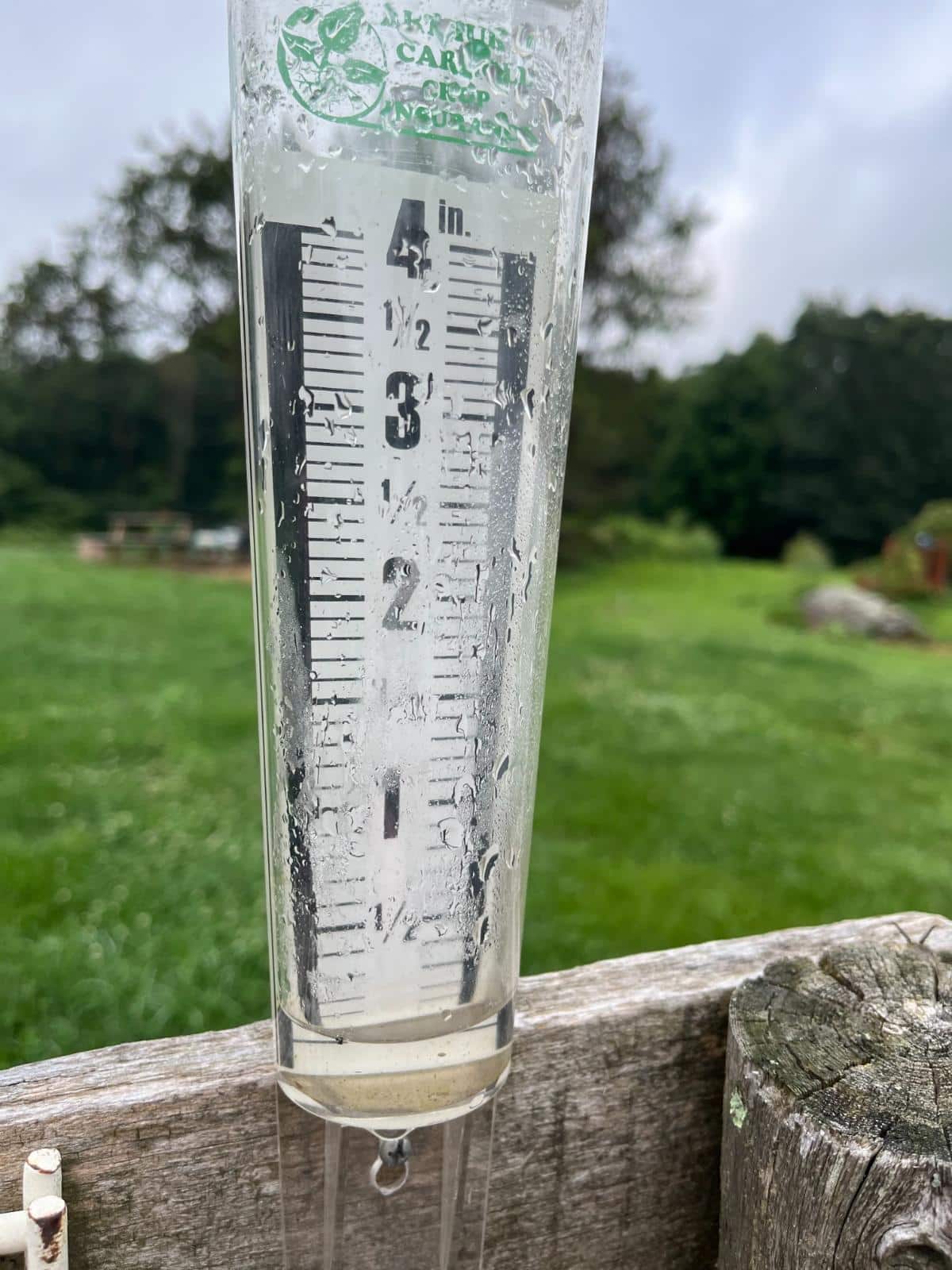

- Don't water if your plants are getting enough from rainfall

- Reduce fertilizer use

- Use supplements and additions like ground eggshells (which should be very finely ground) and antacids only when there is really a calcium SOIL deficit

What You Can Do to Immediately Correct Blossom End Rot in the Short Term

A lot of the causes of blossom end rot are things that we are or are not doing. That’s good because it means we can stop doing those things and stop blossom end rot.

More accurately, we can stop blocking calcium uptake so the plants get what they need!

Fortunately, if the plants are still producing, there is a solid chance that with good corrections, we can still get a useful harvest.

The first steps to take are to adjust watering:

- If plants are getting too much or enough natural water, do not provide any more (don’t water)

- Water infrequently, once a week, and deeply so roots go down and get better access to calcium in the soil

- Do not overwater

- If the plants are not mulched, mulch the soil to preserve and moderate soil moisture

- Use a rain gauge or a can sink into the ground to figure out if your plants are getting the right amount of water

Then, take steps that provide calcium and help the plant use the calcium it has:

- For an immediate calcium quick fix, spray plants with a solution of calcium chloride

- Remove any fruit or vegetables that show blossom end rot

- The damage is done to these fruits already, and they won’t improve, but getting them off the plant lets the plant free up calcium for other fruits coming behind it

- Removing damaged fruit also reduces the potential for disease and rot

- The earliest fruit is more likely to suffer from BER, so picking off bad produce can help the later-forming fruits, and this will often correct itself, especially if watered properly

- If there is enough useful flesh, you can cut away dark and rotted areas and safely use the produce

This will help you get a handle on blossom end rot in the short term and will save your harvest if the plants are still setting blossoms and fruiting. In the long term, consider a soil test and plan to use preventive measures like mulching and good moisture management.

The good news is that blossom end rot is not a disease caused by fungus, viruses, or bacteria. You don’t need to treat it with sprays or chemicals because that won’t stop it, and it won’t spread to other plants. It’s just an issue of calcium supply and demand, so if you can manage that, you’ll be in good shape.

Leave a Reply