Encouraging the Living Soil Beneath Your Feet

Regenerative agriculture is a hot topic right now, and rightly so. Practices that look holistically at the soil and its functions within a watershed and an ecosystem are needed in our human-ravaged planet.

What can you–can we–do to help, in our own garden, within our own sphere of influence? How can we get on board? You can restore the soil to a healthy, resilient condition, reduce your need for fertilizers and pesticides, and see happier, healthier plants.

A keystone of regenerative agriculture is the restoration of what many call the topsoil. What do I mean, restoration? Isn’t there already soil there?

Jump to:

- How Soil is Formed

- Enter the Plow–Stage Left

- The Living Stuff in Soil–The Soil Food Web

- Microorganisms

- Soil Texture

- Soil Structure

- Soil organic matter

- Let’s Build the Soil!

- Cover crops and green manure

- Compost

- Mulch

- Compost Tea

- Park your rototiller

- Problems with rototilling

- Alternatives to tilling

- Continue Your Efforts

How Soil is Formed

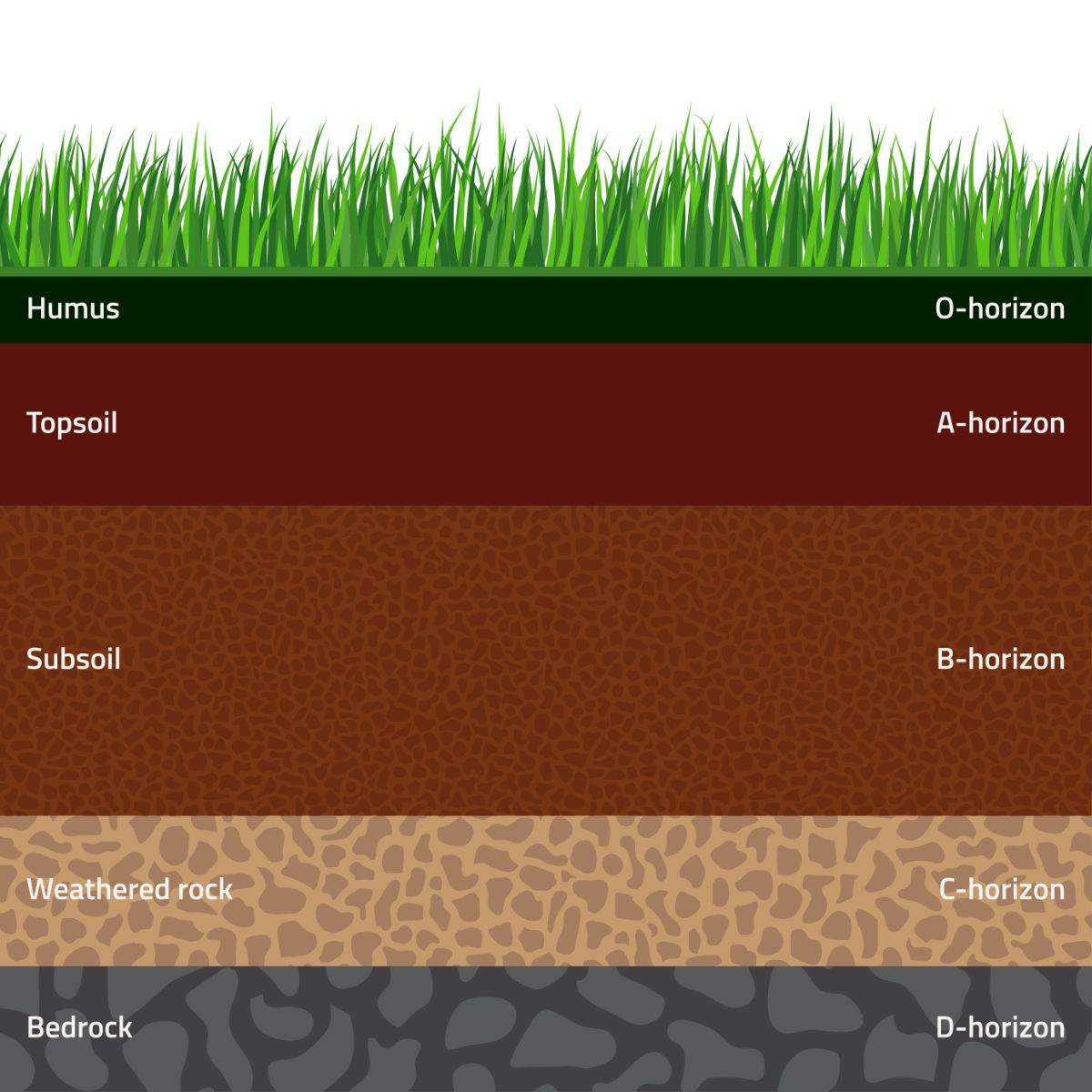

Soil formation is a process that usually, left to natural processes, takes thousands of years. Rock is weathered by the actions of wind, rain, erosion, freezing and thawing, biological and chemical activity into smaller and smaller pieces.

Bedrock fractures to become boulders. Boulders become rocks. Rocks erode and weather to gravel, and finally to smaller soil-sized particles that make up our sand, silt, and clay.

Living plants and animals die and fall to the earth, are rendered down to their molecular components by other animals, bacteria, and fungi. Some parts are “inedible” in that they resist breaking down farther and become humus.

Over time, these layers of weathered parent material, humus, actively decaying plant and animal matter, and soil microorganisms become what we know as soil. Living soil.

In a delicate aerobic and anaerobic balance, controlled by temperature, moisture, oxygen levels, and carbon inputs, these soils have been growing and evolving since before humans first swung a stone ax.

Enter the Plow–Stage Left

Somewhere in our history, our ancestors took up agriculture. They made tools to change the landscape, to make it more fitting for growing crops for food, for us and our newly domesticated livestock.

Plows turned the soil, inverting delicate balances of microbes and fungi that had evolved to live in that specific environment. Organisms that had never known the sun or been exposed to the air were flipped upside down to bake and die in the bright sunlight. Those that needed oxygen to live were buried.

The delicate balance of the living soil was lost. What took several millennia to build was changed and sometimes lost in a generation.

Today, most of our soils are a far cry from the rich, fertile, loose, and living layers that they were before humans came. Step into a modern farm field and look under the canopy of corn or soybeans; the ground is hard and sterile. Chemical synthetic fertilizer is needed at a rate of tons per acre to maintain yields. We try to do with chemicals what the soil used to do naturally.

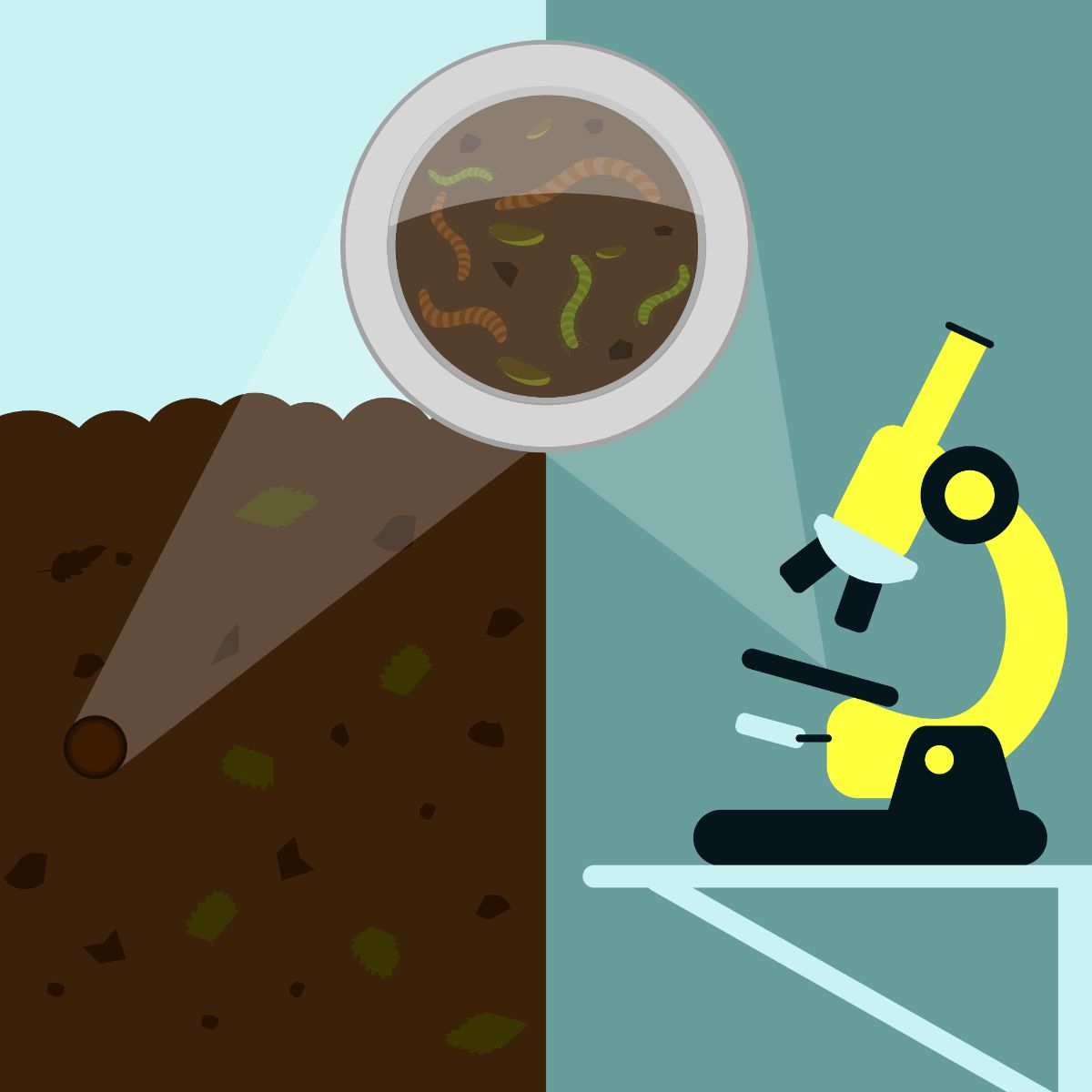

A look at the soil with a microscope to see the microbial activity level would be even more telling.

Chances are good, whether your garden is in an area that was previously an ag field, or a suburban backyard, that your soil was negatively impacted by the human patterns of industrial agriculture and urbanization.

While we cannot restore the soil overnight to its previous state of health and vigor, there is much we can do to get things going in the right direction over the course of just a few growing seasons or even a few weeks.

The results will be beneficial both to the soil and to your gardening.

The Living Stuff in Soil–The Soil Food Web

Soil can start to sound complicated. What we called dirt and played in as kids is actually alive and can be considered a whole ecosystem in itself.

Actinomycetes, bacteria, nematodes, fungi, mycorrhiza, symbiotic relationships, cation exchange, it all starts to sound pretty complex, and it is.

Don’t worry. A general idea of how it works is all that is needed. Let’s go through some standard terms and ideas. If you understand the “why,” the “how” becomes easier to accomplish successfully.

Microorganisms

When talking about soil and soil building, microorganisms are just tiny little helpers. In this case, mostly bacteria and fungi. In your kitchen or refrigerator drawer, those are bad things, but in the soil, they help to break down plant residues, and also help plants to absorb nutrients.

There can be as many as a billion bacteria and a million fungi in just a teaspoon of soil.

Actinomycetes are just bacteria with a different form and function, and are crucial in breaking down plant residues and making nutrients available to plants.

Fungi, we know when they are larger–think mushrooms. Fungi in the soil are smaller, often looking like threads. Miles of fungal hyphae exist–or should exist–in your garden.

Many of these tiny organisms have a symbiotic relationship with the plants in your garden.

For example, the roots of your tomatoes exude carbohydrates and proteins, which bacteria and fungi feed upon. The fungi and bacteria hold plant nutrients like nitrogen in their bodies, which is available for the roots to absorb when the organism dies. Without them, these nutrients would likely be leached away through the soil and out of reach.

Microorganisms are your army of helpers to keep your plants vigorous and healthy.

Soil Texture

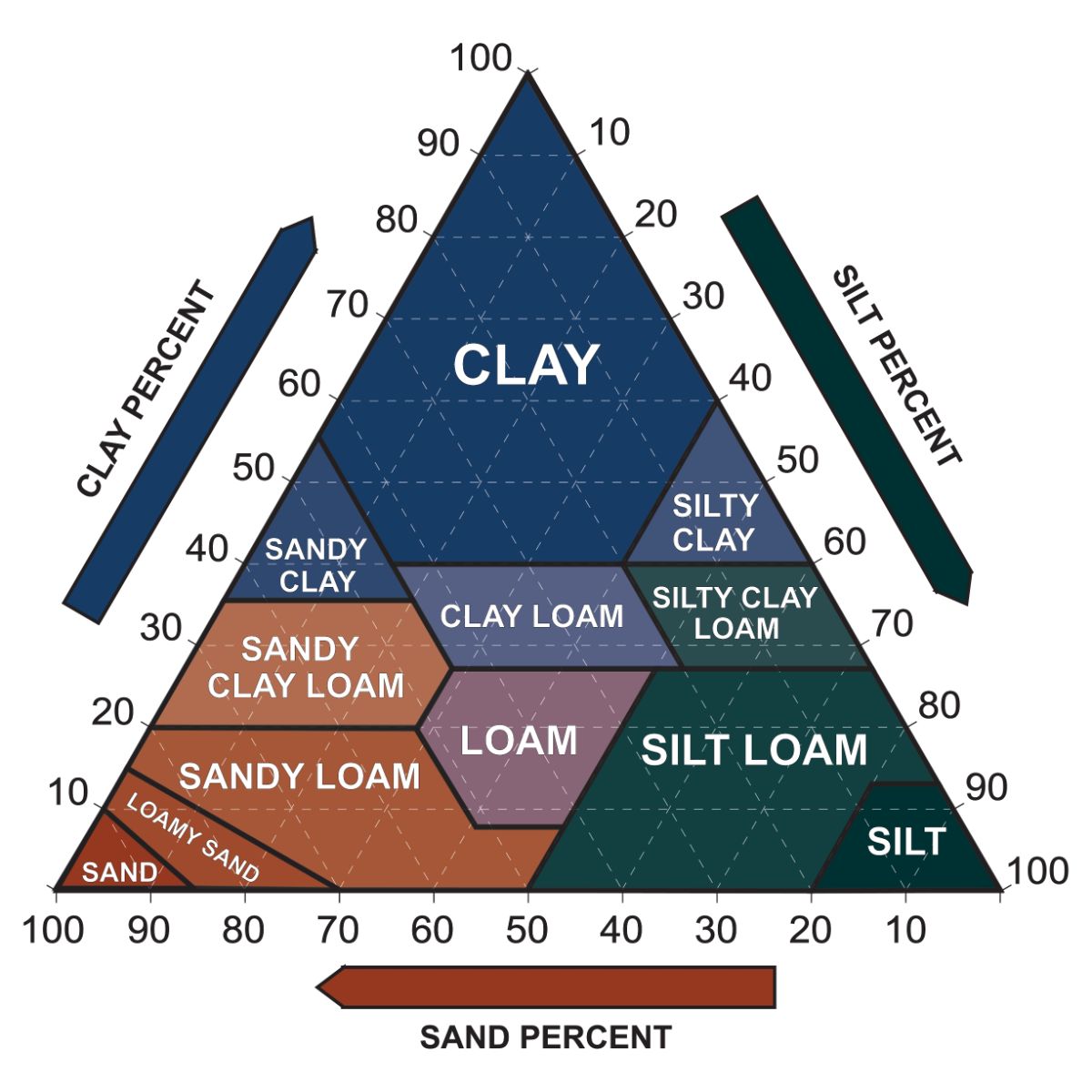

Often confused with soil structure, texture is the size of the particles in the soil.

Soil texture is commonly broken into three main categories: sand, silt, and clay. These main category sizes are usually found mixed together, as few soils are purely one or the other. Your soil might be categorized as a silty clay or a sandy clay. If you are lucky, you have loam, that beautiful mix of all the types that most gardeners wish they had.

A rough estimate of the percentage of sand, silt, and clay in your soil can be estimated with a glass jar.

- Fill the jar about a third full with soil from your garden.

- Add a squirt of liquid dish soap; about a tablespoon.

- Fill the jar ¾ full of water.

- Put the lid on tightly and shake it vigorously for a couple of minutes. Give yourself a workout.

- Let it sit overnight undisturbed.

The sand will settle out at the bottom, the silt in the middle, and the clay particles will settle out higher up. Organic material will make a loose layer at the top, and some will float.

Measure and do the math if you want to estimate the percentages, but for me, eyeballing it is good enough to tell me about what sort of soil I have.

Your soil’s texture will point to what actions to take if it isn’t where you’d like it to be. A large amount of sand, for example, will need heavy applications of organic material to bring up the water and nutrient holding capacity of the soil.

Soil Structure

Soil structure is the arrangement of those silt, sand, or clay particles. Individual soil particles are bound or glued together by the slime from bacteria and the hyphae of fungi, and in some cases, compaction.

Particle groupings, called peds, can be tiny soil aggregates like pebbles, platey layers, or even blocks. The home gardener’s interest is mostly limited to how the soil structure provides or doesn’t provide space for air and water circulation in the root zone.

Plants need air in the soil for root respiration, and many of the microorganisms need oxygen as well. Soil that is heavily compacted and has lost its structure is difficult to garden with, as the air and water roots need cannot easily reach the plant. This is one of the most common issues with gardens created out of yards.

Soil organic matter

This is basically all the stuff in your soil that is or used to be alive. Plant residues, live and dead microorganisms, fungi, a decomposing field mouse or gopher all make up soil organic matter. This is the good stuff.

Soil organic matter can further be broken down into two categories, both of which are important.

Active

Active soil organic matter is all of the still-living plus all the recently dead plants, residues, and organisms. This is the microbe food that will be broken down into nutrients for your plants. The compost that you make in your compost bin is mostly active soil organic matter.

Humus

Sometimes called passive soil organic matter, this is made of materials that were resistant to decomposition for some reason. Some of it is a thousand years old or more. Humus aids a soil in maintaining that spongy, aerated texture that we want, and is great at holding water and plant nutrients in place.

Let’s Build the Soil!

So we know we need to encourage our microbial partners, and we want to work on our soil structure. The process takes time–in fact, it is a never-ending work–but results can be fairly quick and dramatic if the soil was in poor condition to start with. We need to build the soil food web.

These tactics will work in traditional gardens and raised bed gardens. Even container gardens can benefit from some soil food web love.

Cover crops and green manure

A cover crop is basically anything that you grow on your garden or plot with the intention that it be food for the soil and not a crop that is harvested.

The benefits of cover cropping are many, but among the most important for the home gardener are the introduction of plant residue to the soil and weed suppression.

A good cover crop will do both, keeping the site captured so it does not go to weeds, and providing a nice fat amount of crop residue to be digested and turned into slow-release nitrogen and other plant nutrients. Eventually, as the microbes finish their dinner, what is left will become humus, further enhancing the soil texture and fertility.

More information on this easy but excellent practice can be found at the Organic Growers School.

Home gardeners typically use the short-term green manure method. We want to be able to use our garden bed again the next year and may not have the luxury of enough space to donate an entire growing season to a long-term cover crop. Green manure is meant to be grown only a short time and then incorporated into the soil.

Common cover crops for the home garden include buckwheat and peas. Buckwheat is excellent at reaching deep into the soil and bringing up minerals that would be otherwise out of reach for many annual plants. It also establishes quickly and is very effective at suppressing weeds.

Many types of peas are also used as green manure, to be incorporated into the soil before setting seed. Peas are legumes, and have the ability to “fix” nitrogen from the air into the soil in a usable form to other plants.

Regardless of the type of cover crop used, the crop is killed by cutting it off or by frost, and then worked into the soil by nature or by the gardener.

Compost

No discussion of healthy garden soil would be complete without talking about compost. In our modern gardening world of chemical solutions from brightly colored plastic bags, compost does what those bright colored powders and liquids cannot; provides a natural and long-term improvement to the soil.

The decayed and decaying plant and microbial residues that make up that gorgeous, coffee-ground colored compost are filled with tiny pockets and particles that carry electrical charges.

Compost and humus particles have electrical charges that attract mineral nutrients (cations) and hold them there where they will be available for plant absorption, instead of leaching away.

Equally important, the pockets provide a place for water to form capillary attachments–and so be available to plants longer. These tiny voids also aid in providing aeration in the soil, improving the structure.

Books are written about the beneficial effects of adding compost to the soil. Compost can even be added to your container garden soil to aid in nutrient availability and water retention.

If you could only do one thing to restore your soil health, add compost. Every year. Lots of it.

Mulch

Not all mulches are the same. Plastic mulch used in weed suppression by commercial growers is very effective at that task but does not contribute to soil health. The chipped-up brush and logs dyed bright colors and sold as mulch in bags at the garden center are mostly decorative.

Soil-building mulch is sort of like composting directly under your plants, with the benefit of temperature and moisture control and weed suppression.

For years I was forced to garden in an area with such poor drainage that I was limited to only raised beds. Without this sort of mulch, I could never keep the weeds down nor the moisture level appropriate.

The soil I filled the beds with was less than ideal as well. After a couple years of continuous mulching, it was dark brown and earthy-smelling, and my plants were lush, green, and happy. Then I moved and had to start all over.

One of my favorite mulches to use is grass clippings. They are free for the gathering, easy to apply, and very effective.

I have found that if the clippings are allowed to dry for a day in the sun before application, they do not mat or mold. I put them on several inches thick and reapply as necessary.

Straw, weed-free hay, dried leaves (chopped up is best), or a mix of all will work well. You know it is working to build the soil when you see you need to reapply the mulch partway through the summer. It has decayed away and provided food for your soil creatures.

Compost Tea

Compost tea is an excellent way to give your soil a boost of microbes. Because these beneficial microbes are aerobic, the process is a little different than making a straight-up compost or manure tea.

Actively aerated compost tea (AACT) is a compost tea that is, well, actively aerated to keep oxygen levels high so the aerobic bacteria can flourish.

AACT Brewers are available to purchase, but you can make your own with a five-gallon pail, an aquarium air pump, and a couple of feet of old ¼” soaker hose.

Brew time with a homemade system is about 24-36 hours. It should be coffee brown in color and have a healthy, earthy smell.

Apply the tea within a short time of turning off the air pump, or the aerobic bacteria will use all the oxygen in the tea and their numbers will dwindle.

Use it as a soil drench and apply with a watering can or garden hose sprayer attachment. Your container-grown plants will appreciate this microbe boost as well.

If making AACT interests you, I recommend an excellent book, Teaming With Microbes by Lowenfels and Lewis. There is an entire chapter on making AACT as well as many other great topics.

Park your rototiller

I can hear it now. The cries of “how will I get all this stuff into the soil?”

Okay, rototillers can have their limited uses. Starting a new garden from scratch in challenging conditions comes to mind. But for the purposes of this project, building healthier soil, they are not needed as often, if ever.

A freshly tilled garden seems loose and fluffy and satisfying–I know, I have done it myself many times–but the reality is that appearances are deceiving. Damage is being done when tilling a bed every year, or multiple times a year.

Problems with rototilling

- Soil compaction

- We’re trying to loosen and aerate our soil, and while it seems that is what the tiller is doing, the hammering action of the tines is breaking apart soil aggregates and destroying all the aeration and water transport channels your plants need.

- Near the max depth of the tines, a hardpan layer can develop from repeated impacts, causing problems with drainage, rooting depth, and nutrient transport.

- Tilled soil re-compacts very easily because the soil structure has been destroyed. Look at how hard the footprints are that you left behind you.

- More weeds

- There is a bank of weed seeds from years past just waiting in the soil for the right conditions to sprout.

- As part of their survival adaptation, many weed seeds remain dormant but viable for years.

- Bringing those seeds to the surface and exposing them to air and light can wake them up and cause them to sprout by the thousands.

- Disrupting the living organisms in the soil

- A healthy microbial, fungal, and animal population that breaks down organic residues, distributes them, and aids in plant nutrient uptake is what we are after.

- The violent upheaval and disruption of rototilling can break that cycle, and result in lifeless, sterile soil.

- Bacteria that need to be near the surface are buried, and bacteria that need to be a few inches down are tossed up to the top.

- Fungal hyphae are chopped up and the larger soil organisms like arthropods are smashed and killed.

- It may look fluffy and inviting, but tilling soil can disrupt or stop crucial processes from functioning effectively.

Alternatives to tilling

So all this green manure, compost, mulch, and other good stuff sometimes needs a way to get down into the soil. If applied in the fall, much of it will be incorporated by weather, worms, and the like by spring. But sometimes, we need to take a little action to speed up the process. We are, after all, impatient humans.

The Broadfork

A large human-powered tool, a broadfork has two long handles connected to a metal frame that has four to six large, stout wedge-shaped tines. The tines vary by model and are usually about a foot long.

To use one, hold onto the handles, step on the top of the metal frame, and wiggle it down into the soil. The handles are then pulled back, levering the tines up and forward through the soil.

Passage of these tines loosens and aerates the soil, and can incorporate some organic matter into the soil without destroying the natural soil structure we are trying to create. Things are stirred and mixed without the total destruction of a tiller.

A high-quality broadfork will run you a couple of hundred dollars, but should last you a lifetime.

Using a broadfork to work a large piece of the garden may seem like it would be back-breaking work, but it isn’t. Unlike a shovel which requires bending and lifting, a broadfork is designed to use your body weight and leverage.

Continue Your Efforts

Soil isn’t built overnight, or even in one season. It can, however, be much restored in a season or two of regenerative practices.

Creating the environment for the living components of your soil to work and thrive will go a long way toward building the health and productivity of your soil. Your plants will shrug off disease, less fertilizer will be needed, and even less weeding. Who can say no to that?

Use your tiller sparingly, use your broadfork often. Compost is your friend, as is mulch. Incorporate practices that encourage the soil food web that exists beneath the surface.

As time goes by, your tomatoes will be tastier, your carrots sweeter, and your flowers brighter.

Maggie

What about horse manure for your garden beds? How do I incorporate that and when would it be actually ready for the garden and how do I make it ready?

Mary Ward

Different sources say different things about horse manure. It is a borderline cool/hot manure, so some feel comfortable using it fresh while others would only use it after aging for a minimum of three to six months. If you do apply it fresh, I personally would spread it over the soil a few weeks before planting and then till it in so that it breaks down and doesn't just sit there in hard balls. That said, it's a really good idea to compost horse manure for six months via a hot compost process (which just means pile it up and turn the pile periodically so it breaks down evenly), and then spread it or use it as a top dressing when it is broken down and more soil-like. One of the biggest reasons to compost horse manure before applying it is weed control. Weed seeds can pass right through a horse's digestive system and then sprout when it's back out in your garden soil. A hot compost process will kill the seed in the horse manure.

I do recall an old uncle coming up to our farm every year to get five-gallon pails of manure that he mulched his rhubarb patch with in the fall. It helped mulch and protect the roots as it broke down over winter and fertilized the plants all at once.

Rodney Bray

Nice and informative. Generally farmers do not apply tons per acre of fertilizers in a single year. Thanks