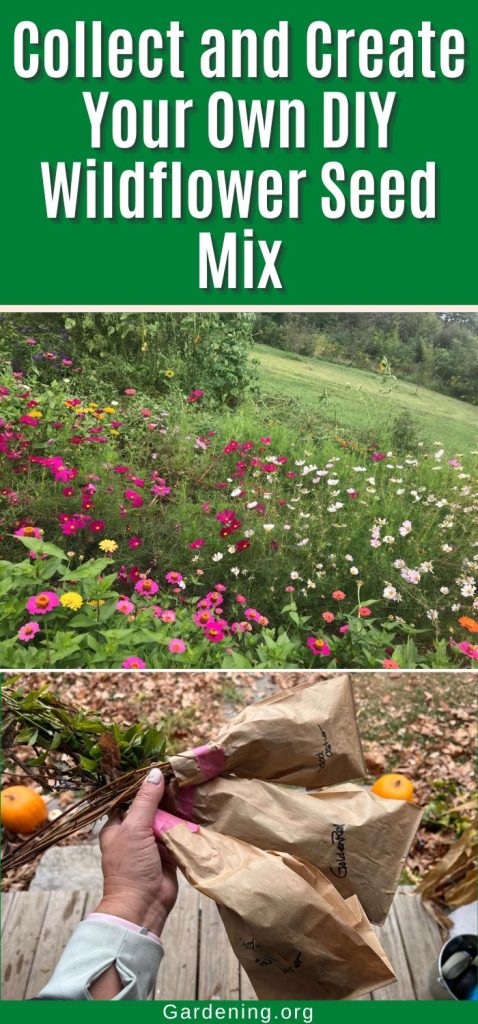

Who doesn't love a good wildflower patch?

They’re beautiful to look at, wonderful for pollinators and birds, and a lovely place to sit, watch, and enjoy nature in your own yard.

What we don’t love so much is the cost of wildflower seeds. This can be expensive if you are planting a patch of any appreciable size.

But you can easily collect and create your own local, native wildflower seed mix. And save a lot of money, too!

Jump to:

Why Collecting and Creating Your Own Wildflower Mix is a Great Idea

There are a lot of advantages to collecting and creating your own wildflower seed mix. We’ve mentioned the cost savings, but here are more reasons to make your own:

- Collecting from flowers that are already growing in your area means you know they will survive and thrive where you live

- You know the seeds are capable of naturalizing and reseeding themselves, coming back year after year

- Reseeding flowers create a low to no-maintenance garden patch

- Local plants are better for the local insects, birds, and wildlife that live where you do

- You can select native species to help support native plants

- You can select neutral, no-impact naturalized plants that won’t harm your local ecology like invasive species will

- You get to watch, track, and select local plants to suit your goals like target bloom time, continual blooming, spring, summer, or fall blooming, wildlife favorites, and more

- You are in control of the shapes and colors of flowers you save and plant

Choosing the Plants and Seeds

You’ll need to decide what you like and what you want to plant.

Other than that, selection is fairly simple. You just have to pay attention to your local surroundings and find plants that suit you.

You get to decide what suits you and your wildflower garden’s needs. There’s no “right” goal or answer.

Here are some tips, characteristics, and traits you might want to look for:

- Plants that flower at specific times of the year

- Collect plants spring through fall for a continuous garden

- Or, plan your garden according to the season in which you want your patch to bloom: Do you want just a late-blooming fall flower patch for late pollinators? An early spring patch to feed pollinators early on? A summer patch full of summer color for you to enjoy? A patch that is a mix so you have three seasons (or longer) to enjoy the blooms and beauty?

- Select plants according to color

- Foliage

- Structure

- Height

- Soil tolerance like flowers that grow in dry soil or flowers that do well in a boggy, moist patch

- Drought tolerant plants

- Frost or cold hardy plants

- Plants that are attractive at different life stages -- for example, as greenery or foliage, in bloom, with seed heads, in fall color…

- Plants that attract your favorite wildlife species, birds, or beneficial insects, butterflies, and bees

- Plants that are resistant to unwanted insects and creatures

- Plants with good disease tolerance

- Plants that readily reseed

- Plants that hold seedheads through the winter to continue to feed birds and wildlife

As you can see, there are many criteria and characteristics that you can select for. You can select for many at once, too.

The goal and design of your garden is your own. The best way to decide what you like and what you want is to get familiar with your local flora and fauna.

Focus on Native Plants

It is best to focus on native plants. That way, you are planting a patch that supports the local ecology, instead of creating more problems for it.

Double-check to avoid spreading invasive plants

Definitely stay away from any invasive species of plant or flower. You do not want to be part of the problem. Plant native species and be part of the solution instead!

Do what you can to support beneficial wildlife and insects and give them back the habitat they have lost to invasives.

This means that you need to pay special attention when you are identifying plants. Check more than one resource. See what is invasive. Be confident that what you are collecting is not harmful.

Not all flowers are native or invasive

Not all plants are native, but as long as they’re not invasive, they’re still fine. Many of us have flowers that have naturalized in our area.

Naturalized or naturalization simply means they’ve become, essentially, a translated or introduced plant that has become next door to a native, but without causing the damage and ecological harm that invasive species do.

So, naturalized non-native flowers are still harmless and beneficial to collect and grow, too.

Identifying Good Plants and Seeds to Collect

For collecting seeds for a wildflower mix, you can do away with a lot of the typical gardening “rules.”

You are in control. Your mix can include whatever you want it to include.

Collect what you like

To start off your collection, pick the flowers that you like.

When you go for a walk or a hike in the woods, what wildflowers do you see that attract your attention? What colors and shapes interest you? What do you think are just plain pretty? What do you notice the birds, bees, and butterflies flocking toward? What do you see that could fill a void in a certain time of year or season?

Your DIY wildflower collection should be one that brings you joy. It’s as simple as that.

Don’t worry if they’re “weeds”

The definition of a weed is a plant that is out of place. All garden plants are wild somewhere. What we’ve decided are valuable, or weeds, is really quite arbitrary.

Many wildflowers, even those used in mixes, are not something we would typically let live in, say, a vegetable garden.

Many flowers that were once considered troublesome or as weeds are not considered good plants and valuable flowers.

Take goldenrod and dandelions for example. Goldenrod is a prolific fall flower that serves great purpose. It is an important late season food source for honeybees and migrating pollinators.

Goldenrod has gotten a bad reputation because many people think they are allergic to it. The truth is, though, that most people are not allergic to goldenrod, and it is ragweed (which can look somewhat similar and blooms at the same time) that is the real problem.

And so, now, we like goldenrod. If Goldenrod grows where you live, it would definitely be a wildflower worth considering for its seed. And you should be able to find and collect plenty of it even into late fall.

Dandelions are one of the most prolific “spring” weeds. However, they are gaining in popularity as an important pollinator plant and an edible food source.

So you see, just because a flower isn’t something we might typically grow in a garden or that might at some point have been considered a weed doesn’t mean it should be left out of your mix. Things like early dandelions and late goldenrods are both good ways to get a longer-lasting bloom from your wildflower patch.

Do learn about aggressiveness and spread, though

That said, do read up a little on how aggressive some of these weeds can be. Put some thought into it and decide if you see that as a potential problem in your yard or garden.

For example, if your wildflower patch will spread dandelions all over your vegetable beds, are you willing to deal with that? Or will you curse yourself for creating a bigger weed problem there?

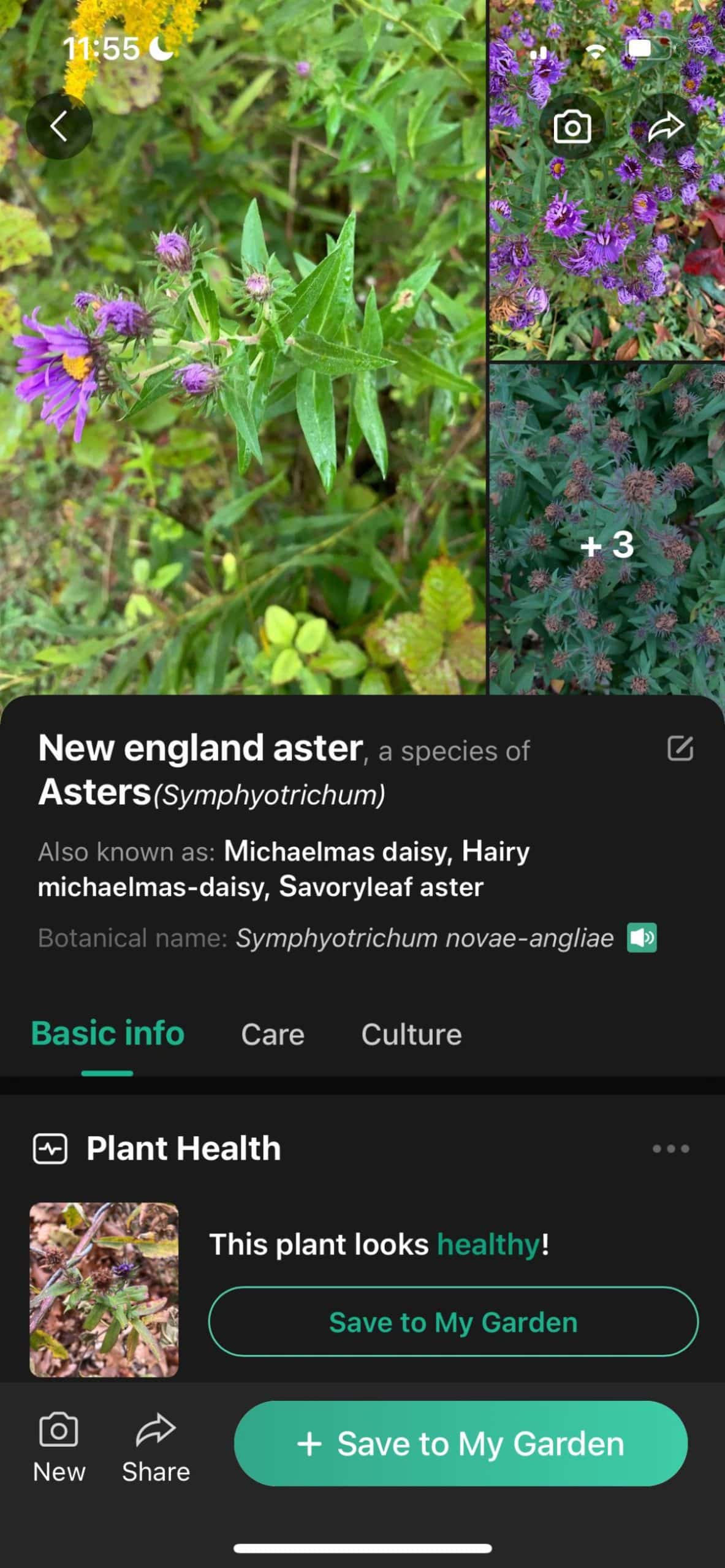

Use plant identification apps and other resources

You definitely want to know what you’re collecting and what you’re bringing into your yard. You definitely do not want to be spreading problem plants or invasives. Some plants may have other characteristics that are okay in the wild, but not personally acceptable for you in your garden bed.

The only way to know what could be a potential problem (or benefit) is to identify the plants you’re collecting seed from and read up on them.

Here are some suggestions for identifying and learning about wildflowers around you:

- Get a good plant identification app. There are good, free options. The free version (or paid) of Picture This is a good one to start with

- Use Google Lens or similar services to search for plant identifications and information. This is a good way to double-check the results of your plant app (because they are not always perfect) and/or identify plants at various life, growth, and seed stages.

- Back up your findings with an online search.

- Or, look up the plant in a local field guide or wildflower book. The more local the guide, the more likely it is to be accurate. But do keep in mind that plants and invasive species spread. The more recent the field guide, the better.

Track

It’s best if you start your search for wildflower seed potentials early in the year. This way, you can note the plants, identify them at different stages, and track their characteristics, including bloom time and attractiveness.

It’s fine to collect seed in the fall to get started, but you’ll have a nicer and more rounded mix if you begin searching, noting, and tracking plants throughout the next year. You can always collect and add these to your patch in the future, too.

Tag

When you find plants you love, tag them so you’ll know which were your favorites later on.

You can’t collect seeds until quite a while after the plant has blossomed. By then, it may look entirely different, and it might be hard to know which plant you wanted.

Here are some ideas to find the plant and location later on:

- Tie a piece of string to individual plants to identify them

- Tag several plants, preferably in different locations, in case something happens to your plant or its tag (like someone picks it or a roadside mower mows it down)

- Drop a pin in a Google Map (or your favorite mapping app) to identify the location of plants and tags. This will help you to return to them later in the year.

How to Collect Seeds for Your DIY Wildflower Mix

Once you know what you want, you just have to collect the seeds. That part is pretty simple.

Wait until the seeds are mature

First, you'll need to wait for the seeds to mature. If you collect wildflower seeds too early, they won’t be viable.

- Allow the flowers to go completely through their bloom cycle

- Leave flowers and heads on the plant so they can form and mature their seed

- Mature seed heads that are ready for collecting will typically have no petals left

- Seed heads will be dry and usually hard

- Some may become fluffy (like milkweed and dandelions), which helps them to blow and spread on the wind

- Others will be hard heads of dark seed (like coneflowers and Black Eyed Susans)

- You can pick the seed heads a little less than completely dry if you need to beat the birds to them

- It’s important to get to the seed heads before they completely shatter or drop

- Cut or break off the entire seed head with the stem on

- Put it in a paper bag, head down, and label the bag

Dry the seeds

- Make sure the seeds are completely dry before mixing and using

- You can usually tell if seed heads are dry from their hardness

- A good way to make sure the seeds are dried down without losing them is to keep them in a paper bag (which allows for enough airflow) and tape the bag around the stems

- Then, hang the stalks and stems as a bundle, bag down

- Hang them in a space with low humidity and moderately warm air, preferably with good airflow

- Let the seeds sit and cure for two to three weeks, then check them for dryness

- The bag will catch any seed that shatters or falls from the head as the seeds dry

- Some heads of seeds will not drop on their own; roll the heads between your hands or pick the seeds off into a container

Make your mix

Once the seeds are dry, you can make your mix.

- If there is a lot of excess plant debris (like leaf pieces, petals, etc.), you can winnow it off by spreading the seed on a tray and blowing it off or running a weak, low fan across the tray (a hair dryer on a cool and low setting works, too)

- For your DIY mix, some debris will not be a problem; you may or may not find it worth your time to winnow since the seed is for planting and not eating

- If the seeds are very light or very small, you may lose more by winnowing, and you should skip that step

- Now, mix the seeds you’ve collected into one large batch

- Try to keep an even ratio of different types of seed so that you don’t have one seed that overpowers the others (unless you want the mix to be heavy in one type of seed -- then you can adjust your percentages accordingly)

- If you do not plan to plant your mix right away, seal and store the bag until you are ready to use it.

- Store in a cool, dry place out of sunlight and away from warm heaters and appliances

- Desiccant packs like silica gel can help remove any excess moisture

How much seed do you need?

One-quarter of a pound of seed in the average commercial wildflower seed mix will cover between 250 and 500 square feet of soil. Use this as a general guide for your own mix.

Because your homemade mix won’t be as clean as a commercial mix, and you are likely to have more plant pieces that are not actually seed mixed in, go with a measurement closer to the high end of coverage.

In other words, use a rate of ¼ pound of homemade wildflower seed mix for 400 to 500 square feet of coverage.

This would be about a space 20 x 25 feet in area; multiply length times width to find your square footage.

Of course, you can adjust up or down and create as large or as small of a patch as you want. An area that is 20 by 25 feet is quite a large space!

Planting and Starting Your Wildflower Patch

You will plant your DIY wildflower mix the same as you would plant a patch started with a commercial seed mix.

There is a complete step-by-step guide to planting a wildflower meadow or patch here:

When to plant your custom-made wildflower mix

You can plant your wildflower seed mix in the spring, summer, or fall. Of these, Spring or fall are the two best choices.

It is quite likely that native plants and wildflowers may rely on a natural period of cold stratification in order to germinate, sprout, and grow flowers.

Stratification is a cold treatment. It happens in nature when seeds sit through a cold winter and are exposed to long periods of low temperatures.

Stratification is, in part, a natural defense against sprouting too early and being killed off by winter weather.

How does this apply to you and your DIY wildflower mix?

The seeds you collected will need to follow that same natural exposure if they are the types of seeds that require cold stratification. You can look this up online for many of the seed types you’ve collected, but it’s pretty safe to say that the seeds that naturally grow after winter have some level of stratification and cold exposure built into their growth cycle. Assume that they do if you do not know or can’t find out.

By planting in the fall, your seeds will get natural exposure because they will experience the same winter weather they would in the wild where you live.

If you’re not ready to plant in the fall, you can stratify the seeds over the winter and then plant them in the spring or summer. One good way to do this is to simply store the wildflower mix in your freezer or refrigerator.

For more on how to cold stratify your wildflower seed mix, read here:

Leave a Reply