Japanese knotweed is a wildly invasive weed that can take over your garden or lawn if left unchecked. Known for its rapid growth and resilient root system, knotweed has a tendency to drown out other plants and has even been known to damage concrete and other masonry!

Originally from Asia, Japanese knotweed was first introduced to North America in the 19th century. Once coveted for its ornamental appeal, Japanese knotweed was also used to create privacy hedges, but today it’s known to be a gardener’s worst enemy and can be very difficult to control.

But there is good news. While once the only solution to a Japanese knotweed invasion might have been synthetic pesticides, there are plenty of ways to eradicate this pernicious plant without needing to resort to harmful chemicals.

In this article we’ll cover all things knotweed -- from how to identify it, to common lookalikes and the top ways to remove Japanese knotweed from your garden. Every method we’ll cover for knotweed removal is safe for organic gardens, pollinator approved and perfect for keeping knotweed in check when practiced over time.

If you want to keep your garden free from knotweed, you’ve come to the right spot!

Jump to:

- The problem with Japanese knotweed

- Identifying Japanese knotweed

- Japanese knotweed lookalikes

- 7 ways to safely remove and control Japanese knotweed

- 1. Physical cane removal

- 2. Mowing

- 3. Goats

- 4. Barriers

- 5. Excavation

- 6. Horticultural vinegar

- 7. Solarization

- Creative uses for Japanese knotweed

- Food

- Crafts

- How to make your own solitary bee home using Japanese knotweed:

- Conclusion

The problem with Japanese knotweed

Japanese knotweed is an incredibly invasive plant and can be found on every continent except Antarctica. It’s rapid growth habit and resilient nature make it adept at tolerating a range of growing conditions and, once it starts growing in a location, invasions are usually sudden and explosive.

In nature, Japanese knotweed doesn’t have many natural predators as it is too tall and rigorous for many herbivores to bother with. As a result, knotweed growth is usually left unchecked and plants can readily overwhelm ecosystems, outcompeting slower growing native plants in no time. This means that knotweed can dramatically decrease biodiversity in affected areas.

Japanese knotweed is such an aggressive competitor with native plants due to its fast growth rate. Knotweed can grow quite large (over 8’ tall) and drown out shorter species. Beyond that, its fast growth means that it rapidly depletes soil of its minerals and nutrients making it difficult for other plants to survive in areas where knotweed is present. Reducing native plants changes biological landscapes, affects native animals and can even encourage erosion due to lack of plant life.

Beyond knotweed’s influence on native plants and animals, Japanese knotweed can be very destructive to buildings and other architecture in a short amount of time. Knotweed’s vigorous roots can take advantages of weaknesses in drainpipes, concrete and other masonry, weakening building foundations, fracturing pavement and causing other issues.

Both removal and the damage caused by knotweed can be quite costly for property owners. Canes can put pressure on fences and walls, while roots can grow over 20’ long and are able to warp concrete and block drainage systems.

Because knotweed tends to spread in areas where there’s lots of human activity, it is a common pest plant in many gardens and developed areas. In fact, disturbed landscapes, such as in new housing developments and along highways, are prime areas where knotweed can take hold. This is due to the expanses of bare topsoil and an abundance of sunlight that come with bulldozed landscapes and new building projects.

Once established, knotweed grows incredibly fast – up to 10’ in a single growing season. Even worse, plants are extremely difficult to eradicate as stems and roots frequently snap when pulled. To remove knotweed, often the entire root system needs to be dug up; however, even a small sliver of rhizome as large as a fingernail is enough for a new plant to sprout from, so removal can be very difficult.

Beyond rhizomes, knotweed can additionally spread through seeds which are readily airborne thanks to their winged, papery outer coatings.

Identifying Japanese knotweed

Japanese knotweed is most often spotted growing in clusters along highway margins, hiking trails, stream banks, edges of tree lines and fields. Preferring full sun, it can also grow in part shade and thrives in areas with moist, rich soil. Knotweed can adapt to dry conditions too; however, plants usually grow shorter and more stunted.

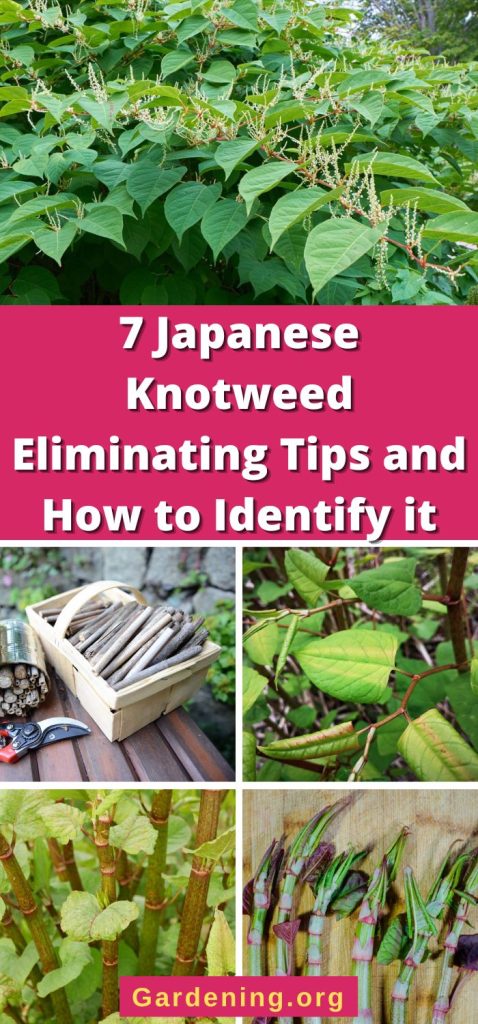

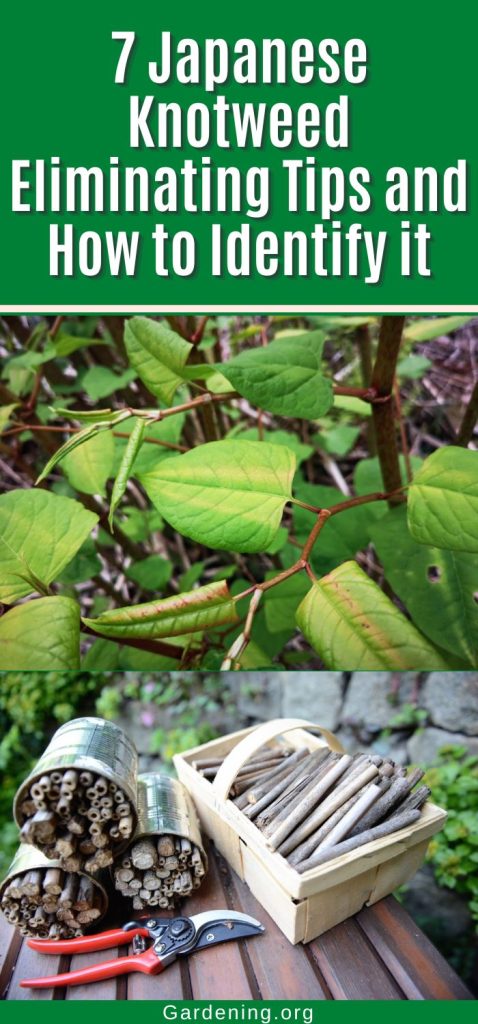

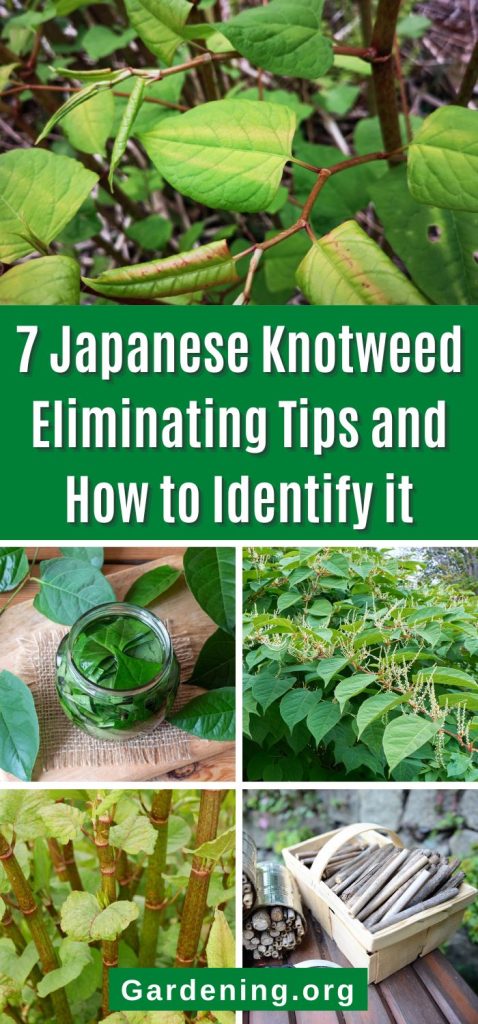

Rather bamboo-like in appearance, Japanese knotweed grows in long robust canes that regularly grow 5 to 8’ tall. Canes are divided by knobby nodes that often have a papery covering. The cane lengths between nodes are hollow and the canes themselves often have a reddish-brown, at times speckled, coloration to them. Under pressure, knotweed canes snap very easily, which can aid with identification.

Knotweed canes frequently have lots of branches and tough, spade-shaped leaves that narrow towards the tip. Leaves grow in a zig-zagged pattern and are green to reddish in coloring. Growing between 2 and 7” long, leaf widths are about two-thirds as long as their lengths. Leaves are smooth and without hairs and usually have white veining and darker reddish-brown petioles.

When mature, knotweed will bloom an abundance of foamy sprays of tiny off-white flowers, which first appear in July. Flower plumes are about 4” long, usually have a cascading form to them and don’t produce any noticeable fragrance. By August or September, flowers will develop into small, dark seeds with winged coverings that help with seed dispersal.

Knotweed also spreads via rhizomes that are dark brown in color. If you cut into a rhizome, interiors usually have an orange to yellow hue. These fast growing rhizomes can grow over 20’ horizontally by 10’ deep, helping to explain why knotweed is so difficult to eradicate and why it’s such a formidable foe in the garden.

At the end of the season, Japanese knotweed leaves will yellow and die back, but dead canes will remain visible throughout the winter season. Old canes are often straw-colored and are dry, hollow and woody. However, don’t let their appearance fool you; beneath the ground, knotweed rhizomes are very much alive, just dormant and waiting for spring to regrow.

In spring, Japanese knotweed canes begin to sprout in clusters of new shoots that resemble asparagus spears. Young shoots grow quickly and usually have a reddish-purple cast to them, which turns into a more muted green as shoots mature. Shoots can grow up to 4” a day during spring and have reddish-purple, curled leaves, which unfurl as the plants grow.

New shoots usually appear at the base of old knotweed canes and are most conspicuous due to their bright pink or red tips. Because of their height, new plants can be difficult to spot until growth accelerates towards mid- to late spring.

In general, Japanese knotweed is most easily identifiable in summer because it will be fully mature, tall and with lots of recognizable flowers and leaves. Of course, if you have a keen eye, you should be able to identify it at other times of the year too.

While Japanese knotweed is the most common variety you’re likely to find, other types of knotweed include Giant Knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis/Reynoutria sachalinensis) and dwarf knotweed (Fallopia japonica var. ‘Compacta’).

Japanese knotweed lookalikes

While Japanese knotweed has some key identifiable characteristics, it is often confused with a few other plants. Due to their segmented stems, leaf shapes and other factors, it is understandable why this misidentification can occur. However, reading up on common plants that resemble knotweed can help you finetune your identification skills so you can easily tell these plants apart.

Bamboo

The most likely plant to be confused with knotweed, bamboo and knotweed look quite a bit alike, thanks to their segmented, knobby stems and rapid growth habit. On closer inspection however, a few key differences appear. Notably, bamboo has larger leaves and knotweed’s stems will snap under pressure, while bamboo’s stems are sturdier.

Horsetail

Another plant commonly confused with knotweed, horsetail only resembles knotweed when it is very young, due to its segmented stems that appear in spring. As horsetail matures, it develops spindly, thin leaves in brushy masses that don’t resemble knotweed at all. Horsetail also remains much smaller than fast-growing knotweed.

Lilac

Common lilacs are usually grown as ornamental flowers in gardens and landscapes; however, their spade-shaped leaves bear some resemblance to those of knotweed. Unlike knotweed, lilac leaves grow opposite to each other, rather than in a zig-zag pattern, and lilac stems are sturdier and woody.

The most obvious difference, however, is evident when both plants are in flower. Lilac blossoms are larger and highly fragranced and are often purple in color, although they come in white too.

Dogwood

Like lilac, dogwood is another perennial shrub that is often mistaken for knotweed due to its leaf shape and color. Dogwood can also grow quite readily and produces creamy-toned flowers in spring that can add to the confusion with identification. Unlike knotweed, however, dogwood’s stems are sturdier and woodier, while knotweed stems can snap under pressure.

Broad-leaved dock

A common weed, dock is most commonly confused with knotweed when it’s still young because of its leaf shape. However, as dock matures, it won’t grow nearly as large as knotweed and maxes out around 3’ tall. Stems, while hollow, also have a white pith which is noticeably absent in knotweed stems.

Other common lookalikes include:

- Lesser knotweed (Persicaria campanulata)

- Giant knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis)

- Dwarf knotweed (Fallopia japonica var. compacta)

- Russian vine (Fallopia baldschuanica)

- Heart-leaved houttuynia (Houttuynia cordata)

- Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

- Bindweed (Calystegia sepium)

- Himalayan honeysuckle (Leycesteria formosa)

- Red bistorts (Persicaria amplexicaulis)

- Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)

7 ways to safely remove and control Japanese knotweed

Japanese knotweed is not like other weeds. This invasive plant is a tenacious grower and incredibly resilient, so eradicating it will take a bit of knowledge and persistence. But it is doable, even in the organic garden.

Of course, the quickest way to remove knotweed is by dosing it with glyphosate (the primary ingredient in Roundup). However, glyphosate has been linked to a number of health problems, including some cancers and infertility. Beyond that, glyphosate can cause harm to aquatic organisms, bees and other pollinators and other environmental concerns.

Luckily, there are all-natural, organic options for Japanese knotweed control. These remedies may take a bit more work and consistency to implement but, over time, they will eradicate knotweed from your property and will do so safely with no damaging consequences for you, pollinators or other at-risk species.

1. Physical cane removal

Cutting and destroying canes is one of the most effective ways to remove Japanese knotweed, but it’s a method that requires some time and perseverance. Because of knotweed’s vigorous root system, the goal is not to completely eradicate these weeds in one fell swoop, but rather to slowly weaken the plants over a length of time so they are not strong enough to return.

To begin, as soon as knotweed appears in spring, cut off all canes and sprouts as close to the ground as possible. A sharp pair of garden shears or loppers is usually all you need. Once done, take care to gather up all cut vegetation, as a small sliver of plant material is enough to generate more knotweed.

For the remainder of the growing season, from spring through August, continue cutting all sprouted knotweed stems down to the ground at two to three week intervals. Doing so will deprive the plants of the nutrients they need and will require them to expend energy on new growth. Over time, with persistence, knotweed patches will weaken, grow back slower and, eventually, die back entirely.

If you decide to go this route, be careful when disposing of all knotweed material to prevent if from regrowing. Never place knotweed directly in compost piles and be sure to contact your local transfer station prior to throwing knotweed away to make sure they accept invasive plants.

Alternatively, place all cut knotweed stems on a tarp or other plastic surface and allow the plants to dry out completely before disposal. This will ensure plants can’t regenerate. After drying, knotweed can be disposed of in your trash barrel or burned (knotweed is not very flammable when fresh). If you decide to dry out knotweed debris, just make sure no pieces get washed away by rain or blown by wind prior to disposal.

2. Mowing

As with physical removal, repeatedly mowing over a Japanese knotweed patch will weaken weeds so that, eventually, plants come back slower, smaller and then not at all.

Depending on where your knotweed patch is located, mowing may not be an option. However, if you can mow over your knotweed, this is a pretty effective and easy means of controlling this invasive weed.

To make sure knotweed remains a manageable size for your lawnmower, begin mowing over weeds early on in the season when canes are still small. Thereafter, mow every two to three weeks to ensure plants don’t get too long or unwieldy between mowings.

3. Goats

Another much more fun method of physical knotweed removal involves goats. It may sound wild, but in many areas you can actually hire goats to devour patches of invasive weeds, like knotweed and poison ivy. Known as “goatscaping,” this technique can be very useful for knotweed control, especially when combined with barrier methods of weed control.

Prior to hiring goats, you’ll need to ensure that your yard is “goat safe,” by removing anything that may harm your visiting goats, like rusted wire, glass or plastic scraps. You’ll also want to adjust your expectations. Goats may not remove every last stem of knotweed, but they can dramatically reduce any patches so that any remaining plants are much easier to tackle.

To hire goats, check your local listings and ask around to find some leads. Once you’ve made contact, goatscaping companies will give you an estimate for the service based on the size of your yard, the types of weeds to be removed and other factors. Keep in mind that some companies may choose to only service larger properties, so you may need to do a bit of research to find a service that’s right for your home.

Once you’ve hired your goats, expert handlers will arrive on site before the goats do to set up temporary electric fences to contain the goats. These handlers will remain onsite during the length of the project to keep an eye on the working goats and make sure everything runs smoothly.

An added perk of hiring goats is that they’ll provide you with an all-natural fertilizer while grazing. Win-win!

Beyond knotweed, goats can help to eradicate lots of other invasive plants too, such as:

- Kudzu

- Bittersweet

- Multiflora rose

- Sumac

- English ivy

- Japanese honeysuckle

- Poison oak

- Poison ivy

4. Barriers

Japanese knotweed is a hardy plant and has even been known to grow through concrete, so barriers are usually not enough to contain it on their own. That said, combining barriers with physical removal of canes or goatscaping is a wonderful way to tackle your Japanese knotweed problem. Over time, these methods can eliminate knotweed without needing to resort to any chemicals.

After cutting down knotweed canes to the ground, cover the affected area with layers of dark material and secure the material with landscape staples, bricks, stones or other heavy objects. Sheets of cardboard, plastic tarps and weed barrier fabric all great barrier options.

Once you’ve laid down your barrier, you’ll want to leave it in place for the entire growing season. As time passes, the knotweed stems beneath the barrier will shrivel away due to lack of light, water and nutrients. Throughout the season, you will want to keep an eye on the area though, making sure no stems poke through or rhizomes escape beyond the physical barrier.

To keep rhizomes from spreading, you can also bury the barrier material a few feet underground around the perimeter of the area you’re treating. This is the same method that is used to keep running bamboo in line in landscapes, but it works for knotweed too.

5. Excavation

If you have a small area of knotweed to tackle, digging up roots is an option as well, but it will take a bit of finesse. Knotweed rhizomes can grow over 20’ long and 10’ deep and a small section of rhizome left in the earth is often all it takes for knotweed to regrow.

That said, removing as much of the root system as you can will significantly weaken your knotweed patch and repeated diggings will usually ensure success. If you don’t want to excavate the area more than once, after digging, cover your soil with weed barrier fabric or another sturdy barrier option to prevent knotweed from regrowing.

If you have a larger area to tackle, you can also consider hiring professionals to dig up your knotweed patch. This is a more expensive option but will guarantee you remove all knotweed in your yard all at once.

As with cutting stems, when you’re removing knotweed rhizomes, take extra precautions as root systems readily snap and any broken section can regrow more knotweed. After removing the rhizomes, allow them to thoroughly dry out before throwing them in the trash or burning them to prevent future knotweed spread.

6. Horticultural vinegar

Horticultural vinegar is different from the standard vinegar you’ll find in your kitchen as it has a higher acidity content. Whereas regular distilled white vinegar has an acidity level of around 5 to 6%, horticultural vinegar is much more concentrated with an acidity content of 20 to 30% or higher.

Because of this high acidity level, proper care should be taken when using this product, including wearing safety glasses and protective gloves to prevent skin burns.

Horticultural vinegar can be sprayed on knotweed leaves and stems with a standard garden sprayer. Once the vinegar makes contact with plant tissue, it will dissolve the plant’s cell membranes, causing the plant to dry out in the sun.

As with physical removal of knotweed, you will likely need to apply horticultural vinegar several times throughout the growing season to fully destroy your knotweed patch. While upper leaves may be damaged by a single application, plants may resprout. Repeated applications, however, will weaken the plants down to the roots so that they eventually won’t have enough energy to regrow.

While foliar sprays will work over time, it you have a small patch of knotweed, you can also try injecting horticultural vinegar straight into the stems. This will kill the plant directly but, if you have a large knotweed patch, this method may be too time consuming.

7. Solarization

Solarization may seem a lot like barrier methods at first, but it adds another important element: heat. Solarization is an amazing, chemical-free way to rid your garden of all sorts of noxious pests -- from weeds like knotweed, to destructive, soil-dwelling critters like squash vine borers.

Solarization should be done during the summer, ideally during July or August as they’re the hottest months of the year. This technique uses the interplay of moisture and plastic to rapidly heat up soil and maintain a soil temperature of 110° F, which will slowly cook and kill any invasive weeds and other pests in the soil. Additionally, because sunlight is so important for this method, it works best in sunny areas and might not be ideal for knotweed patches located in shady spots.

To begin, you’ll first need to cut down your knotweed patch to the ground, or as close to the ground as you can. Next, deeply water the ground all around where your knotweed was growing, making sure water really penetrates the soil. For an extra, weed-killing boost, you can also lay a soaker hose over the area to keep the soil well moistened.

Next, spread a sheet of solid, clear plastic over your soil and beyond where the knotweed canes are to ensure you’re treating the underground rhizomes too. Then, fasten the sheet in place and wait.

You’ll want to leave the plastic sheeting in place for at least four weeks. During this time, try to resist the temptation to remove the plastic, because you want to keep soil temperatures high to cook the knotweed’s root system. While this process is taking place, be sure to keep an eye on your plastic sheeting, checking from time to time that the plastic remains in place and no canes or rhizomes appear beyond the area being treated.

After your soil has been solarized, remove the sheet and apply a thick layer of mulch.

Creative uses for Japanese knotweed

Because Japanese knotweed is such a ubiquitous plant, it makes sense to try to find uses for it when you can. Happily, there are quite a few ways you can repurpose knotweed once you’ve pulled it out of your yard. We’ll share a few ideas here, but feel free to get creative with your projects.

Keep in mind that care should always be taken when harvesting knotweed to prevent its spread. Whether removing it as a weed or gathering it for recipes and crafts, make sure that you collect all sections of cut knotweed and properly dispose of it. A foraging bag, or simple plastic bag, can ensure you don’t accidentally leave any knotweed segments behind.

Food

Surprisingly, knotweed is actually edible at certain parts of the year and is quite rich in many vitamins and nutrients, including vitamin C, manganese, zinc, potassium, phosphorus and the antioxidant resveratrol.

A relative of rhubarb, knotweed has a slightly sour taste, but also displays a certain savoriness that rhubarb is lacking. Pairing well with sweet fruits, like grapes and apples, knotweed can turn a bit mushy when cooked, but that quality can be used to its benefit when knotweed is cooked into dishes like pies, mousses and purees.

If you want to eat knotweed, you’ll want to take care where you harvest it and know your surroundings well. If you’re eating shoots straight from your backyard, you’re probably okay, but many knotweed patches along highways, trails and similar areas are often sprayed with pesticides. For this reason, only harvest knotweed that you know has not been sprayed and is safe to eat.

Knotweed is best harvested in early spring when shoots are young and tender and no taller than 1 to 2’ high. Once knotweed shoots grow over 2’ tall and are easily snapped, they are too old to eat. This is because, as knotweed ages, it becomes fibrous and bitter and is unpleasant to eat.

Once harvested, pick off leaves, cut away fibrous bases and peel the stems to remove their tough skin. All scraps should be properly disposed of to prevent knotweed spread.

Peeled stems can be cooked into dishes, pureed or pickled. Some fun ways to use knotweed in recipes include:

- Pies

- Pickles and lacto-fermented pickles

- Pureed and added to banana bread or other baked goods

- Sorbet

- Fruit leather

- Relish

- Salsa

As texture is the primary issue with cooked knotweed, you’ll want to seek out recipes where its soft consistency makes sense and won’t detract from the overall dish.

Crafts

Beyond cooking, Japanese knotweed can be used in many craft projects too. Allow yourself to get creative and see how many ways you can repurpose this meddlesome weed.

If you’re into paper-making, Japanese knotweed’s fibrous nature lends itself well to such projects.

The hollow canes of Japanese knotweed make it well suited to many purposes, such as flute making and creating pan flutes.

For a pollinator garden-friendly project, you can also make knotweed canes into a home for solitary bees.

How to make your own solitary bee home using Japanese knotweed:

While honeybees get a lot of hype (and with good reason), the majority of native bees are actually solitary species that don’t live in hives. Instead, many of these bees burrow in the ground or in piles of dry leaf litter and debris. To help these native pollinators out, you can make a simple bee hotel with knotweed canes.

Different sorts of solitary bees will be attracted to this set up, including mason bees, leafcutter bees and miner bees.

What you need:

- Knotweed canes

- Garden shears

- Twine or wire

The steps:

- To begin, you’ll want to cut knotweed canes into 6” sections using garden shears. One end of the cane should be open for bees to enter, and one end of the cane should be closed to protect slumbering bees. To achieve this, locate cuts around cane nodes, which are not hollow. You’ll need to cut about 12 lengths of knotweed canes to make your bee hotel.

- Once you’ve made your cuts, tie your knotweed canes together using a length of hemp or cotton cord or some wire. Wrap the canes together tightly around the middle, looping the twine around many times until you’ve got a securely wrapped bundle.

- Next, take approximately 12” of twine and make a loop around your bundle to form a hanger.

- Finally, hang your bee hotel and wait for the new residents to arrive. You’ll know bees have moved into your hotel when the ends of knotweed canes are capped off with a bit of mud or clay.

Where to locate your bee hotel:

Place your bee hotel outside in spring in a sheltered area. Generally speaking, placing it under a roof eave or beneath the sheltering branches of an evergreen tree is a good idea to help protect bees from harsh weather.

For security, locate your bee hotel about 6 to 7’ above the ground and try to orient it so that it is facing south or southeast. Arranging your bee hotel in this manner will maximize the amount of sun that hits your hotel, helping to gently warm the sleeping bees inside.

Conclusion

Japanese knotweed can be a menace in the garden. It is incredibly resilient, spreads rapidly, is difficult to eradicate and doesn’t really have any natural predators. But no matter how tough Japanese knotweed at first appears, there are all-natural ways to eradicate this pesky plant.

Once, gardeners may have picked up a bottle of synthetic herbicides to remove invasive plants, but we know better today. Chemical herbicides have long lasting and far-reaching consequences for human health, pollinators and the environment we live in. Today, with an increased understanding of plants and the interconnectedness of the natural world, there are organic alternatives to knotweed control.

From cutting stems to solarization to renting goats, gardeners have many tricks up their sleeves to attack Japanese knotweed patches. These methods, when practiced with consistency, are just as effective as chemical alternatives with none of the risks.

But beyond simply eradicating knotweed, part of the secret to its control is to find ways to put this weed to use. And from serving as a base to numerous recipes to providing a habitat for solitary bees with its dried canes, there are lots of ways to gain value out of what was once considered to be only a noxious weed.

References:

- Holmes, Kier. “These are the Safest Ways to Get Rid of Japanese Knotweed in the Garden.” Martha Stewart. 6 July 2022. 8 January 2020.

- “How to Solarize Invasive Plants.” Cornell Cooperative. 6 July 2022. 2022.

- “Itadori (Japanese) Knotweed Identification and Control.” King County. 6 July 2022. 15 February 2021.

- “Japanese Knotweed: Hunting, Harvesting, Cooking and Recipes.” Forager Chef. 6 July 2022.

- Kuchta, David. “How to Solarize Soil in 13 Easy Steps.” Treehugger. 6 July 2022. 26 July 2021.

- Martini, Paolo. “Japanese Knotweed Identification – A Complete Guide.” Knotweed Help. 6 July 2022. 28 June 2022.

- “Natural Control of Japanese Knotweed.” Pumpkin Brook Organic Gardening. 6 July 2022. 2022.

Leave a Reply