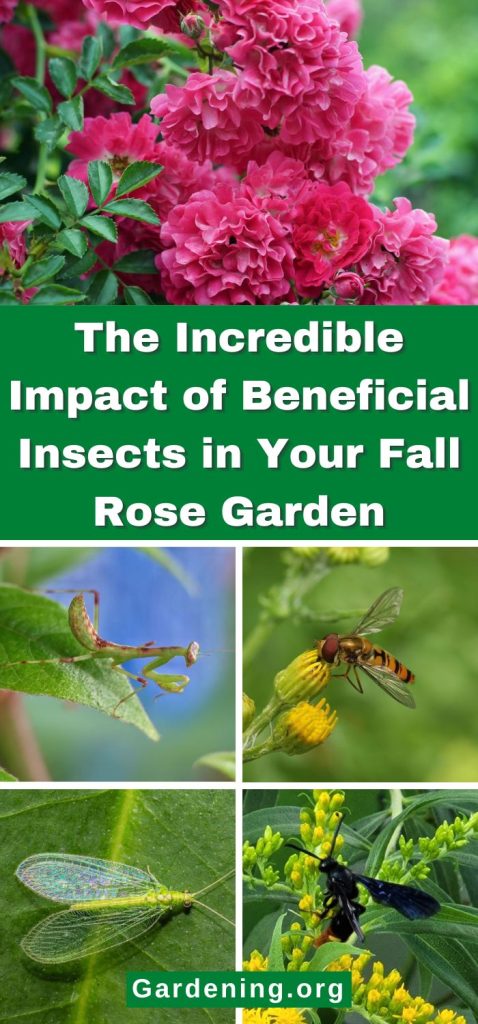

What are beneficial insects? These are helpful insects for the rose garden because they dine on insect pests that are eating your roses.

Bugs are labeled as pests when they eat your rose leaves and flowers. Fortunately, of the nearly 1 million known insect species, only about 1 to 3% of these species are considered destructive. The rest of the insect world pretty much mind their own business.

However, many beneficial insects eat destructive insects for lunch. Some of them parasitize pests. And many beneficials pollinate our food plants.

If you’d like to see a lot of beneficial insects in your rose garden, you can buy eggs of various insects – ladybugs, lacewings, and praying mantises are popular – and turn them loose among your roses in spring.

Here are some of the most popular beneficial insects that you might see in your rose garden.

Jump to:

Ladybugs

Y’all love ladybugs. Maybe not so much the Asian ladybugs, which are larger than the regular ladybugs and invade old houses in the fall. But both are great to have in the rose garden.

Ladybugs, both the adult beetles and the larvae, are voracious eaters, chomping through aphids and other small insects. They’re a joy to have in the garden. Also, they’re pretty cute.

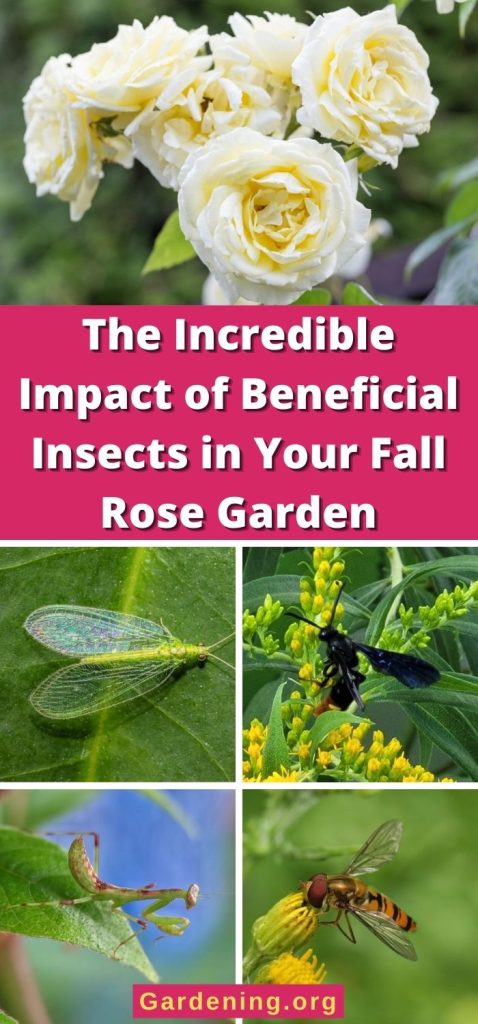

Lacewings

These look like a pale green skinny lady in an enormous iridescent ballgown. The lacewings are in the dragonfly family. The adults are mostly vegan, feeding mainly on pollen and nectar, though a few eat small bugs.

Their nymphs, however, look like tiny alligators, and they are out to eat anything they encounter – aphids, lace bugs, caterpillar beetle larvae, insect eggs, mites, and sometimes each other.

Lacewing nymphs resemble ladybug larvae, except they have a vicious pair of hooked jaws on the front of their head. They use these to grab fleeing prey, inject venom to paralyze the small insects, and suck out the juices.

A band of ants will guard a herd of aphids on your roses, and the ants will attack anything that threatens the aphids. They’ll even grab lacewing larvae in their jaws and throw them off the plant.

Some lacewing larvae have figured out a trick to get past the ants.

They’ll cover themselves in debris – lichen, dead aphids, and parts from the insects they’ve eaten – like a barbarian warrior. The larva is then able to sneak past the ants, who are apparently thinking, “Here is a walking pile of dead aphids. This seems legit.” Then the debris-covered larva can sit among the aphids, happily munching away.

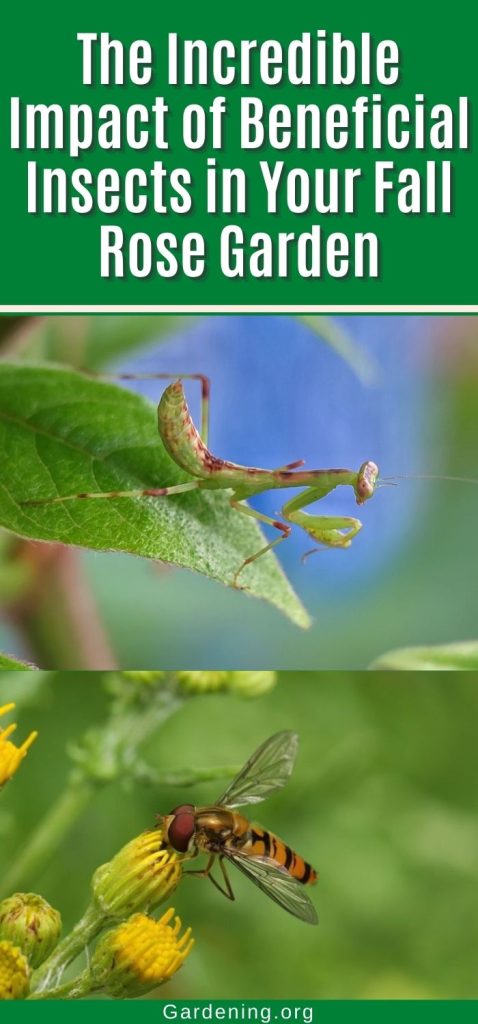

Praying mantis

Praying mantises are like tiny lions, devouring anything that crosses their paths. They’ll often be sitting on a rose bush with the remains of some insect clutched in its arms, chomping away.

Praying mantises are charming insects with their triangular, big-eyed head and characteristic front legs that give them their name. They are generally green or brown for camouflage.

They’re also fun to play with. If you put a mantis on your computer screen and start moving the cursor around on the screen, sometimes the mantis will chase it and try to catch it.

Mantis egg cases, which are a form of solidified foam, appear in the fall, looking like a brown packing peanut stuck to a rose cane. Leave these alone when you’re cutting back your roses. The young mantids come out of these in spring and sometimes devour each other because they’re so hungry for prey, and they’ll go to work on your spring rose garden, eating up aphids and other nasty insects.

Spiders (technically not insects but arachnids)

These guys get such a bad rap in general. Yes, caution needs to be taken with venomous spiders. But don’t take the sins of a few species out on the rest of the spider-verse. With the sheer number of mosquitoes and other biting insects that spiders trap, you could truthfully say that the majority of spiders work hard to keep you from getting bitten by other insects. Some spiders even prey on venomous species.

Spiders have created an incredible number of ways to trap unwary insects. Orb spiders create architectural wonders. Some construct neat little trap doors that they pop out of like a jack-in-the-box to grab their prey. Some just hang out in rolled-up rose leaves and stuff themselves with spider mites.

Woodlouse spiders look wicked evil, with a gigantic pair of hooked jaws, but they use these to grab pillbugs/rolypolys/sowbugs and eat them. Some, like the crab spider in the picture, will hide under a leaf or inside a flower and pounce on insects.

As much as possible, I allow spiders free rein in the rose garden. Obviously, if an orb spider built a giant web in the gazebo, I’d move her to a less public location. I let the less public webs remain in the yew bushes. Spiders are a net gain to the rose garden.

Assassin bugs

Assassin bugs range from a half-inch to an inch long, and they have a huge straw-like mouth part, called a proboscis, that they feed through.

Assassin bugs get their name from the way they ambush their prey and jab them with their proboscis. They inject salivary enzymes into the bug to break down their innards for easy sipping.

The assassin bug in the picture above lives on my damask rose bush, along with his kin. When Japanese beetles were swarming my rose, I’d occasionally see an assassin bug carrying a Japanese beetle around on its proboscis like it was a Slurpee from the 7-11.

Assassin bugs will catch beneficial insects as well as destructive insects, but they’re very good at taking out caterpillars, beetles, sawflies, and aphids. When you’re a predatory insect, everything you see looks like lunch.

Don’t try to pick up an assassin bug, though, because they’ll stab you with their proboscis. It hurts!

Wasps

Paper wasps, mud daubers, as well as smaller wasps are beneficial insects. In the rose garden, they catch caterpillars, beetle larvae, and other soft-bodied pests, chew them up, and feed them to their larvae grubs.

These wasps, along with solitary wasps, are friendly and don’t sting much unless they are defending their nests.

I made friends with the big cicada killers that hung around the Krug Park rose garden. These black-and-yellow striped hunters were over an inch long and looked mean! But they’d just sit on a little perch, like on a rose or a sprig of yew, and they’d fly out and chase away passing flies or spiders. Or they’d pounce on bits of mulch on the sidewalk.

But their main interest was catching cicadas. Cicada killers will catch a cicada or locust in the air, sting it into a stupor, then drag it into their underground nest as food for their larvae.

I like wasps overall and leave them alone. However, hornets and yellow jackets are straight-up means and all attitude, so I do my best to avoid them.

Hoverflies

If you see a small bee hovering near your rose blossoms, look more closely. Chances are that it’s not a bee at all but a hoverfly.

Hoverflies, also known as flower flies or syrphid flies, are an example of mimicry in action. That’s when a creature that’s usually prey keeps itself safe by mimicking something. Some insects disguise themselves as leaves or bits of bark. Others mimic creatures that sting or bite, so predators keep their distance.

A quick way to tell a hoverfly from a bee, wasp, or hornet? Look at the eyes. Hoverflies and other flies have big eyes that resemble that of a housefly, while bee eyes are small. Flies also have one set of wings, while bees have two sets. Wasps and bees have a tiny waist between the abdomen and thorax, but flies don’t.

Hoverflies are pollinators, though, just like bees. However, hoverfly larvae eat aphids and soft-bodied insects.

They also like sweat because it has salt, which is an essential part of their diet. That’s why they follow you around. Hoverflies don’t sting or bite, but they definitely tickle.

How to Attract Beneficial Insects to the Rose Garden

Plant flowers. The best way to bring in beneficial insects is by planting nectar-rich flowers around your rose garden.

There’s a lot to be said for adding other flowers to a rose garden. Plants do better in a community, and the additional flowers add beauty to the rose garden when roses aren't blooming.

Goldenrod is a popular favorite of many insects, and the flowers are tough and hardy since they’re native plants. There are also a number of improved goldenrod varieties on the market if you’re looking for some real eye candy. Goldenrods look stunning when their bright yellow is set behind a red or orange rose.

‘Autumn Joy’ sedum is also a favorite of beneficial insects. This reliable old favorite is still easy to care for and a gorgeous addition to the rose garden, especially in the fall.

Russian sage (Perovskia) is another low-maintenance favorite that covers itself with soft pastel purple blossoms, and beneficial insects love it.

Asters are beautiful fall flowers in deep purples and brilliant pinks but can be invasive in some areas. If it is, plant pansies instead – these will last from spring through the fall frosts and freezes and sometimes keep blooming through the first snowfall.

Give beneficial insects shelter. Give them some ground cover to hide out in, as well as dead leaves or areas with a little brush. Leave some fall leaves on the ground to let beneficial insects overwinter. Autumn leaves also act as mulch, insulating the ground against the cold.

Dial back on chemical use. When you use chemical controls, target them as tightly as possible on the pests. For example, spray only the area that actually has the pest insects on it. Bring in other control measures to knock out the pests. When you use a variety of control measures, you’re likely to succeed in ending the infestation more quickly than when you rely on only one.

The Best Way to Attract Beneficial Insects: Organic Rose Gardening

If you want to create a population of beneficial insects in your rose garden, you must stop indiscriminately spraying the roses with chemical insecticides. Full stop.

Concentrating on organic ways to take care of your roses isn’t easy ... at first. This work can be frustrating when you first stop spraying chemicals. Insect pests will appear. You patiently wait for the beneficial insects to show up, but they don’t appear! What’s the holdup, guys?

It’s true: There will be a void of insects in general at first (except the destructive insects) because building up an insect population takes time. It will take time for insecticide to get fully washed away by the rain and disperse enough to allow other insects to come in. And it also takes time for an insect population to reproduce enough or to fly in from elsewhere.

Learning new techniques, especially when it comes to organic gardening, also takes time. Don’t be hard on yourself if you do something wrong or if the results aren’t immediately what you want.

It’s okay to spray an organic insecticide – but only if there’s a large pest infestation that you haven’t been able to knock down by other means – and only if you limit the spray to the infestation.

Once you get beneficial insects in your rose garden, your job actually becomes a little easier. You’re not spending money on insecticides, and you’re not spending all that time every week spraying it. That means more time enjoying your rose garden. Consider that a total win.

Leave a Reply